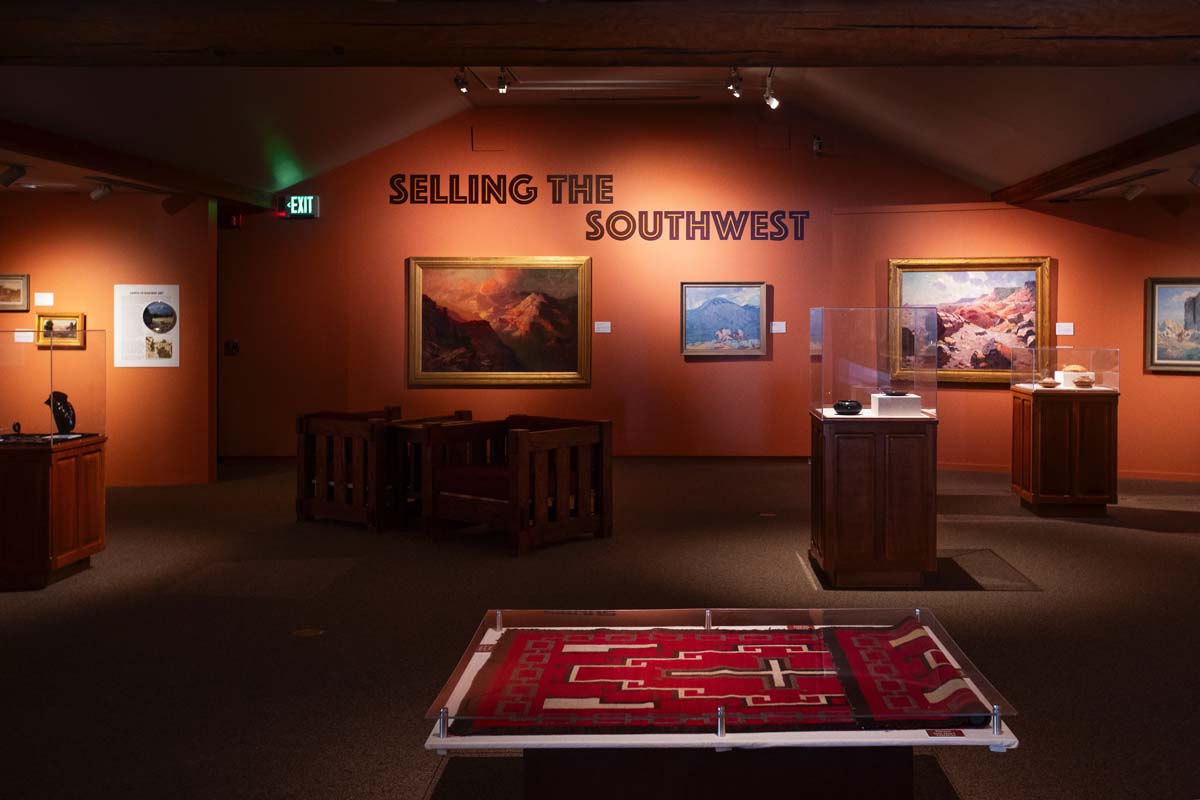

Selling the Southwest unpacks how the marketing efforts of the Santa Fe Railroad and Fred Harvey Company romanticized and exploited the artistry and culture of Indigenous people.

