Sapira Cheuk: New Vessels, Unmade Structures

June 28 – August 1, 2019

Core Contemporary, Las Vegas, Nevada

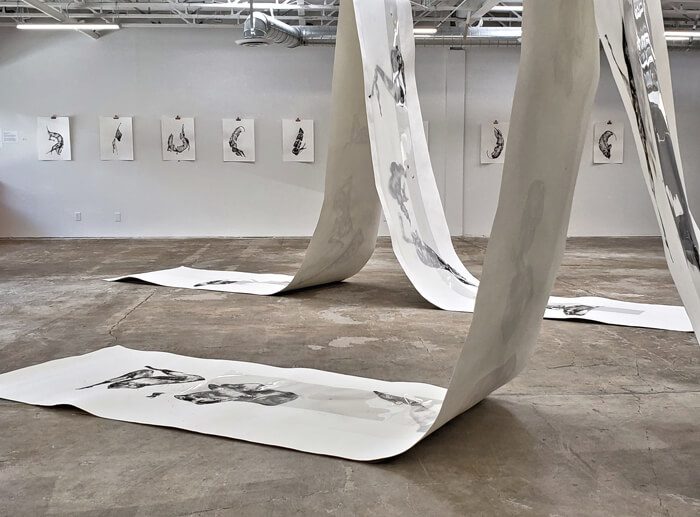

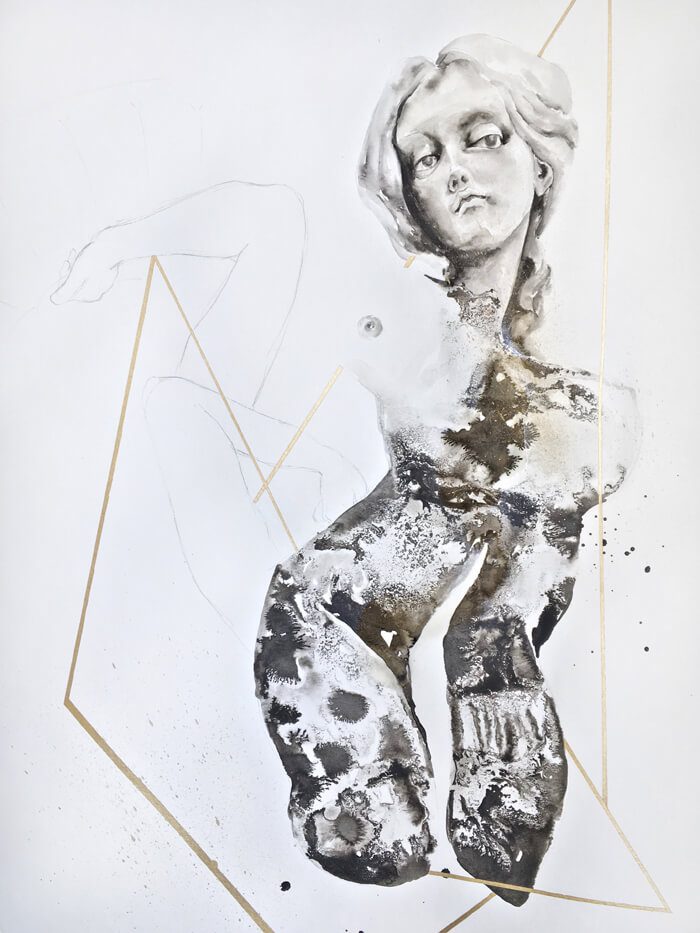

I show up while a workshop is in progress at the back of Core Contemporary. The artist Sapira Cheuk is teaching some beginner techniques of Chinese brush painting to local Las Vegans. The participants are intent on painting their own inky bamboo gardens. I survey Cheuk’s exhibition beyond the workshop. Globular figures seem to wiggle, tumble, float, or crawl across pieces of thick, white paper. Two particularly large sheets of paper cascade down from the ceiling at the center of the gallery. Sometimes they’re partially covered by a layer of clear film. About thirty smaller iterations occupy the walls. Here and there: a curled hand wearing what could be an elbow-length glove; firm, flexed ballet feet; sturdy legs in the air; and extra-long legs with powerful thighs. There are no bamboo shoots anywhere, but from dappled gray spots emerge crouching or twirling figures, some leaf-like, others more lobster. Clumps of gold leaf, gold spray, and splatter suggest mist, motion, or strange scabs. Elsewhere, in ghostly light pencil: gesturing hands, a wayward cornice.

If this collection of bodies could speak, I imagine they might say, I’m many bodies, hands and feet flying, dancing. I’m not necessarily sexual, or even gendered per se. All bodies being battlegrounds, my answer to the threat of being objectified is to refuse predictable structure. Let my nipple slide down some. Let my belly, butt, or eye be a series of thin, transparent washes. A void forms at my center. I am powerfully permeable. Volcanic gases and liquids build up in me. Particles split and pass through me. They are me.

In Venus, You’re Still My Muse (2019), for example, ink, watercolor, graphite, and acrylic interact and flower on paper to depict Venus in her form at Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas, a copy of the Venus de Milo. The Ancient Greek Venus is more laid-back, though. The Vegas version angles forward. Cheuk’s seems to be screwing up her face, quizzically considering her future, while also leaning into it, even if her body floats loosely in space and also appears churned and cloudy inside.

Cheuk arrived in Las Vegas via San Bernardino and Riverside, California. We’re both new to Sin City. As her workshop continues, Cheuk demonstrates that bamboo leaves are best rendered with one straightforward brushstroke and are most realistic in groups of three or five. I confess that Las Vegas has been an adjustment for me, coming from Baltimore. The heat, the cacti, the open sexuality, the presumptions about women’s bodies. Pleasant and confident, Cheuk observes that the dominant body type in Las Vegas seems to be different. She muses that where she was before, in Southern California, she lived among lean, suburban gym bodies. Here in Las Vegas, she’s noticing what might be defined as strong service-industry bodies, perhaps formed by long hours of carrying and carting.

In a statement on the wall in the gallery, Cheuk writes about beauty and escaping the othering of bodies. “I portray a moment in time where the body has been distorted,” she writes, “causing the removal of the other’s purpose. This demolishes the physical and metaphysical structures that the figure has been forced to uphold, thus allowing its agency, its selfhood, to be returned.”

I think about President Trump grasping at women, and I wish that, next time, he would come up empty. I think, too, about his holding bodies captive in cages. Were he unable to hold, were his fences no good, his horrible grasping, now, wouldn’t make contact. It wouldn’t keep us. What if he were unable to seize or ensnare? If only he were just grasping at straws. Cheuk’s painted bodies refuse domineering snatch-and-grab. They’re Venuses, wispy forms besting mortals.