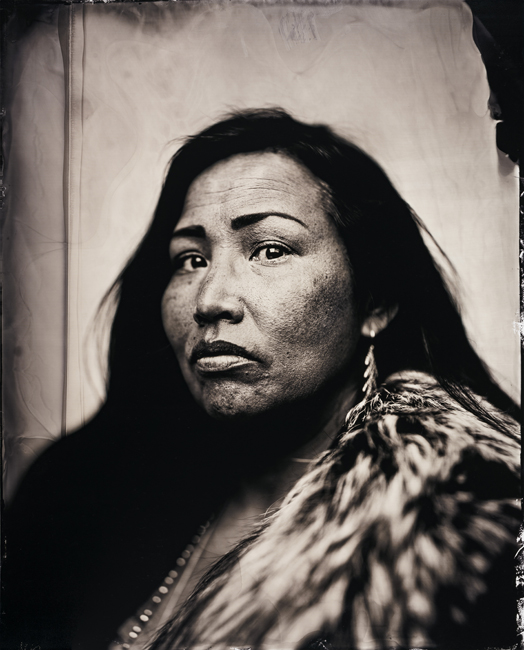

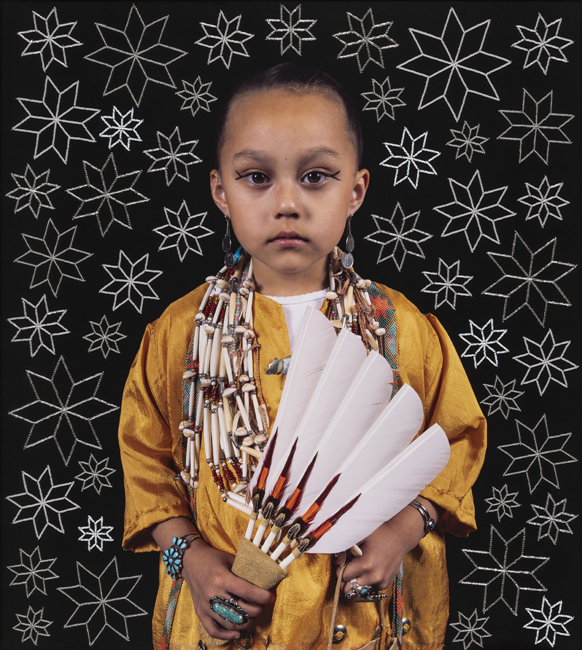

Speaking with Light: Contemporary Indigenous Photography, a first-of-its-kind retrospective now at the Denver Art Museum, celebrates Native culture while confronting settler colonialism.

DENVER—The first major retrospective of Indigenous photography arrived at the Denver Art Museum this month, showcasing artists from more than fifty nations and images that challenge visitors to rethink narratives about Indigenous life and how it’s woven into culture, even today.

Speaking with Light: Contemporary Indigenous Photography spans the past three decades with more than seventy images, videos, and multi-dimensional works that emphasize historically underrepresented views through the lenses of artists who are most equipped to tell their own culture’s stories. The exhibition, which debuted at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth, Texas, is curated by John Rohrbach, curator of photographs at Amon Carter, and Will Wilson, a Diné artist and curator. Denver is the show’s second stop.

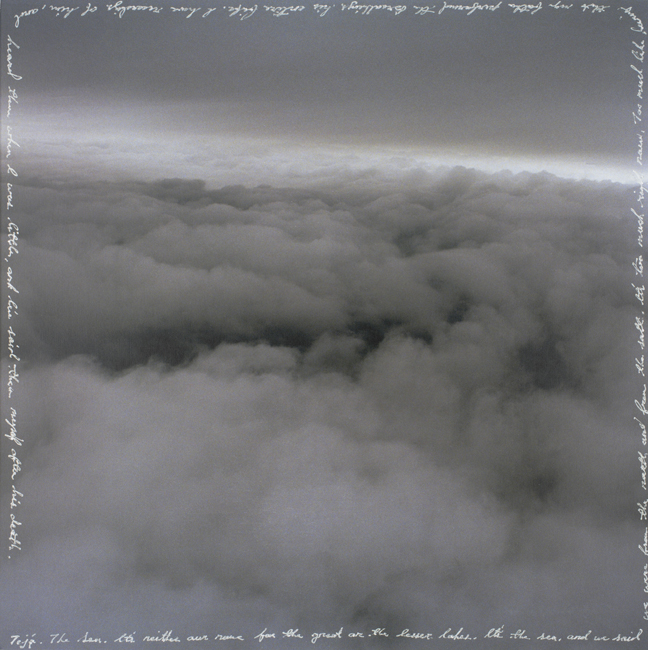

“In general, a lot of Indigenous photography and Indigenous art has to do with time and the understanding that for many Indigenous people, past, present, and future are not distinct,” says Eric Paddock, curator of photography at the DAM and the local curator of the exhibition. “They all occur together at the same time, and also there’s a greater awareness and connection with nature and with the natural world.”