Selling the Southwest

January 28, 2024–January 15, 2025

Museum of Northern Arizona, Flagstaff

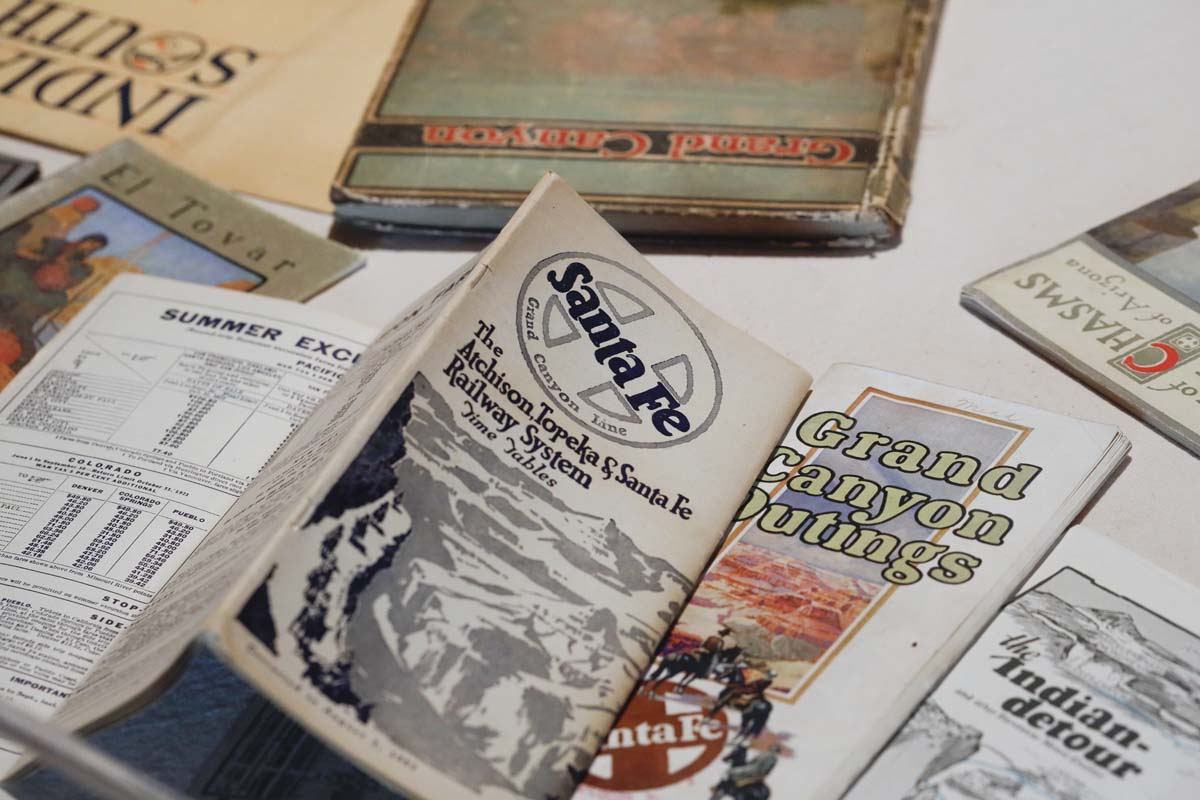

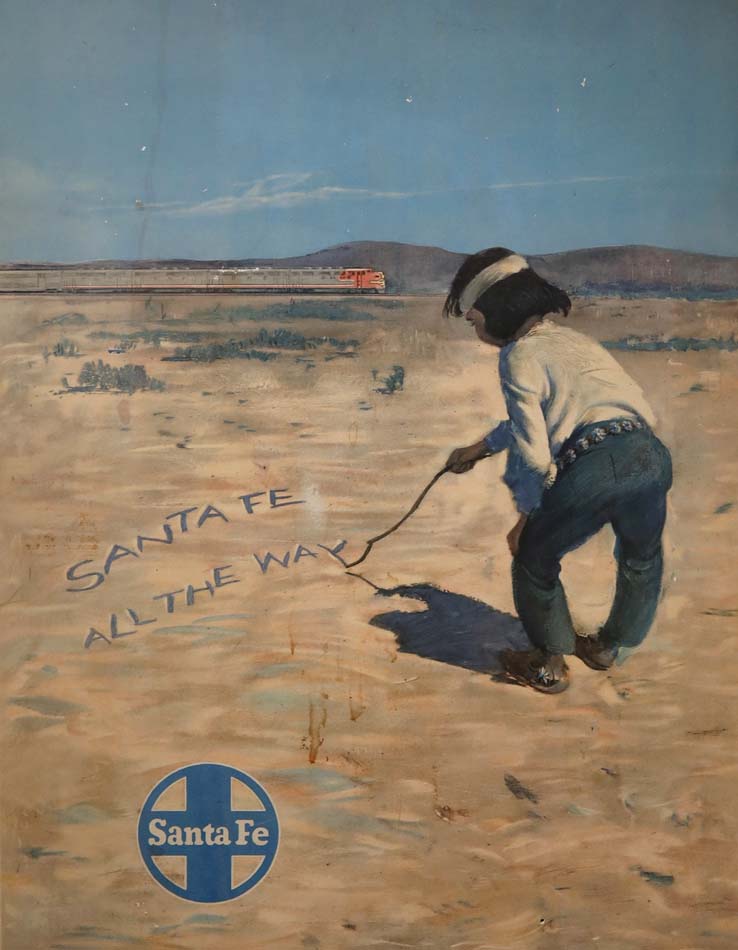

A poster created by the Santa Fe Railroad circa 1946, just inside the entrance to Selling the Southwest, an exhibition on view at the Museum of Northern Arizona, encapsulates the insidiousness of the white colonialist enterprise. A young Diné boy, wearing dungarees with a concho belt and moccasins embellished with turquoise-studded silver stars, letters into the russet-tan dirt, with a stick, “Santa Fe All the Way.” In the distance, that self-same train, supposedly filled with tourists, rumbles across the boy’s land. Those tourists are eager to experience “the strange corners of our country,” as another ad described areas including the Hopi mesas, Colorado Plateau, Navajo country, and on to the Grand Canyon.

