Photojournalist Russel Albert Daniels posits his family history as a bridge to larger investigations into Indigenous histories and the legacy of colonial violence and displacement in the American Southwest.

SALT LAKE CITY—Russel Albert Daniels recalls hearing stories about his ancestor Rose from an early age. Their shared name was forged by Rose’s marriage to Aaron Eugene Daniels, the white man who trafficked her from a series of abductors, in a harrowing journey from what is now Arizona to present-day Utah. Her life, just like the stories that survived well beyond her impressive 104 years, marks a horrific if crucial part of American history often relegated to the shadows—that of the enslavement of Indigenous persons in the land we now refer to as the United States of America.

To Daniels, learning of Rose’s enslavement personalized his understanding of Indigenous genocide and cultural erasure in the American Southwest and beyond. For years, his work has attempted to reckon with this history by documenting, through the photographic lens, the bridge between the familial and the historical.

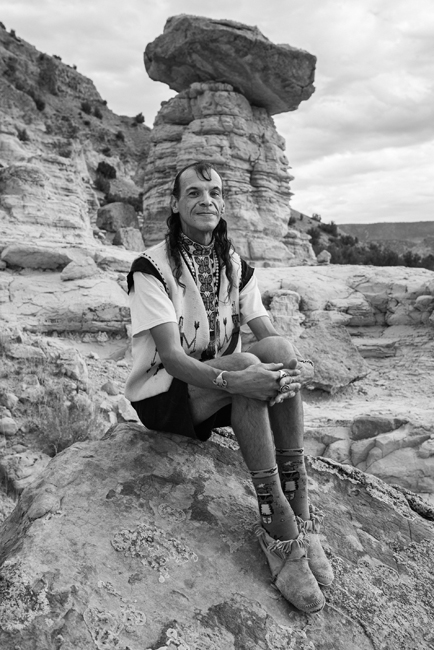

I met the soft-spoken, contemplative Daniels at a gathering this past summer organized by mutual friends. We continued our conversation over breakfast and later at his home studio in Salt Lake City’s Millcreek neighborhood, a resting spot for an artist continually on the move.

The Utah Museum of Fine Arts recently premiered Shaping Landscape: 150 Years of Photography in Utah, an exhibition featuring one of Daniels’s photographs. UMFA also acquired two of the artist’s works as part of its permanent collection. This comes after a recent string of achievements for the artist, including an exhibition at the Smithsonian Museum of the American Indian in Washington D.C., and group shows at the Minneapolis Museum of Art and the new museum at the Utah Valley University Museum of Art in 2023. Next year, his work will be shown in the Tacoma Art Museum exhibition The Abiquenos and The Artist. The show, curated by Patricia Marroquin Norby (Purépecha), the first Indigenous curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, is scheduled to run from May 18, 2024, through May 31, 2026.

When he’s not enmeshed in long-term projects, Daniels works as a freelance photojournalist. His work has taken him to diverse locales and his photographs have been featured in publications like National Geographic, Mother Jones, and ProPublica. His work highlights important topics such as preservation efforts for endangered species populations, the crisis afflicting public lands, and the desecration of Indigenous remains.

Daniels’s work touches on an indelible truth—the incalculable impact of the many Indigenous cultures who have called this region home for over 10,000 years. Yet not by accident, the Mormon pioneers who fled religious persecution to arrive in the Salt Lake Valley in 1847 continue to dominate popular associations with the desert state. Distinct from the direct forms of colonization and genocide is a specific type of cultural erasure that posits white settlers as the population that cultivated a land once deemed inhospitable to other Euro-American explorers.

Where the state’s namesake is often lauded as an homage to this Indigenous heritage, it’s often done superficially. After all, Utah is derived from the sprawling and powerful Ute tribe, for which historical and geographic iterations remain. Modern-day Utahns lack a critical awareness of not just the history that preceded their ancestors’ arrival in the Salt Lake Valley, but the acts such ancestors initiated following their arrival.

The story of Rose Daniels originated on Daniels’s father’s side of the family, his great-great-grandmother. While parts of her narrative were passed down through generational lines, “There were a lot of holes in this story,” Daniels tells me. “I had to do some archival work to uncover more of the story.”

Rose was born sometime in the mid-1800s in Dinétah, the Navajo homeland, the region corresponding to what is now Northern Arizona. As a small child, Rose, a member of the Diné (Navajo) tribe, was taken captive by the White River Utes and trafficked to different Ute bands. Eventually, she was traded to early Mormon frontiersman and polygamist, Aaron Daniels. Rose spent decades as a servant to the Daniels family. She later married and had four children with Aaron. Rose settled back in northeastern Utah in the late 19th century, where she was affiliated with the Uintah and Ouray Reservation. Daniels and his siblings are the first generation to be born outside the Ute reservation.

In order to tell Rose’s story, Daniels embarked on a photographic project about the role of the past in shaping the perspective of the present. This inspired Cautiva, an ongoing photographic project that spans centuries—beginning with Spanish colonization and enslavement in the 16th century, to French and British colonization, followed by Mormon conquest in the 18th through the 20th centuries, and culminating with the crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls in the present day. The first iteration of Cautiva, entitled The Genízaro Pueblo of Abiquiú, was the subject of Daniels’s exhibition at the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian.

“What a lot of people don’t know is that there was a slave trade happening here in Utah. Wherever the Spanish went, slavery followed,” Daniels explains. “We still don’t account for all of the colonial violence inflicted on Indigenous people.”

While his work requires him to travel throughout the country, Daniels has cultivated a particular interest in documenting the Southwest, Great Basin, and the Mountain West. His work aims to explore the persons who have been long neglected by historical narratives and to uncover what he calls the “aftermath of Manifest Destiny.” A renewed focus on Civil Rights in the wake of the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests has helped elevate his profile as an artist and created new opportunities.

Daniels seems, on some level, to contend with a stereotype as old as photography itself—that the medium is less of an artistic craft than the more traditional painting and sculpture. Though attitudes have markedly changed, photography’s didactic properties and seemingly less laborious application, for some, lead to some hesitation in referring to its practitioners as mere artists. Yet, Daniels reminds me in a breakfast conversation (over some of the best pancakes in the city) that he considers himself an artist first, then a photojournalist.

“I see documentary photography as tools in my bag as an artist. I am an artist who uses documentary photography. I moonlight as a photojournalist… [but] my ultimate goal was to bring it all together and always have an artistic aesthetic to my documentary photography.”

His enthusiasm for the aesthetic properties unique to photography is apparent, as he relayed his love of developing prints as well as black and white film. In high school, he took his first photography course and even built his own darkroom.

In 2009, Daniels earned his Bachelor of Arts degree from the School of Journalism at the University of Montana. He’s traveled and lived in many places, including stints in New York City and San Francisco before moving back to Utah, a place he had always loved and missed. The reaction to Daniels’s work reveals a yearning to uncover the ample history this region possesses.

In a time when elected officials openly tout historical erasure as a rallying policy goal, the history Daniels uncovers reminds us why those very figures are keen to suppress such historical episodes and distract us from the deeply painful legacy they present. The beauty of Daniels’s work rises to the surface, beckoning a deeper investigation into humanity that lurks within the frame—one we can all choose to see if we are open enough.