Among the images is photographer Zig Jackson’s Indian Man on the Bus, made in San Francisco in 1994. Jackson (Mandan/Hidatsa/Arikara), the first Indigenous photographer to be awarded a Guggenheim, blends time, culture, and the rich complexities of modern Indigenous life. Like the exhibition itself, the image is meant to highlight a dichotomy of culture and power.

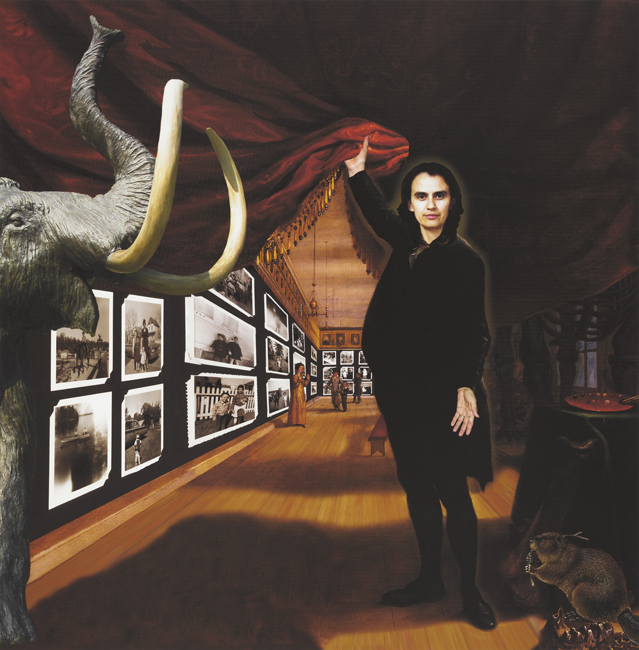

Speaking with Light begins with a gallery of images by non-Native photographers, many of whom were white, when Indigenous leaders traveled to meet with lawmakers for treaty negotiations in Washington, D.C., and Ottawa, Canada, in the 19th century.

“I think we know how a lot of those treaties turned out. But part of the ritual of holding these negotiations and these meetings was taking the leaders of Indigenous communities to photographers’ studios to have their pictures made,” Paddock explains. “And those photographs formed, I think, some of the foundation of what white America believes about Indigenous people.”

As visitors wander further through the exhibition, they’re met with three more galleries that spotlight artists and their use of storytelling, some engaging in humor, such as Jackson’s photograph. Others delve into identity and connections to the natural world, like Cara Romero’s Water Memory, which features two corn dancers completely submerged in water. Romero (Chemehuevi) told the New York Times last year the image “was inspired by a catastrophic event in Native history: the construction, in the late 1930s, of the Parker Dam on the Colorado River that resulted in the flooding of thousands of acres of Chemehuevi homeland in Southern California.”

Some of the pieces in the show were acquired by the DAM and loaned to the showcase, while others were produced through previous partnerships and programs of the museum. A series by Wendy Red Star (Apsáalooke) was completed while she was an artist in residence.

DAM director Christoph Heinrich said the exhibition also touches on one of the DAM’s major goals: to show more Indigenous art. In 2021, the museum opened a new building, 280,000 additional square feet of space, much of it dedicated to more inclusionary exhibitions. The Indigenous Arts of North America galleries is one of them.

Heinrich and Paddock also emphasize the museum’s mission to show more contemporary art, like Speaking with Light.

“Photography is powerful in its storytelling,” Paddock says. “These photographs trace paths across time and place and reflect experiences that can shape and inform understanding of the past, the present, and the future.”

The curators encourage continuing dialogue and understanding about Indigenous life and culture even as patrons leave the exhibition. A vestibule just outside the gallery features a station for visitors to visit the website for Indigenous Photograph, which its creators say is a “space to elevate the work of Indigenous visual storytellers and bring balance to the way we tell stories about Indigenous people and spaces.”

“It’s a way for us to extend the conversation,” Paddock says.