In (RE)CONTEXT at the Rubin Center in El Paso, ten contemporary artists integrate text into their practices, recontextualizing and reappropriating words to create tools of social change.

(RE)CONTEXT: Artists Reconstructing Words

August 25–December 9, 2022

Rubin Center for the Visual Arts, El Paso

For a long time, we have been told that a picture is worth a thousand words, an idea that has shaped us into thinking that art is capable of transmitting knowledge without the need for textual communication. This understanding of the power of images might be well suited for the expression of abstract ideas whose messages are open to interpretation, but as the arts increasingly become powerful tools of social change, artists understand the urgency to incorporate concrete messages into their practice. This has led to a contemporary wave of socio-political artworks that rely on text to support their ideas, a phenomenon reflected in (RE)CONTEXT: Artists Reconstructing Words on view at the Rubin Center for the Visual Arts in El Paso, Texas.

The group show, organized by the center’s community curator Ramon Cardenas, brings together a group of ten artists and collectives whose work, through varied media, reflects on the struggles of contemporary society. Felandus Thames’s Respect (2018), for example, is carved out of hair brush bristles, offering a simple yet powerful message through an object that has multiple intersections in Black history; hair has historically been misused as a tool of oppression and assimilation, while the modern hairbrush was invented and patented in 1898 by Lyda D. Newman, a Black woman from New York.

José Villalobos’s pieces also reclaim objects, in this instance those reflective of the Northern Mexican machista culture, and he repurposes them to create messages of queer pride. In Esto es mi ser (This is My Being) (2021), using perforated garden hoes and shadow-play, he exclaims, “soy uno de los otros” (“I am one of the others”). A blunter message is sent with an installation using cowboy hats—a staple in his practice—and mannequin hands with a sign that reads “Joto, ¡¿y qué?!” (Faggot, and what?) (2020), making this piece in particular a perfect example of the power of words, which can also be brutal and painful.

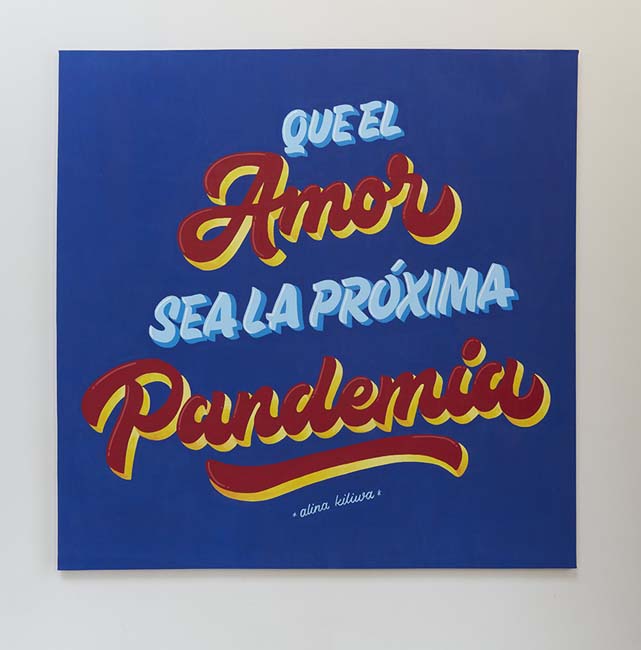

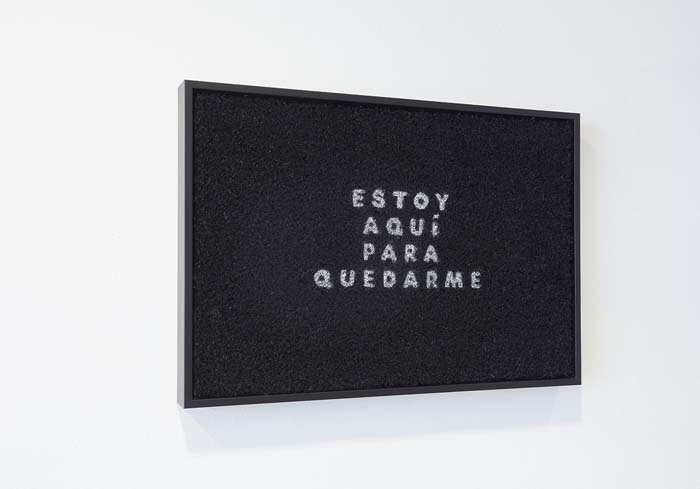

Other works in the exhibition contemplate immigration and police brutality, balanced by artwork that aims to propagate uplifting messages, such as Mexico City’s Alina Kiliwa, who, using traditional rotulista practices, created two commissioned signs that allude to human connection after the pandemic and as an homage to the classic sign-painting practice that is endangered by modern design technology. Perhaps what truly brings the exhibition together is Nery Gabriel Lemus’s welcome mat that reads “Estoy Aquí Para Quedarme” (I am here to stay) (2018). Hopefully, this creative mantra foresees the permanence of artists’ roles as agents of change.