In this image, a hard reality lies beneath the manufactured romance. In the early 20th century, the marketing departments of the Santa Fe Railroad and the Fred Harvey Company (which established restaurants and hotels at stops along the railroad) comped well-known artists in exchange for paintings they could use in brochures, posters, calendars, and pamphlets to sell a particular version of the Southwest. A version in which Native peoples complacently welcomed trains crisscrossing their land, complied with one-dimensional versions of their lives and livelihoods, and welcomed the opportunity to transform their arts into tchotchkes for tourists.

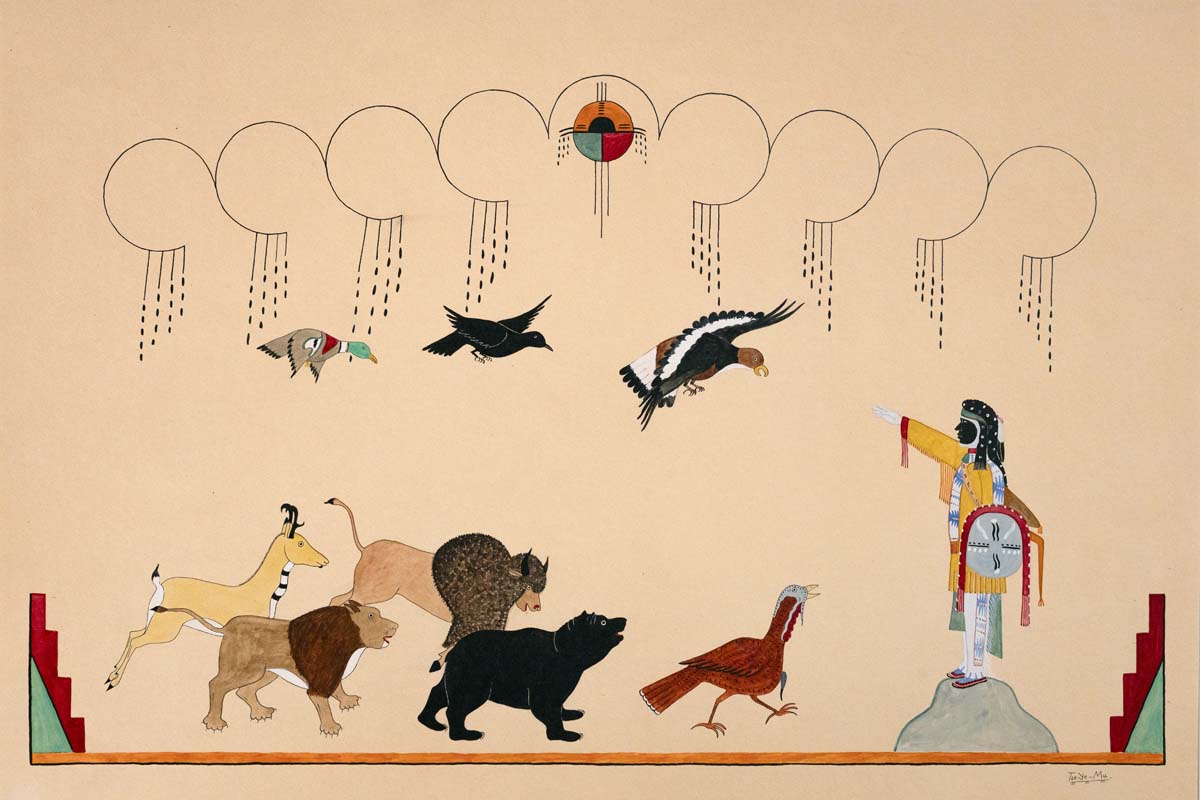

The Southwest’s landscapes were seen as sensational, stunning, sublime. The Southwest’s Indigenous people, seemingly untouched by “modern” life, were portrayed as exotic, mysterious, innocent, and yes, subaltern: also, completely down with colonialism. Of course, nothing could be further from the truth. Just as their land was being taken and sold, so were Native cultures and their people. Still, they adapted. As this exhibition, drawn from the museum’s Fine Art and Ethnography collections by curator Alan Petersen, points out, some Native people took the opportunities offered. Tewa/Hopi potter Nampeyo—whose influence on the art of European modernists has raised questions of Indigeneity and modernity—was a popular demonstrator of Native arts, according to the exhibition didactics. Native-made baskets, jewelry, pottery, and blankets brought income into families. Encouraged by marketing staff to craft objects tourists could easily carry home, Native artisans also made long-handed silver spoons and carved silver salt cellars.

