Patrick Dean Hubbell’s exhibition Tack Room at Gerald Peters Contemporary in Santa Fe serves up a powerful discourse that challenges the representation of Indigenous peoples.

Patrick Dean Hubbell: Tack Room

August 12–October 22, 2022

Gerald Peters Contemporary, Santa Fe

Patrick Dean Hubbell’s (Diné) installation Tack Room at Gerald Peters Contemporary is a sharp critique of representation and agency in the canon of Western art, specifically when it comes to Indigenous peoples from North America. The show originally premiered at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2020 where Hubbell was completing an MFA, and now appears in an expanded iteration at Gerald Peters with new paintings and installation works.

The gallery, set up as an imaginary stable tack room, features saddle racks and stands that act as plinths to hold and house the works on view. Made from materials sourced from the artist’s ranch, the elements on which Hubbell mounts his work create a level of autobiography, while concurrently interrogating perceptional readings of the American West in dominant culture and challenging the colonial binary of the “cowboy and the Indian.”

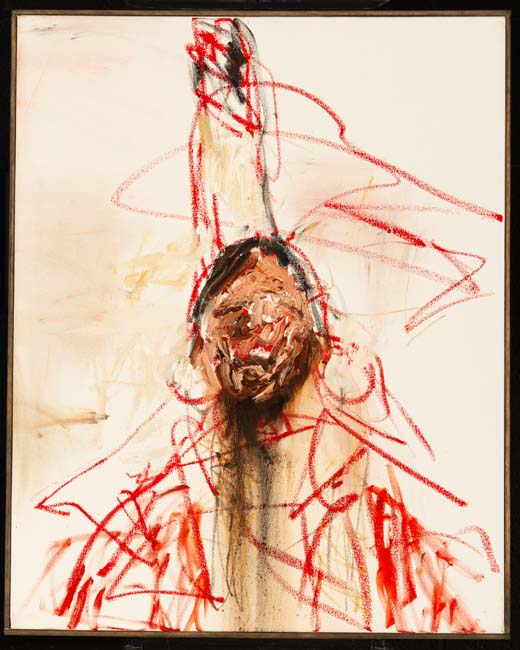

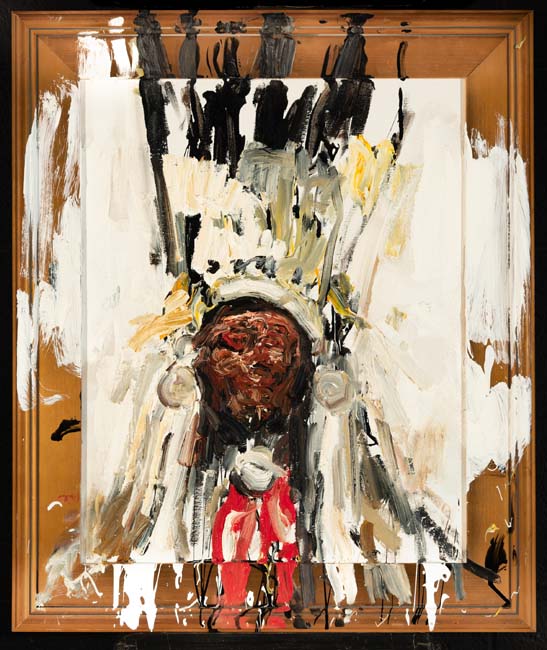

The works in the show have a strong interconnectedness, taking the viewer on a narrative journey that eschews the damaging tropes Western art has installed of the “romantic Native American” while probing into those deep-seated stereotypes that surround Indigenous North America. Paintings in the exhibition reference source material by settler artists, including portraiture by 19th-century artists Fredric Remington and George Catlin, who spent much of their careers depicting Indigenous peoples. These reimaginings of Catlin and Remington, among others, manifest in unframed canvases of drawings of both Indigenous peoples and cowboys, realized through the artist’s use of blind portraiture. These gesturally abstracted works lay overlapping across the wall-mounted and freestanding saddle racks—evoking a sense of utility, as though they are going to be picked up and used to accomplish a specific task. That these works are painted and drawn with the artist looking away from the canvas, in the form of the surrealist method of automatic drawing, illustrates the deep level in which harmful and fixed stereotypes, perpetuated by the dominant culture on Indigenous peoples, are tattooed on the psyche of both Native and non-Native audiences alike.

In Dismantled (2022), a pile of frames with canvases extracted from them lies on the floor as a form of detritus of European modes and classifications of artistic production. With this, Hubbell abjures the structures and strictures placed on artists working in an ever-evolving creative field that still seemingly finds itself bound to antiquated modalities and understandings of what is “high art” and what is not. Hubbell creates work that is liminally situated at an intersection of painting, weaving, sculpture, and installation that transcends an easily reached or decided upon definition.

When the frames are not cast to the floor in an assemblage of resistance, some become part of the painting itself, with the pigment smudged, dragged, and left bleeding onto gilded edges like in They Want the Portrait, Not the People (2022). The portrait—which articulates the visage of an Indigenous person wearing a feathered headdress, though highly abstracted—denotes a sort of anguish or feeling of distress in the sitter. It brings to mind the psychological portraiture that Fritz Scholder (Luiseño) created later in his career—expressing a generational trauma experienced through colonization, forced assimilation, and genocide. In this, Hubbell creates an environment where violence and melancholy are captured and fused with a resurgence of agency.

In Your Healing Touch, Equine Medicine Blankets (2022), the frames act as armatures for paintings, paintings which reference Diné weavings, carefully folded and draped across the stretcher bars like blankets. Here, the artist achieves a flattening, or perhaps more accurately a near obliteration, of a colonial hierarchical canon of artistic accomplishment and categorization which historically placed painting at the top of a steep pyramid of artistic value, relegating other forms of artistic production, such as weaving and textile-based art, to an arena of craft. By treating these works as simultaneously painting and tapestry, Hubbell dislodges colonial tropes that pit high art against craft and traditional versus contemporary.

Tack Room serves up a powerful discourse that challenges the captured and fixed meanings and representations of Indigenous peoples, prying up the foundations of a Euro-centric art historical canonical structure in an exacting and unflinching manner. Hubbell pushes the viewer to consider their role in the shaping of the imagery of the American West, perhaps strategically asking more questions than he answers. By implicating the viewer in such a way, the agency is shared, and thus the responsibility to upend harmful readings and stereotypes of Native peoples is shared as well; forcing a much-needed environment that actively makes and holds space for new understandings.

Patrick Dean Hubbell: Tack Room is on view now through October 22, 2022 at Gerald Peters Contemporary, 1011 Paseo de Peralta, Santa Fe, NM 87501