The Gift, a creative and scientific immersive art installation at Colorado College, considers diverse social, cultural, and ethical perspectives in science.

The human experience isn’t much different than that of the sky.

“One of our main goals is helping others understand that we are all changed by those around us,” says Colorado College astrophysics professor Natalie Gosnell, co-creator of The Gift, an immersive art experience that tells the story of two stars, one at the end of its life. “Then we can understand and frame those changes with care and compassion if we choose to.”

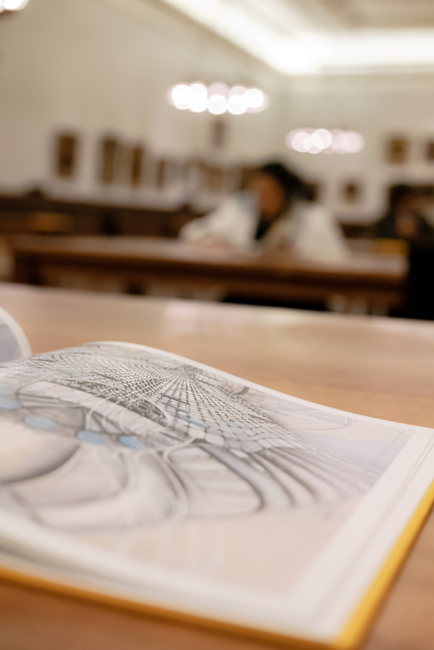

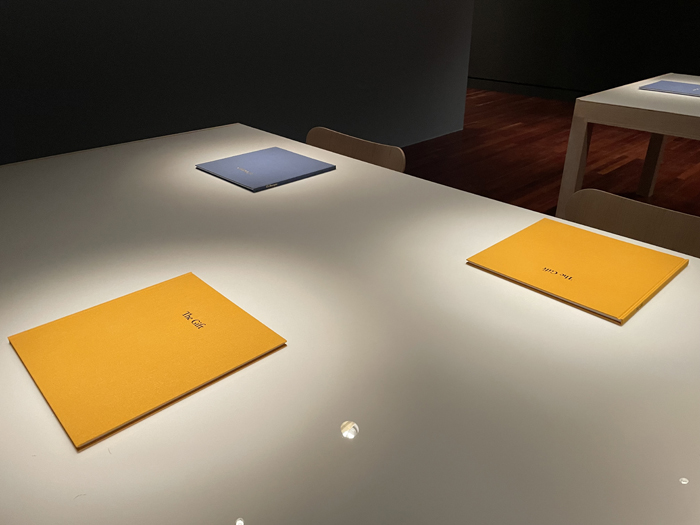

In The Gift, the creators explain the phenomenon of two stars being so close together that from Earth, they appear as a single point of light. But a closer look reveals that the two stars are so intertwined that the star at the end of its life actually transfers its material to the other star. The collaborative project—which opened March 3, 2023, and continues through June 18, 2023, at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center at Colorado College—combines art, storytelling, and music with Gosnell’s contemporary astrophysics research as a backdrop.

Gosnell worked with artists Janani Balasubramanian and Andrew Kircher, director of public humanities at the Bard Graduate Center Gallery in New York, to create an experience that they agree “heeds the call of anthropologist Emily Martin” to “wake the sleeping metaphors of science.”

