The hustle is all about the pleasure.

It used to be all about the struggle.

What’s a story hustler, you ask? It’s a phrase that came up at the spring SFAI140. Mi’Jan, who spoke of love that night, also spoke of being a story hustler. The word hustler, however you want to cast it, typically conjures questionable intent, shady means for shady ends. It can refer to making money on and off the books, working in formal and informal economies. On the streets a hustler sells; sometimes there is a measure of gambling or even drugs. A hustler, to put it succinctly, is resourceful within certain circumstances.

But increasingly, in my view, the hustle refers to a different and perhaps other kind of work. It’s less about selling things, whatever that “thing” might be, and more about a new way of interacting with others amidst discord, alienation, and institutional inequity. Many women I know, women of color especially, hustle and hustle hard. Here, the hustle is about carving out new lines of labor across multiple creative disciplines in an attempt to tackle today’s social ills. It’s a degree of resourcefulness or “coming in the back door” that is often necessary in “community-building for equity.” This labor, as Mi’Jan Celie Tho-Biaz pointed out, can only really be described as hybrid. You see, Mi’Jan is a hybrid worker, one who has a lot of different projects brewing on a lot of different burners. Sometimes the heat is turned up a bit more on one of those flames but not for long. To hustle, then, is to keep all these projects going.

But let’s get back to the story part. In the past months, I’ve had the chance to spend time with Mi’Jan, whom I met through a mutual friend. In Santa Fe, meeting like-minded, woke women of color is electric, an incitement for thinking about our role in a community that is both culturally rich yet also divided. It’s undeniable that the richness and the divisions are equally worth mining. They are the stuff of experience, belonging, exclusion, inter- and intra-cultural animus, and political- and self-determination. To that end, Mi’Jan is a documentarian. In this role, she not only tells stories but elicits them from others, listening and asking questions of students, educators, women of color in nonprofits, indigenous artists, black documentarians, and juvenile offenders, to name only a few. Her work takes her to university campuses, where she gives educational talks, as well as philanthropic and nonprofit organizations, detention centers, and artist residencies. Indeed, this edition of Meet Your Makers is about the art of storytelling. It is also about making oral histories matter.

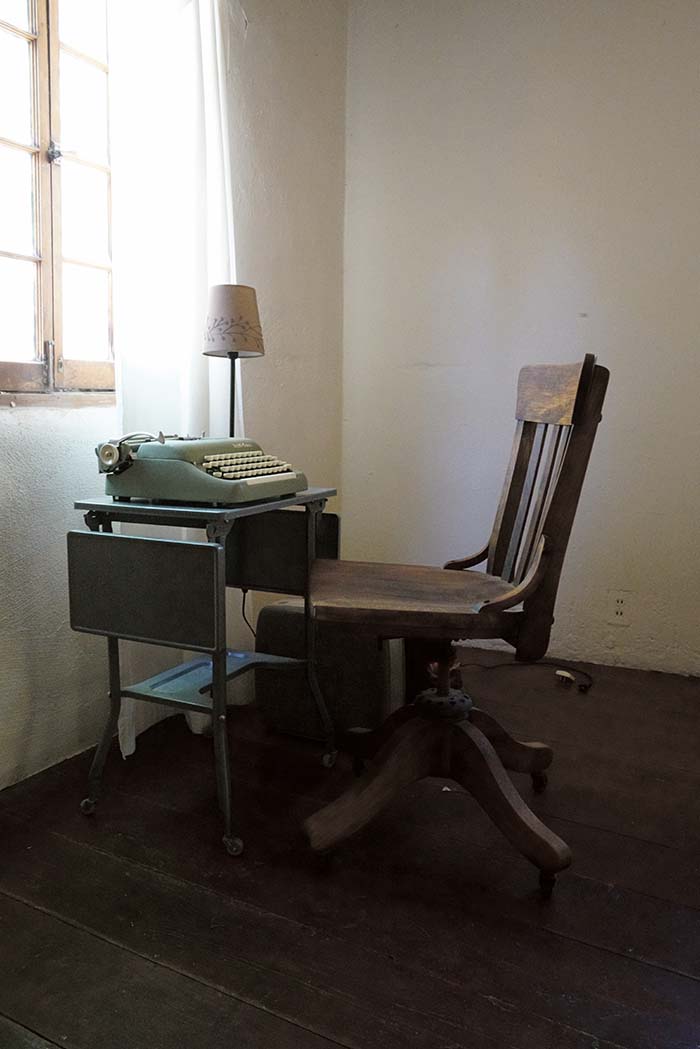

“What are the tools of the trade?” I asked. How, in other words, does one even begin to embark on “testimonial collection”? I realized this question seemed simplistic or maybe too diffuse, given the universal proclivity for stringing together component events into a meaningful whole, a story of sorts. Doesn’t everyone tell stories? Given Mi’Jan’s graduate background—she has a doctorate in International and Multicultural Education from the University of San Francisco—it’s clear that there is both an ethical and a research component to this line of cultural work. There are protocols for story gathering; there are also, significantly, informal covenants that Mi’Jan makes with the people to whom she listens, as well as to herself. As our conversation spun around, a list began to take form. To say “list” might seem heavy handed; we all know that sometimes stories take us to psychic and real places that are surprising, sad, or even overwhelming, places where a list might not make sense. That said, wresting and documenting testimonies is by no means formulaic. But with my own notebook and recorder out on the table, I began to trace the lines of Mi’Jan’s story practice. What lies ahead is a schema of her method for amplifying the voices of those who have seen and experienced oppression, injustice, and trauma, as well as amplifying those voices that speak of rebuilding, overcoming, and self-reflection.

