Hammer Museum, UCLA, Los Angeles

September 15 – December 31, 2017

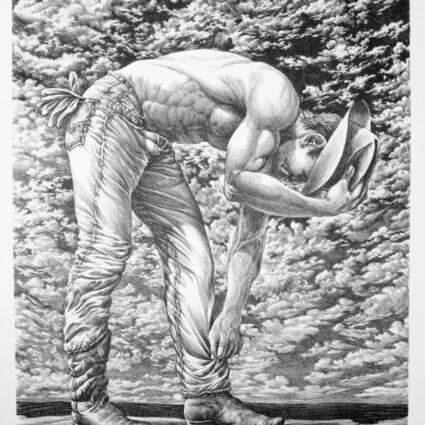

Some advice before visiting the Hammer Museum to view Radical Women: make sure you have a few hours, and bring a notebook and pen. The exhibition, a dense and sprawling display of hundreds of works, deserves focused attention, and there will be many artists that most viewers, unless they have studied twentieth-century Latin American art, will not recognize. But that is the point: this exhibition seeks to fill a major lacuna in the history of art, an absence that points directly to the patriarchal nature of the discipline of art history itself. This is, of course, the gap occupied by hundreds of Latin American and Latina and Chicana women who were working artists in the twentieth century, and who still practice today. Taken in this context, the 120 artists represented in Radical Women are, in fact, only a modest sampling.

Curators Cecilia Fajardo-Hill and Andrea Giunta spent seven years conducting archival research, interviewing artists, and locating and surveying artworks for this exhibition. After amassing a formidable archive of their own, they decided to focus the exhibition only on the years 1960-1985, a time period that encompasses both a key period in the history of art and a particularly tumultuous era in the political history of many of the countries represented in the show. A massive and detailed timeline helps to guide viewers toward a context for the work. This history reflects dictatorships and protests, the slow and violent process of gaining basic human rights and overthrowing governments across Central and South America. For countries in which provisional human rights were not guaranteed, the women’s movement, as we in the U.S. might think of it, often had no analogues, no organized coalitions of women lobbying for child care or reproductive rights. Instead, Latin American and Latina and Chicana women employed a visual language to call attention to an array of injustices perpetrated by totalitarian regimes. At first glance, much of their work shares affinities with American pop or conceptual art, but in context, it points to deeper societal rifts. For instance, Brazilian artist Carmela Gross’s 1968 sculpture of a slab of ham looks a lot like one of Claes Oldenburg’s soft sculptures of scaled-up commercial products, but Gross’s title, Presunto (Ham [slang for corpse]), expediently dissuades such a simple interpretation. Suddenly the ironic pop idioms of the 1960s are an inadequate means for understanding Gross’s practice, which occurred during the Brazilian dictatorship, when dead bodies routinely appeared in the streets. And this is true over and over again in Radical Women; the revelation of this exhibition is a two-way street. We now have access to the work of these 120 women artists who all deserve further study. The heightened analysis and visibility of their work that this exhibition promises will enable art historians and viewers to complicate, and in some cases disavow, their preconceived notions about what artistic production during the years 1960-1985 really entailed.