In Plein Air at MOCA Tucson, artists challenge norms in paintings, installations, and video works that confront the white gaze that privileges colonizer culture and systems of oppression.

Plein Air

May 14, 2022–February 5, 2023

Museum of Contemporary Art Tucson

Seven contemporary artists counter historical assumptions and aesthetics in the exhibition Plein Air exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tucson, where their work shatters the colonial gaze and forges new relationships with land. They’re part of a new generation of creatives expanding not only who works in plein air, but also the materiality and meaning of this evolving art practice.

Art historical accounts of Western painting practices typically place the origins of plein air painting, which is titled after a French term for painting outdoors, in the 19th century. Early practitioners included English painter John Constable, followed by French Impressionists such as Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Many credit the technique’s rise to the invention of tubes of paint, which made it easier to transport and use materials outside the studio.

A small oil painting by Texas-born, New York-based artist KB Jones (Mountain, 2020), which is one of the first works viewers encounter in this exhibition, calls back to those early works. Nearby, watercolor on paper studies convey observations of oil drilling that informed her Intervention (study) created in 2020 using ink, house paint, and crayon on canvas. It’s one of many pieces that amplify the fascinating breadth of materials used in contemporary plein air constructions.

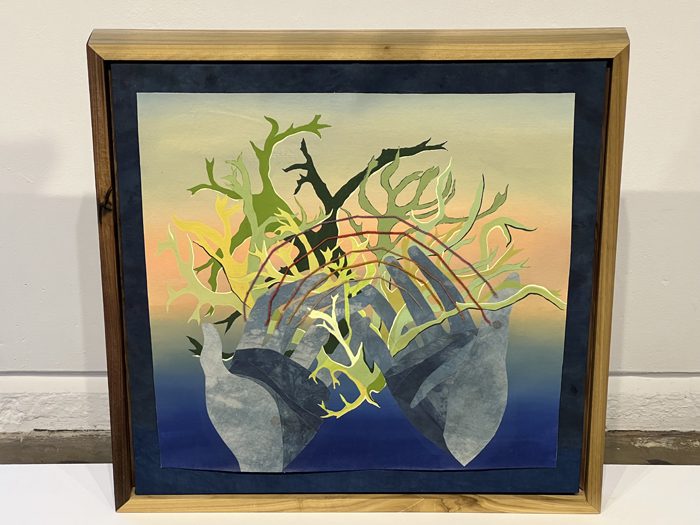

Here, the materiality of two works by California-based artist iris yirei hu are particularly compelling. Hu’s installation I swallowed the sun and cracked the sky. I ate the delight. (2022) features a small sculpted piece of artist-hewn fish leather suspended over a platform where viewers also encounter myriad objects including a rock, a ceramic vessel, a bottle of lichen ink, dyed fabrics, and two upright framed works.

Hu’s approach signals a significant departure from historical plein air painting, in which artists used traditional materials to render replicas of what they saw. Rather than passively painting pastoral scenes, she’s manifesting landscapes born of her own inner world and kinship connections, using a wealth of natural and biological components such as earth, plants, seashells, petrified wood, and her own hair.

But there’s another shift suggested by her work and works by other artists featured here. Collectively, they position land as a co-creator rather than an object to be owned and exploited through extraction, while also challenging the white gaze that privileges colonizer culture and systems of oppression.

Paula Wilson, a Black female artist born in Chicago and based in New Mexico, shows two pieces that powerfully counter reductive, homogenous perspectives with complex layers of form, color, texture, and pattern. Plein Air includes Wilson’s Salty + Fresh, a 2014 video conceived as the origin story of a painting, which was filmed on the “colored only” Virginia Key Beach in Florida.

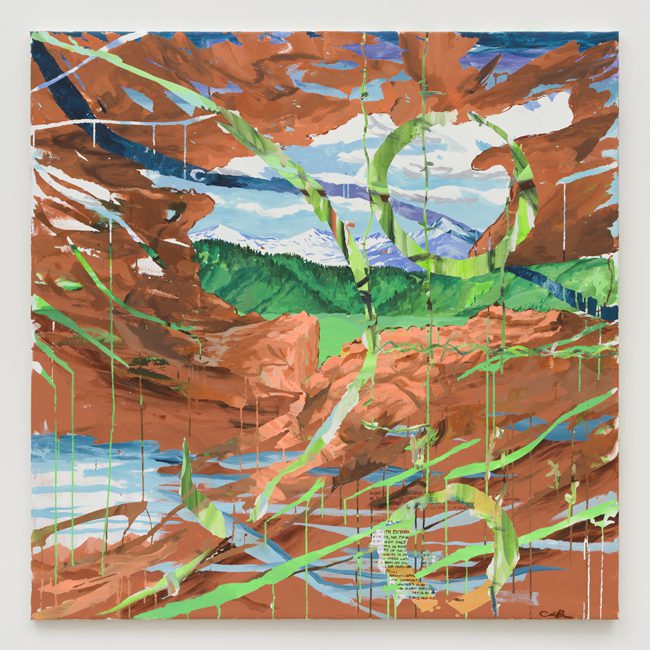

The exhibition also includes How Mora, New Mexico Stopped Fracking, a 2022 acrylic-on-canvas painting by Esteban Cabeza de Baca, a California-born artist based in Queens, New York who counters linear, monolithic perspectives in part by mingling landscape, graffiti, and pre-Columbian imagery. Along one side of the canvas, he’s written text in all capital letters that read “green New Deal is possible” and “ban fossil fuels,” which hint at the environmental activism at play in both his own work and this art show as a whole.

Plein Air was organized by California-based curator and researcher Aurora Tang, who serves as program manager for the Center for Land Use Interpretation in Los Angeles. The exhibition highlights several artists whose constructions are rooted in research rather than the romanticism that drove so many early plein air proponents.

Those artists include Hillary Mushkin, an artist and researcher based in California who’s showing works from her 2020-22 series Incendiary Traces: Survey to Surveillance that includes a trio of photographic prints showing the boundary between Mexico and the United States at different points in time, as well as an accordion-style artist book displayed on a shelf and several drawings exhibited inside a glass-covered table.

Similarly, the New York-born and California-based artist Sterling Wells homes in on a particular site with their Infructescence (2020/2022) installation comprising a video filmed in a forest recreation area, which is positioned near a mixed-media construction consisting of a watercolor-on-board painting and objects found at the site.

Much like the invention of paint tubes allowed earlier artists to render landscapes through direct experience, video technology is helping contemporary artists create new iterations of plein air methodologies. Three videos by Tucson-based artist Susanna Battin are included here, along with objects reflecting the ways people’s relationships with land are impacted by visual culture.

Clearly, these artists are pushing far beyond the historical conventions of plein air painting, applying their own agency to the task of transforming a significant art historical tradition while delivering a profound cultural critique of contemporary landscapes both interior and exterior.