(1) Ask yourself: Whose stories are being collected?

Whom, in other words, “are you generating the story with?” Mi’Jan’s wording was thoughtful, measured even. The story, in this line of thought, is like an organism that transforms when uttered. To speak a story is to generate it anew for the benefit of another, with another. But who are the participants, and what is the context? If you’re talking to women of color working in non-profits, as was the case for a recent Women of Color Leadership Initiative with the Santa Fe Community Foundation, then what are their needs? What kinds of isolation do they feel in their line of work that can be eased through gathering with like-minded individuals? How is this professional isolation different from the kind of isolation experienced by female juvenile offenders, who, in Mi’Jan’s experience with the Voces de Libertad poetry program through the Santa Fe County Youth Development Program, are acutely attuned to the sounds and yearnings of the “outside”? Their poetry speaks of confinement, regret, and, yes, love. Isolation means different things, according to whom you’re asking.

(2) Establish a rapport.

Some time ago, when HIV testing took over an hour (now it takes less than five minutes), Mi’Jan sat with and interviewed those who had come in to have their saliva tested. This was before she became a documentarian. She was a public health worker then, in an environment where spending time with people in traumatic or troubled circumstances was her norm. What came out of that experience was the importance of establishing a bond in a safe space to encourage clients with the ability to speak. This is true in her story practice. “If it takes a long time or a dedicated time to establish a relationship with the narrator, then that’s what I have to do.” This approach differs from journalism to the extent that the deadline isn’t what drives the relationship between her and the narrators. It’s about building trust, which “is especially important in marginalized communities,” where social bonds, whether between families or governmental entities, are constantly broken or in flux. Bringing a true and genuine sense of curiosity to the table is part of that bond.

(3) Integrate a real-time component.

This year, Mi’Jan has been thedocumentarian in residence at IAIA. Her role has been to hold sessions where students learn to collect oral histories. This work has included teaching everything from making sure the recorder is working to rotating interviews—for the benefit of learning the ropes—between various groups. First, professors were interviewed, then the students themselves, then 2016 artist-in-residence Cannupa Hanska Luger, and finally Mi’Jan. Each group made up the other’s “live audience.” While the interview was audio and video recorded, there was a real-time component:

Oral history as a discipline usually says we’re collecting these stories and they’re going to be archived in a repository. Because I was trained by a publisher (McSweeney’s Publishing, a non-profit owned by Dave Eggers), their whole practice is to amplify. Their belief is, “if we’re collecting stories of human rights crises and issues, it does the greatest good when the widest audience is reached and helped in action.” I put that front and center when I talk to people about my story practice, because that’s my belief, too. I’m working in marginalized communities, and it’s a bit disingenuous to collect their stories, and their emotional labor, and their time, and their energy, all this rich work [so] that maybe five people, who are of a privileged professional group or a social sector, will have access. If it’ll only reach five people in an archive, that’s not a good pairing.

(4) “Hold the Tiger’s Tail.”

“It’s good to have four or five anchor questions floating around in your head if you need to defer.” Sometimes, however, your questions can only lead so far; in fact, those anchors aren’t the real engines of story gathering. Rather, it’s keeping up with the narrator—that’s what moves a story forward. “You should be riffing and following that thread, the thread that’s presented to you by the narrator. That’s the meatiest, the most heart-centered, the most compelling; it’s like a dance.” At Voice of Witness, they call that improvisational element “holding the tiger’s tail.” And “when you get really good,” Mi’jan explained, “you become comfortable holding the tiger’s tail.” But being in the thick of it for the amount of time necessary to conjure real stories also takes a certain kind of endurance and mindfulness.

And “when you get really good,” Mi’jan explained, “you become comfortable holding the tiger’s tail.” But being in the thick of it for the amount of time necessary to conjure real stories also takes a certain kind of endurance and mindfulness.

