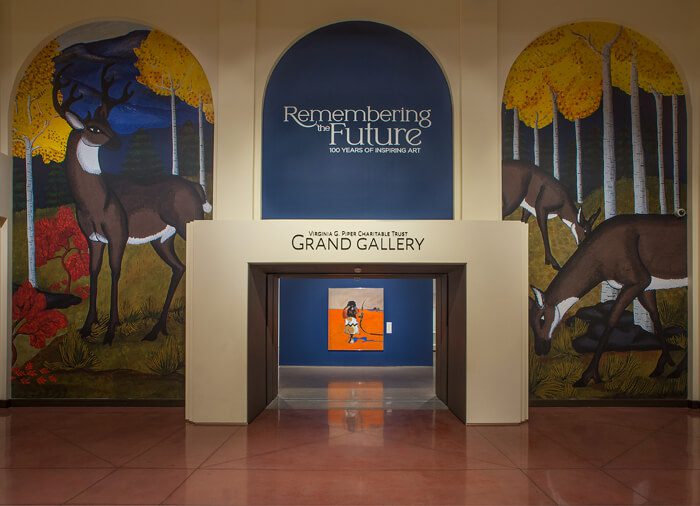

In Remembering the Future: 100 Years of Inspiring Art, the Heard Museum’s new exhibition tells the story of an artistic movement that is often left out of the broader story of American art.

Remembering the Future: 100 Years of Inspiring Art

October 26, 2021–January 2, 2023

Heard Museum, Phoenix

Eight buffalo dancers stand side-by-side, two-dimensional figures against a blank background. Their accoutrements are carefully detailed.

Nor far away, a plump coyote sits in a chair on a Navajo rug. A rainbow wraps around a wall; the window frames the Matterhorn. Coyote gazes at an Indonesian carving.

A century separates these paintings by Awa Tsireh and Steven Yazzie, yet despite their differences, they have much in common. Both use ancient symbols and rituals as fine art, and both are featured in the Heard Museum’s exhibition Remembering the Future, an exquisite presentation of the Native American fine-art movement that runs until January 2, 2023.

“We looked at how these painters held to the important values of their culture while looking to the future,” says Dr. Ann Marshall, co-curator of the seventy-five-work exhibition. “They explored other styles and grew. The American Indian fine-art movement runs parallel and intersects with major art movements.”

American Indians have used graphical representations to record events and honor spiritual beings for thousands of years. It wasn’t until the 1920s, though, that intentionally created fine art became part of the vocabulary.

“The Native American fine-art movement is left out of the general conversation about the history of American art,” says David M. Roche, Dickey Family Director and CEO at Heard. “This exhibition highlights how it has contributed.”

Awa Tsireh (the first nationally known Indian painter), Tonita Peña, Fred Kabotie, Carl Sweezy, and other 1920s artists painted ritual dancers. Their work is rich in detail, though flat with no background.

Later artists embellished on the theme, adding backgrounds or fantastical settings, then melding ancient icons with new styles: art deco elements in Waldo Mootzka’s Pollination of the Corn (1930s); figures wrapped in abstract flames in Oscar Howe’s Ghost Dance (1960); cubist Pueblo dancers in Pablita Velarde’s Corn Dancer (1970s).

The artists “show ceremonies that are important to their values, the ceremonies that they do for the well-being of the world,” Marshall says. “In the times we are in, we are looking to art as memory of what is important to carry us into the future.”

Social commentary arrived in the 1970s and 1980s, with art that addresses the Vietnam War, cultural appropriation, and environmental degradation.

There’s humor, too: Nora Naranjo Morse’s Pearlene (1987), a clay sculpture in the storyteller tradition, wears red lipstick and a tight skirt. Moccasins and stilettos reflect from horn-rimmed glasses in Jean LaMarr’s Just Wanna Dance (1984).

Coyote, the trickster of Indian folklore, makes three appearances: as a leather-jacket-clad urbanite who has “left the rez”; as a thief seeking to steal a caged parrot from the princess who gets whatever she wants; and in The Protector focused on the Indonesian carving in Yazzie’s 2021 painting. “This is the moment in question,” Yazzie says, “the intersection of spiritual beings, of the ancestral and the modern.”

“It’s specific and universal,” Roche says. “It’s about blending cultures and finding your place in the natural world.”

Which also describes the art in Remembering the Future.

sponsored by

![]()