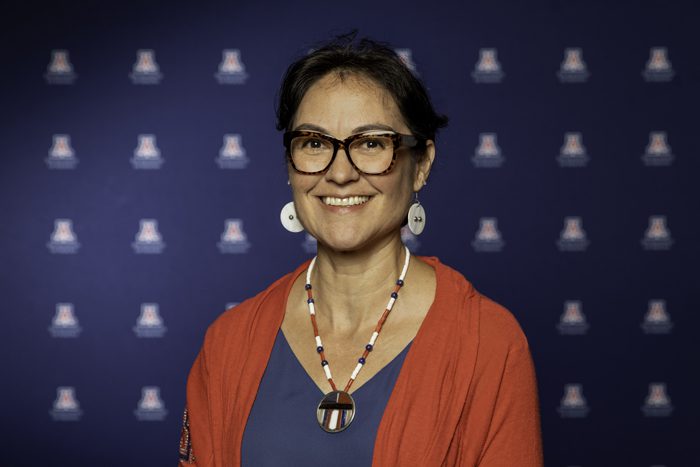

Shelly C. Lowe (Diné), the first Native American to chair the National Endowment for the Humanities, is approaching her high-profile job at the granting institution through an Indigenous lens.

ALBUQUERQUE, NM—It’s a warm and breezy Thursday evening and Shelly C. Lowe (Diné), the first Indigenous individual to lead the National Endowment for the Humanities, is wrapping up a four-day tour of New Mexico and Arizona during a media roundtable at the Albuquerque Press Club.

“It feels really good to be here in the dirt and the dust and the heat and I’m sunburned,” says Lowe, who was born in Gallup, New Mexico and raised in Ganado, Arizona on the Navajo Nation. Lowe and a caravan of Washington D.C.-based NEH staff have traveled to the Southwest to hear the stories of the region’s urban, rural, and tribal communities—and to let local humanities organizations know that there’s available financial support to tell these stories.

This is the first field trip for Lowe as the newly confirmed chair of the NEH, an independent federal agency that gives grants to cultural institutions and individuals to support research and learning in history, literature, philosophy, and other areas of the humanities, which encompasses anthropology, art, languages, and many other fields. Lowe’s top priorities include personal outreach and getting money into the hands of small organizations, tribal communities and colleges, and cultural centers.

“My vision is really simple,” says Lowe during the media event on May 19, 2022. “Why don’t we fund these smaller places?” Since its 1965 formation, NEH has given approximately $5.6 billion through more than 64,000 grants, including a project that materialized into Ken Burns’s 1990 documentary The Civil War.

Lowe, who started the job on February 14, 2022 following confirmation by president Joe Biden, has served as the executive director of the Harvard University Native American Program, assistant dean in the Yale College Dean’s Office, and director of the Native American Cultural Center at Yale University. From 2015 to 2022, she was appointed by Barack Obama as a member of the National Council on the Humanities, the twenty-six-member advisory body to NEH.

Her vision for NEH, which she’s approaching through an Indigenous framework, is partially informed by her experience as a trustee for the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian.

“A lot of conversations talked about that this is our museum as Native people,” says Lowe. “It might be our museum, but how many of our youth are going to ever step foot in this museum? Because it’s in Washington, D.C. [and] it’s too expensive. How are they even going to get here? So how can we talk about this as our museum when they’re never going to see it?

“I thought about that in terms of coming into leadership here in the NEH, and thinking about how many people out there don’t think that this is our agency, as American people,” she continues. “I’m really focused on trying to make sure that what we do reaches the populations we have not served, that we’re not just on the East Coast, we’re not just on the West Coast, we’re not just in big urban areas.”

Lowe adds that other challenges include educating people on the function and purpose of NEH as well as differentiating the organization from the National Endowment for the Arts, a sister organization that offers financial support for visual arts, dance, design, exhibitions, festivals, folk art, music, performances, theater, and more.

During her Southwest visit, Lowe learned more about an NEH-funded project at the Pueblo of Isleta that is creating an accessible digital archive to preserve tribal records and historical materials. She also met with Albuquerque’s National Hispanic Cultural Center, AfroMundo, and Keshet Dance and Center for the Arts; gallupARTS in northwestern New Mexico; and with Navajo Nation president Jonathan Nez and first lady Phefelia Nez. Lowe also spoke at her alma mater, Ganado High School, about the role of the humanities in addressing personal and societal challenges.

Along with one-on-one conversations, NEH is spreading the word about its grant opportunities via its fifty-six state humanities councils (which include American Samoa, District of Columbia, Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands). Brandon Johnson, executive director at the New Mexico Humanities Council, says that the Albuquerque-based organization provides grants as well as free trainings, such as grant-writing workshops. He hopes that future funded projects can lead to a greater understanding and celebration of the Southwest’s cultures, histories, and legacies.

“There are thousands of unrecorded, unrecognized stories in the Mountain West,” Johnson tells Southwest Contemporary. “Artifact stories that are kept close to the vest and stay part of the family story. I think the biggest factor in us being able to help those stories get out and support that work is by building relationships of trust. We’re not interested in extracting stories. We’re interested in enabling people to tell their own stories.”

Lowe, speaking with SWC following the media event, echoes Johnson’s sentiment.

“I do think that having a really good balanced outreach and balanced effort to tell stories that we haven’t heard before and create educational curriculum that is much broader and much more of a national focus is really important,” says Lowe, who is also thinking about how NEH and state humanities councils can help bridge digital connectivity limitations in rural areas. “It’s just so hard when individuals don’t have a good sense of what it’s like and how it’s different in other parts of the country.”

Lowe stresses that NEH is not a scary, unreachable behemoth based on the East Coast—“we’re a very small agency,” she says—and that grant funding, even for the tiniest of humanities organizations, is very much a reality.

“I really want them to feel like NEH is not just a possibility, but that it’s a place where they should be looking at funding opportunities and having conversations with us,” she says. “I’m really focused on how we can broaden our work, broaden our outreach, and help broaden our understanding of what we do more nationally.”