Jae Ko’s artworks at Robischon Gallery in Denver address the Southwest’s drought conditions and the rise of water speculation in the futures market.

Jae Ko: New Works

April 7–June 11, 2022

Robischon Gallery, Denver

Massive installations of rolled paper stacked atop one another from floor to ceiling are the hallmark of Jae Ko’s art practice. Each roll alternately flattens and bulges, creating white waves that are awe-inspiring in scale and disconcerting in their faux-tenuous construction. Like a snapshot of a wave at or near its peak, they capture moments of potential kinetic energy that could drown viewers in their fibrous crush. These expansive artworks, which fill entire gallery spaces and museums, are striking in their appearance and execution; rightly, they have brought acclaim to this Korea-born and Maryland-based artist.

Located in the LoDo neighborhood of downtown Denver, Robischon Gallery previously exhibited Flow—one of these large installation-based works—in Ko’s 2017 show Concatenation II. But in her 2022 show—New Works—the artist focuses on smaller, wall-bound objects that contain both painterly and sculptural qualities.

Eight of the ten pieces featured in New Works are approximately one foot in height and length, with two pieces measuring just over three feet tall and wide. While these artworks are not of a grand scale, they are of no lesser quality, nor are they less worthy of our critical attention.

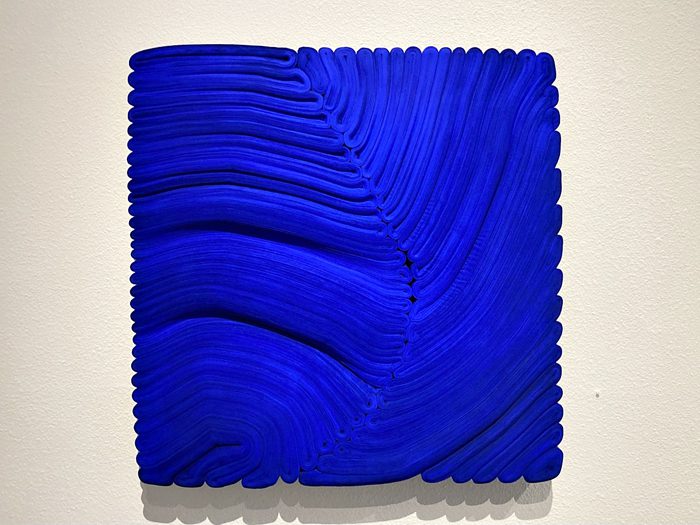

As with Ko’s installation-based work, she constructs her wall-hanging objects from rolled paper. But unlike her more monumental pieces that retain her paper’s natural color, she dyes the rolls in ultramarine ink and sets them with glue.

The shapes of the eight smallest objects resemble glyphs, suggesting some ancient language long lost to contemporary civilization. Staring at these artworks, they convey an effort at—or aura of—communication: we believe they are a language; but without the ability to decipher the content of the communiqués, we remain alienated from shared discourse. In this way, the pieces grapple with the tension between the recognizable and the inexplicable.

Conversely, the two larger works—JK2109 A and JK2109 B—employ a more traditional rectilinear form with the outlines of each individual paper roll creating ribbed contours along their perimeters. Rather than the glyph-like quality of the smaller pieces, the interior folds and bends of JK2109 A and B are reminiscent of tidal currents and the overhead maps cartographers use to plot them. These forms, coupled with the fact that Ko uses ultramarine dye to color her paper, direct the viewer into decidedly aqueous interpretations.

If the color and shape of Ko’s objects gesture toward the oceanic, then her materials evoke monetary concerns. Robischon’s marketing copy for New Works notes the artist’s “distinctive technique of utilizing… adding machine and cash register tape” as her source material. While increasingly antiquated in use, both adding machine and cash register tape are emblematic of consumer and capitalist culture. They are, quite literally, a document of exchange: paper registering marks that indicate the transfer of cash or credit for goods or services sold (or, one could argue, the glyphs of modern consumerism).

JK2109 A and B’s confluence of water and finance, then, offers us an aesthetic opportunity to consider a cultural concern of our contemporary moment. Anyone living in the western regions of the United States knows of our current struggles with drought and water rights. As water reserves shrink and populations explode, the Southwest and California approach critical shortages in supply, directly impacting agriculture, livestock, and other industries. Some experts worry about the availability of clean drinking water for those living in this region.

In 2020, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange and NASDAQ began selling water futures along with other commodities already on the market, such as gold and oil. While advocates of this move argue that “water trading could better align water supply and demand in the face of growing scarcity,” detractors claim it’s a “cynical attempt at setting up what’s almost like a betting casino so some people can make money from others suffering.”

Regardless of one’s allegiance on this issue or how one couches their argument, the introduction of water into the futures market signals an escalation in the capitalization of a basic human need. Indeed, by trading water, this necessary element of survival has become hyper-commodified. Doing so re-orients our relationship to water: a publicly distributed resource becomes a speculative investment reserved for those with the necessary capital.

How then, we must ask, will water entering the futures market affect water distribution and consumption? As drought conditions persist in the Southwest and resources dwindle, will basic human needs become luxury items? And if so, who will have access to them?

Viewing Ko’s work through such a lens, obviously, provides its own set of complications. As abstract works of art, they provide no clear message or ideological platform. Indeed, interpretive models indicate more about the viewer than the artist or the artwork itself.

To that extent, should we consider Ko’s wall-hanging objects a criticism of the increased monetization of water? A call to action? Or, at the very least, do they instill a heightened awareness of our new reality that transforms basic survival into a speculative venture for investors? And, as a meta-critique, do these art objects as luxury items simply mirror the dynamics of financial speculation (i.e. art objects on the art market)? Perhaps, like any worthwhile artwork, they are all of these things.