In the tiny town of Fort Garland, Colorado, Unsilenced: Indigenous Enslavement in Southern Colorado by Chip Thomas (the artist known as jetsonorama) spotlights uncomfortable and paramount histories of Indigenous captivity.

Unsilenced: Indigenous Enslavement in Southern Colorado

June 18, 2021-ongoing

Fort Garland Museum and Cultural Center, Fort Garland, Colorado

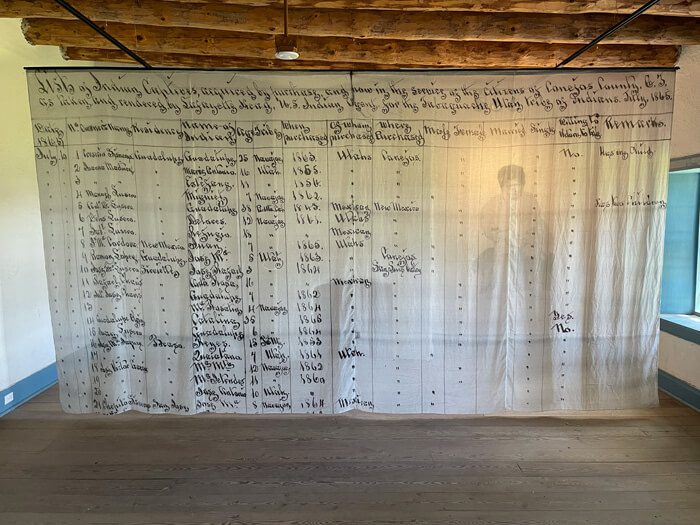

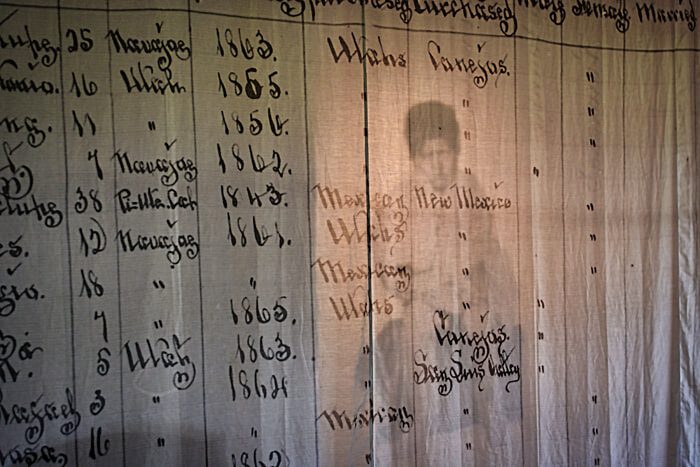

Walking into an adobe building constructed in 1858 as a military outpost, visitors are greeted, in two separate rooms, by multi-paneled and stitched sheets that hang and shiver in the breeze from nearby open windows. Ornate handwriting, separated into seventeen columns, lists statistics—date, age, residence, “name of Indian,” “when purchased,” “willing to return to tribe.”

These aren’t just names and data on display at the Fort Garland Museum and Cultural Center, located in southern Colorado approximately thirty minutes east of Alamosa. These are Indigenous captives. Illegally-held prisoners. Real people. Someone’s ancestor. Unlike chattel slavery in the South, Native American enslavement was forbidden yet practiced in the region.

The artist and physician Chip Thomas, also known as jetsonorama, amplifies this and other little-known facts in Unsilenced: Indigenous Enslavement in Southern Colorado. The heavy yet salient exhibition is part of History Colorado’s Borderlands of Southern Colorado initiative, which is prioritizing the voices, legacies, and stories of Indigenous, Chicano, and Mestizo people in the San Luis Valley.