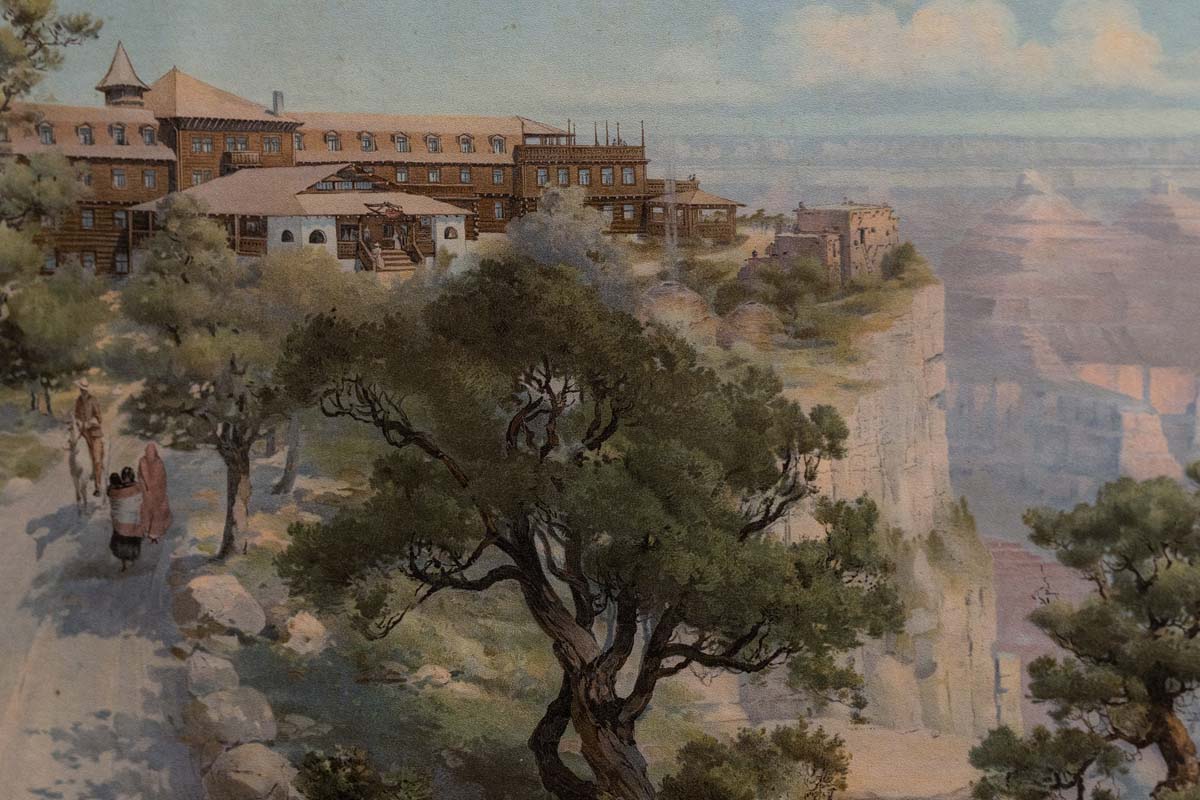

Louis Akin’s painting El Tovar (1907) also exemplifies the illusions such fine art/marketing materials created. The Harvey hotel, designed by architect Mary Colter, sits solidly atop the south rim of the Grand Canyon in an atmosphere of dreamy pastels and adjacent to a Hopi pueblo, while a man on horseback and two Native women walk the road. “AI manipulation of reality is nothing new,” Kristan Hutchison, the museum’s director of public engagement, astutely observed as we viewed the exhibition. Nor has the popularity of the Southwest lessened in the early 21st century, as city tourism campaigns and social media continue to drive millions of visitors into fragile and increasingly degraded landscapes. Selling the Southwest successfully delves into and unpacks an aspect of colonialist mythology that endures to this day.