“It’s a practice,” in which completely listening and “living in the questions . . . is just like meditation.” This is even more so the case when moments of “productive discomfort” surface, because sometimes being vulnerable enough to tell your story, or listen to the stories of others, draws out both pleasure and pain—and the whole spectrum of emotions. Pushing boundaries, while eliciting discomfort, can be generative, as Mi’Jan wrote in reflection for her work with the Rockefeller Foundation:

During the fall of 2016, I attended an artist talk given by Bear Witness, from the music group A Tribe Called Red, while we both engaged in our respective residencies at the Banff Centre. Bear Witness remarked that art has the capacity to push boundaries on every level, and can do so in the most respectful and responsible ways. At first pass, this idea seemed counterintuitive. Pushing boundaries can be uncomfortable, risky work, often met with resistance. As I replayed Witness’ statement in my mind during the window of days that ebbed from the Banff Centre’s Truth and Reconciliation summit, into the United States’ presidential election, I realized that I had unconsciously equated discomfort with disrespect.

(5) Bring “the whole self forward.”

Currently, Mi’Jan is prototyping a new story-gathering series based upon a recently completed residency at Detroit’s Burnside Farm. It’s about creating unusual pairings between cultural workers and local chefs for storytelling experiences that might not otherwise take form. In her design for the event, a theme characterizes each course and serves as a point of departure for a new story. Over dessert, for example, participants will share their stories of pleasure. While it’s easy to make pleasure synonymous with sex, pleasurable experiences can include eating good food, listening to music, walking, spending time with loved ones, anything that centers on one’s emotional, mental, and physical wellbeing.

The notion of wellness, of bringing the whole self forward during the creative process, has occupied Mi’Jan for some time, especially in her thinking about the nature of activism. Angela Davis’s visit to New Mexico for her Lannan Foundation talk was a flashpoint. Over dinner, Davis spoke about how Black Lives Matter activists emphasized self-care, more so than earlier justice-centered movements like the Black Panthers. Amidst the gritty, oft-violent, and thankless task of laboring for equity, focusing on individual wellness held the potential to bolster a movement’s sustainability over the long term. This came from Davis, who has experienced all sides of activism. Mi’Jan has gotten some push-back on her own ideas about integrating pleasure and wellbeing into social justice, but she believes that doing so “feeds organizing and activism.”

The story-gathering series will travel to other sites, including Miami, Hawaii, Providence, New Orleans, Jamaica, and Havana.

Testimonial Now

We’ve just seen the dismantling of confederate monuments in New Orleans, a testament to the fact that history is constantly contested and under revision. In this revisionary era, a time when even “fake news” gets attention, what role does oral testimony play? What are words to artifacts and “hard” evidence? And how do individual voices give dimension to the events that mark our collective and personal pasts, presents, and futures? When you talk to Mi’Jan, storytelling is life, and to those voices that are often silenced, sharing stories is valuable, necessary, affirmative, and political. Being able to witness, participate in, and bear forth testimony is a kind of cultural work toward a more just nation. To have a story practice is “juicy and life affirming”; it is also a way of bringing communities together for positive social change. That includes work on the ground with other socially minded creatives, for instance, convening Black and Indigenous documentarians through the Omega Institute in Rhinebeck, New York—or in the realm of academia, as a scholar in residence at Columbia University in the fall and spring semesters. While her home base will remain Santa Fe, the hustle constantly takes her elsewhere, only to bring her back again.

My name is Mi’Jan Celie Tho-Biaz, Story Hustler.

Recently, Rose and Roxanne asked me, “Mi’Jan, what’s your love story?”

I was flustered in that moment, but I can tell you now that it is bound by two names.

My sister is a Brave Heart.

And Mi’Jan means: My Soul, My Love.

Allow me to back up, though, just a moment, to the heartache of 2016.

Watching:

—Black bodies be murdered, live.

—My father’s debilitating illness.

—And the 10 deaths of my family, friends and colleagues.

On top of that, Shawna, my best friend in the whole wide world, also experienced her own loss and moved out of state.

Miraculously, though, at the same moment, I started falling in love for the first time in years.

So confusing!

Thankfully, my daughter cleared things up.

“Hey! He just walked us 2 blocks – in the rain, with NO UMBRELLA – to our car. This guy so likes YOU! You so

like HIM! What are you going to do about it?”

Here’s a quick rundown from that first season:

Be vulnerable.

Instigate many, many breakups.

Enjoy exquisite makeups.

Love him.

And let him love me.

In other words, it was a hot mess, and I showed up to my story gig work, asking:

What are we writing today?

LOVE

Are you kidding me?!!!!!

They’re incarcerated and facing precarious futures.

Why write about love?!!!!!!

I will always remember one writer’s answer, though. The one with the bloodied knuckles, track marks and tattoos,

saying, “Mi’Jan, we all crave love.”

So, when Omega Institute asked me for a proposal, I wrote them a love letter prayer for these times.

To convene 20 Black and Indigenous Social Movement Documentarians.

Fast forward:

Omega said “yes,” and now I say “may all of these Love Letter Prayers be true.”

Mi’Jan Celie Tho-Biaz, “Love Letter Prayer in Drag,” Santa Fe Art Institute, March 24, 2017. Courtesy of Mi’Jan Celie Tho-Biaz.