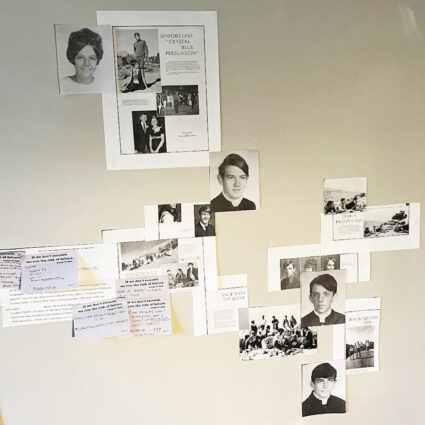

Thomas’s two oversized reproductions of an 1865 census count—one from Costilla County, the other from Conejos County—anchor the streamlined and potent installations. The exhibition, located in a space that housed a Kit Carson exhibition for sixty-eight years, also displays archival images of Native captives, including a circa-1871 portrait of Juan Carson, Kit Carson’s Indigenous son who was assimilated into the elder Carson’s ways.

According to the two census documents, a total of about 160 Indigenous people were held captive, displaced, culturally violated, and assimilated into domestic servitude in the San Luis Valley. But the story is more complicated, and also, unfortunately, predictably tragic.

Lafayette Head is the person responsible for the original handwritten manifests. A Colorado lieutenant governor and so-called Indian agent, Head was tasked by president Andrew Johnson to investigate the illegal practice of Native enslavement in the West.

After Head tallied the counts, he wrote a letter to then Colorado Territory governor John Evans, which is reproduced and viewable in an accompanying exhibition notebook.

“I have notified all the people here, that in the future, no more Captives are to be purchased or sold as I shall immediately arrest both parties caught in the transaction,” Head writes with apparent defiance. “This step, I think, will at once put an end to this most barbaric and inhuman practice, which has been in existence with the Mexicans for generations.”

However, there’s something missing from the letter and from the census documents: Head himself held Native captives inside of his compound, and this information appears to have been excluded from any and all official documentation. (A companion installation in Conejos County features a Chip Thomas wheatpaste version of a census document on a building believed to have housed Native slaves. Due to safety concerns, Southwest Contemporary is unable to disclose locational details. For more information, contact the Fort Garland Museum and Cultural Center at 719-379-3512).

Additionally, according to Virginia Sanchez, author of Pleas and Petitions: Hispano Culture and Legislative Conflict in Territorial Colorado, Head was the richest person in Conejos County in 1870 and likely amassed his fortune through the sale of Indigenous slaves, including Navajo children.

In this and other related contexts, the exhibition feels especially topical considering conversations around the Land Back movement, the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) awareness campaign, and present-day struggles combatting human and sex trafficking. It’s a horse’s pill to swallow, but that’s precisely one of the inescapable and magnified truths of the exhibition.

The visual impact of a sparse and stark white sheet with antiquated black writing scuffles with the ideas of place, identity, and “belonging,” especially considering the site-specificity of the installation—the viewer is learning about Native enslavement in direct proximity to the barbarous acts. The physical scale of the installation feels like a reoccupation of the space and, as an extension, a recentering of the Indigenous narrative in the San Luis Valley.

As the oversized census documents, with terse rows and columns, sway in the breeze, the large photographs of Native captives, one which is displayed behind the sheet, seem to rouse. The piercing eyes and the sad stares laser into the soul. There’s nothing comfortable about the experience, and it shouldn’t be.

Because Head’s original penmanship is challenging to decipher, the exhibition could benefit from additional information and literature at the show’s start. Otherwise, a viewer might not dedicate the time and effort required to take these histories home with them.

Unsilenced: Indigenous Enslavement in Southern Colorado is on display at Fort Garland Museum and Cultural Center, 29477 Colorado Highway 159. There was no closing date at the time of writing. An event entitled “The Tomorrow of Violence: Slavery, Kinship, and Community in the Borderlands” is scheduled to take place at the Fort Garland Museum from 2 to 8 pm Thursday, September 30; it’s free but an RSVP is recommended.