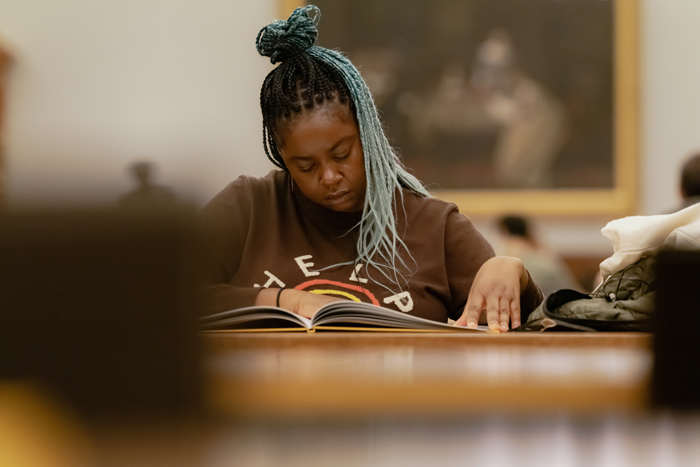

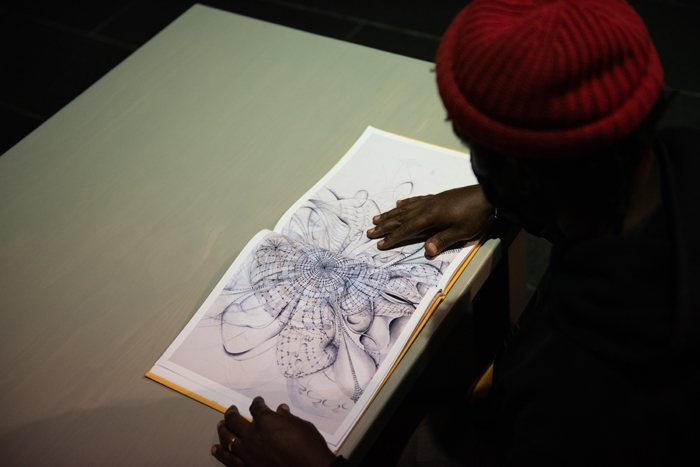

Guests file into a space to read the story and while having their own unique experience with the book and musical score, others around them are, too. One of the themes of the project—that the collective and the individual meld together—is suddenly alive.

“I think that also is mirrored in the juxtaposition of the different components of the piece—we have this book with the words that are co-written by me and Janani interspersed with excerpts of artwork by visual artist Amy Myers,” Gosnell says. “Then the book itself is designed by Katie Hodge. And then this exists in a space that is filled with music composed by Tina-Hanaé Miller. And so all of us offered our own interpretation of the story. But then all of these different pieces get layered together, and you get these wonderful moments of serendipity and how they all went up with one another.”

The project is also a stark reminder that two worlds colliding—creativity and science—can have a powerful outcome. Astrophysicists aren’t often considered artists, but Gosnell and Balasubramanian both find solace in the space where the two disciplines meet.

“In astrophysics, particularly, we have to be storytellers. Because we don’t get to hold the things that we study, we’re taking pieces of information from telescopes and from computer models, and trying to craft a story of some astrophysical phenomenon or object that we studied,” Gosnell explains. “I sometimes tell people I’m a star detective, taking small pieces of information and trying to figure out the history of something. And in figuring out that history, I have to use all of my understanding and knowledge of physics to sometimes connect the pieces of information I have.”

For Balasubramanian, the connection between art and science is as old as time.

“One fact that I tell my students when I teach is that in the Greek system of Muses, astronomy had her own muse: Urania. She was the muse of astronomy. Astronomy, in that period, is among the creative pursuits. I think it’s important to recontextualize this work in that long lineage.”

The project, which debuted in New York in 2021, received funding and support from the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, the Public Theater, New York Community Trust, the Sundance Institute, the Guild of Future Architects, Map Fund, Stanford University, Brooklyn College, Creativity and Innovation at Colorado College, the University of Colorado, and the Tow Foundation.

The Colorado College installation represents a way in which the three co-creators say art can be a familiar space for those who maybe find the world of astrophysics, or science in general, intimidating or uncomfortable—or vice versa.

“This space between art and science, I think, is more inviting, because we’re sort of relieved of all of the expectations of either art or science,” Gosnell says. “And so we are able to step into a new space and make our own rules, or lack of rules around who was invited into those conversations, and what does it mean to create new things in this art science space.”

As a professor, this rings especially true for Gosnell. In 2019, the American Institute of Physics reported that only 11 percent of bachelor’s degrees earned in physics and astronomy went to Latinx students, and only 3 percent went to Black and African American students. In the same year, only 19 percent of PhD students in physics were women.

“So we have these stories written not by a diverse group of people,” Gosnell says. “We are intentionally choosing to walk a different path, going against the prevalence of options or examples that have been coming beforehand.”

Another study from 2020 that focuses on the representation of African American students in undergraduate physics programs found that students would have a greater chance of success if there was a heightened sense of belonging in the field, “so it’s not about creating a more rigorous curriculum. It’s not about math preparation. It’s about acknowledging the humanity of our students, creating community and belongingness,” Gosnell says. “And I think how we tell our science stories is one small part of this larger goal that we need to create more inviting, welcoming spaces for our students, because our students are going to become the next generation of scientists.”

Balasubramanian said they believe a lot of people have a false idea that science is a closed and objective conversation—which is what The Gift takes head-on.

“It’s definitely not. It’s something like any other kind of knowledge practice that is created by people that is impacted by our social and cultural circumstances,” they explained. “And as such, it’s important to bring social/cultural/ethical perspectives into scientific thinking and scientific communication.”