Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, Scottsdale

October 14, 2017 – January 28, 2018

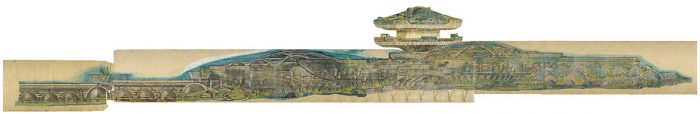

In an influential column in the New York Times in 1970, architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable called Paolo Soleri “the prophet in the desert,” positing that his ideas on the necessary comingling of architecture and ecology, or “arcology,” were not getting their due, especially in a time of mounting concerns about the environment. Soleri, who died in 2013 at age ninety-three, engenders mixed feelings about his legacy, partly because so few of his plans were actually built. Repositioning Paolo Soleri: The City Is Nature admirably keeps Soleri in the spotlight, along with exploring his work in geographical context. Arizona lays claim to Arcosanti, the domed city-in-progress in the hills about an hour north of Phoenix, where the architect tested his principles of dense communities living in ecological and cultural harmony. In the Scottsdale area, Soleri lived and worked at Cosanti, noted for its earth-cast concrete shells and terraced gardens and home to a well-known wind-bell foundry. Beginning in 2010, SMoCA curators mined ad hoc storage rooms at Arcosanti and Cosanti—as well as private collections—to unearth Soleri treasures: little-seen drawings and models, precious sketchbooks, the earliest examples of a silt-cast Soleri wind-bell, and, most spectacularly, several butcher-paper scrolls thirty feet and longer—his preferred drawing surface. One prime example is Macro-Cosanti Foundation Studies 2 and 3, envisioning a futuristic, high-density city (it merges three rolls of paper and unscrolls to a mighty 528 inches). The wide-ranging exhibition is not only the largest U.S. retrospective of the artist/architect since 1971, it makes the case for Soleri as “prophet” and, yes, even an eccentric, whose voluminous ideas are still worth examining today.

While SMoCA’s tightly focused Soleri shows in 2010 and 2013 helped polish his image, this third installment fulfills two satisfying mandates. First, with plenty of didactic material, it coherently moves viewers through phases of Soleri’s most fertile years, in the 1960s and ’70s, a time when he had left Italy for permanent residence in the States and when his contributions to our cultural history garnered the most attention. For instance, the exhibition displays a series of hand-screened posters for the popular counterculture “Silt Pile” workshops in Arizona. They catch the eye with bold colors and chunky typography. In another area, renderings of Soleri’s innovations in bridge-building share space with rarely seen models of those bridges in silt and plaster. The six-foot-wide model for Single Cantilever Bridge could almost be mistaken for the skeleton of a beaked creature. In addition, the exhibition addresses Soleri’s tense connection to Arizona’s other favorite architectural son, Frank Lloyd Wright. Drawings from Soleri’s student days at Taliesin West in the 1940s are accompanied by text conjecturing why the two might have had a falling-out.

A second mandate concerns aesthetics, that is, creating an immersive, attractive exhibition even without the historical lessons and semi-chronological flow. To that end, one enticing area is a niche hung with ceramic and bronze Soleri bells, varied in earth tones and their use of embellishments. In another room, the main draw is a five-foot-high model for Arcosanti that reveals a dense network of multistory columns, apses, bridges, and suspended walkways. Made of white acrylic, it gives off a porcelain-like glow. It’s a worthy glimpse into Soleri’s ability to think holistically about the efficient use of living spaces, water usage, sustainability, and other concerns. But probably the best evidence of aesthetic success is in the scrolls. To see them laid out in all their glory is to sense Soleri’s frenzied ambition and his refusal to be bound by architectural conventions. It becomes easier to picture him at his twelve-foot-long drafting table, unrolling butcher paper as he went along, sketching linear designs for urban living that remarkably cohere as the eye moves along them. Merely as drawings, they impress with their sometimes precise, sometimes gestural mixture of wax crayon, charcoal, oil pastels, pencil, and ink. If anything, the scrolls radiate “what could have been,” had Soleri lived to see more of his utopian plans brought to life. Our environmental precariousness continues on since the appearance of the Huxtable piece. How interesting that Soleri foresaw our need for arcology and saw it clearly.