Topologies, Senga Nengudi’s retrospective currently on view at the Denver Art Museum, acts as a call-to-action: for marginalized bodies and beings to be seen in the world.

December 13, 2020–April 11, 2021

Denver Art Museum, Denver

Before exiting Topologies, Senga Nengudi’s retrospective currently on view at the Denver Art Museum, white vinyl text adhered to a black wall delivers a parting message:

“Simply by being, that’s a political statement. So, whatever comes out of me has all these elements of me in it: I’m black, I’m a woman, and at this point I’m a woman of a certain age. So simply by being, I am those things.”

The artist’s statement highlights her blackness. Her womanliness. Her age. And, importantly, her being: her presence as a black woman “of a certain age,” not just as check marks on a demographic form.

Given both our contemporary moment and American history, such an identity is political because the indicators marking Nengudi are marginal or minority positions. To occupy those positions means that one primarily works in contrast to, against, or in spite of normative power centers. While our country’s social dynamics have shifted over the sixty years since the Civil Rights Movement, those loci of power are still clear: whiteness, masculinity, and youth.

Since these identities present themselves visually, it’s no wonder that much of the practice of the Colorado-based artist, a prominent figure of the 1970s Black American avant-garde, focuses on the body. The exhibition, which contains more than seventy pieces of abstract and conceptual artworks by the internationally recognized artist, opens with documentation of her 1978 performance Masked Tape. The photographic prints demonstrate an attention to the corporeal that pervades the entirety of her forty-year career.

More recent wall sculptures, such as R.S.V.P. Reverie A or Rubber Maid, gesture toward the female form through an abstracted biomorphism. In other instances, Nengudi created wall sculptures explicitly for bodily interaction.

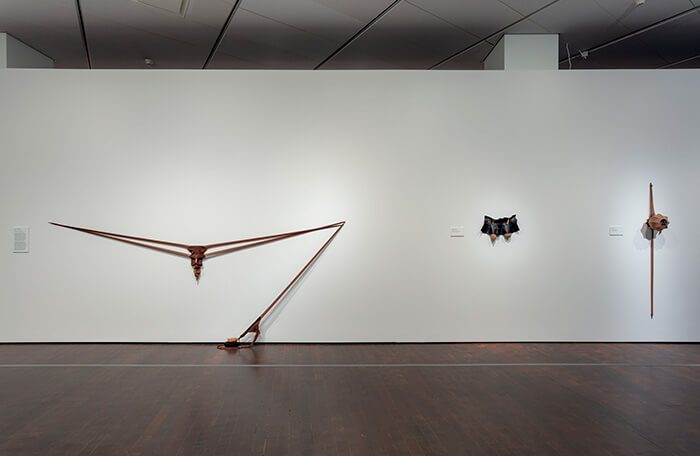

R.S.V.P. Performance Piece occupies this latter category. The artist constructed the artwork from brown, nylon pantyhose stretched in a stacked, v-shaped assemblage along the museum wall; one sand-filled appendage extrudes outward along the floor, anchoring the sculpture in place.

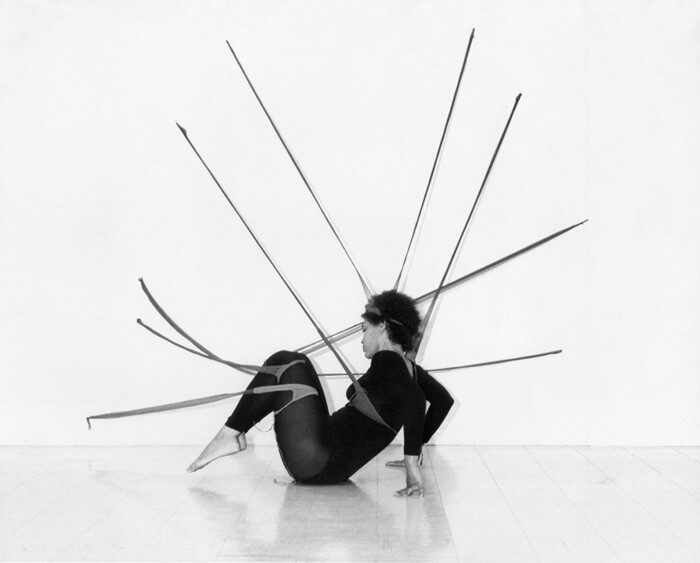

Archival photographs beside the sculpture show Maren Hassinger—Nengudi’s long-time collaborator—interlacing her legs and torso into the nylon pantyhose, pulling and stretching the material into different directions in a 1977 performance. In addition to these still images, several projections throughout the exhibition present recent iterations of R.S.V.P. Performance Piece, similar to the one in the video below:

In the clip, Hassinger stands upright, moves left and right, forward and backward. She lowers herself, then twists and reaches upward. Throughout the performance, the nylon alters and adapts to her body and its corresponding movements; simultaneously, the material constrains and dictates her range of motion. This artwork is as much kinetic as it is conceptual.

Within the context of Topologies, though, viewers encounter these sculptures primarily as material vestiges of a body formerly at work/play. While the artwork originated as an apparatus that entangled a human form in motion, the museum setting transforms it into a static object solely for observation. True, there are images and videos of Hassinger’s body interacting with R.S.V.P. Performance Piece; but the physical body has disappeared. The work’s dynamism is no longer present.

From a certain perspective, acknowledging corporeal absence is a standard institutional critique. Art museums by their very nature are static entities tasked with archiving the fetishistic remains of what we once considered art for the sake of posterity and enhancing stakeholders’ shares in the art market. The institution simply has no use or place for actual bodies or interactive works.

But absent of a human form, the sagging nylon of R.S.V.P. coupled with Nengudi’s quote on the politics of being reminds me of Ralph Ellison’s 1952 masterpiece Invisible Man. In the prologue, the unnamed narrator says:

“I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me…That invisibility to which I refer occurs because of a peculiar disposition of the eyes of those with whom I come in contact. A matter of the construction of their inner eyes, those eyes with which they look through their physical eyes upon reality.”

The narrator wasn’t a “spook like those who haunted Edgar Allan Poe,” nor was he “one of your Hollywood-movie ectoplasms. Rather, he was a black man living in America; and our country’s white populace “refuse[d] to see.” His humanity was unacknowledged, thus he disappeared. He was invisible.

Through this lens, the inert nylon of R.S.V.P. can be read as a critique of whiteness in America. A critique of misogyny in America. A critique of ageism in America. The black female body of a certain age has disappeared from R.S.V.P. Instead, we view the aesthetic remains of what a body left behind. The artifacts in Topologies challenge us to confront the inherent differences between an actual body, an actual being, and their aesthetic relics.

In the closing sentences of Invisible Man, the narrator says: “even an invisible man has a socially responsible role to play,” and that role, he concludes, is to emerge from his subterranean abode, return to the world, and tell his story to those who listen “on the lower frequencies.” Perhaps Topologies offers us something similar: a vision for those who see on different frequencies.

But displaying the artwork of a Black woman of a certain age to those who see on different frequencies is merely the starting point for a broader, more embodied movement toward a widespread realization of racial and social justice. The work of Topologies can act as a call-to-action: for marginalized bodies and beings to be seen in the world. To be heard. To be felt. To be accorded the same humanity as those located within the center. Because as the narrator of Ellison’s novel notes in his epilogue: “Without the possibility of action, all knowledge comes to one labeled ‘file and forget,’ and I can neither file nor forget.”