In So That We May Fear Not in Salt Lake City, artist Jesse Meredith documents an American militia group and illustrates contradictory narratives of maleness and patriotism.

Jesse Meredith: So That We May Fear Not

March 11–April 22, 2022

Finch Lane Gallery, Salt Lake City

Surrounded by camouflage print—hanging from a wall, in a textile piece on the floor, and in photographs—I find myself creeping up on a man in tactical gear in the C-print photograph All or Nothing. Like a wildlife photographer who veered off course to capture the hunters instead, Jesse Meredith looks closely at a group of white American militia members. Etched photographs and multimedia pieces in So That We May Fear Not, up through April 22, 2022 at Finch Lane Gallery in Salt Lake City, give viewers a window into an Illinois-based group Meredith embedded with in 2016.

“I’ve always been obsessed with camo,” says Meredith in a phone interview with Southwest Contemporary. “The militia group [featured in the show] doesn’t have a set uniform, so everyone gets to choose their own. There are all sorts of assumptions you can make about an individual based on the one they choose.” For viewers, the show will provoke a range of their own associations, especially after the January 6th insurrection, and provide a backdrop for thinking about American identities.

During his MFA program at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Meredith connected with the group through Facebook—he ended up on Donald Trump’s mailing list without ever signing up—and introduced himself as a photographer interested in the movement. The members of the all-male group accepted Meredith, who’s a white man.

“There’s a lot of you are this, therefore you are that logic,” says Meredith, who felt a genuine sense of bonding, especially as he’d been raised partly in rural upstate New York. “I still call some of the members friends,” adds the Salt Lake City-based artist who’s a current artist in residence at the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art.

As a Utahn with roots in rural parts of the state, when I look at All or Nothing, JP, or Echo, I have to admit the scenes are almost mundane, like snapshots a coworker might show me of the first day of hunting season. (It’s no coincidence schoolchildren’s fall break is at the same time.) To most of the population in Utah, there’s nothing threatening about the lines etched on All or Nothing: “what do you lose/when you win.” But to the usual crowd that visits art galleries here, these words mean something different—political and destabilizing.

And here’s the rub: how do we consider the militia’s practices that, in some of Meredith’s pieces, ring of the joys of boyhood and in others, the threat of domestic terrorism or the denial of objective reality? Plausible, a photograph of trucks parked in a field, features the words: “It wasn’t me/It was/Everyone else” etched into the glass. The Illinois group Meredith photographed didn’t have guns because the state doesn’t permit open carry, but in Utah and other open-carry militias, guns are central activity points. Without firearms in these photographs, these men feel much less threatening than the groups in our backyard.

The concept of people chosen for a special destiny, removed from a vague body of others, is also on view in The Few. The viewer has to invest to see the short projection of red words scrolling over perforated vinyl—the camo pattern is disorienting to the eye. “The Few started with the poem,” Meredith says. “The content was much more standard patriotic fare, but I trimmed it to try to lay bare the actual structure… it resonates with a general Libertarian mindset.”

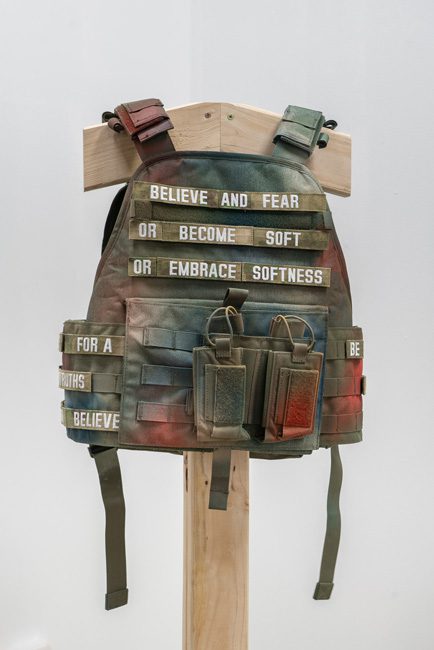

Meanwhile, Soft Body reads in part: “The winds of change break the old tree but the grasses bend and grow in the new air. Prepare yourself for a multiplicity of truths you wouldn’t believe. Believe and fear or become soft or embrace softness.” To me, what Meredith aims for—selecting language that blurs the lines between sub-political or cultural orientations—he accomplishes. His poetry pulls me in, a resonance with my childhood or college reading of American transcendentalism, even if in any other situation I’d give a tactical vest a wide berth.

Meredith hopes that people take away a new perspective during the current moment when American culture is in historic flux and the logic of groupthink has been rocked by last year’s insurrection. Militia mentality seems rooted in an American nostalgia that, depending on your take on the Second Amendment or how squeamish seeing grenades indoors makes you, could feel completely alien. “It’s definitely a romanticization of the self—casting the self as the hero of this narrative, but the worry is that there still could exist the temptation to use these skills for violence,” Meredith says.

Jesse Meredith: So That We May Fear Not shows at Finch Lane Gallery, located in Reservoir Park in Salt Lake City, through April 22, 2022.