Teresa Hubbard and Alexander Birchler’s colossal new video installation, Past Deposits from a Future Yet to Come, dramatically explores the archeological record of Austin’s Waller Creek.

Teresa Hubbard, Alexander Birchler: Past Deposits from a Future Yet to Come

March 2, 2024–March 2029

Moody Amphitheater, Waterloo Park, Austin

An antique bottle, submerged and mottled for a century and beyond, rolls and spins. Cascading, buoyant, it flows and falls in massive scale through a zone of imagery some sixteen feet tall and 120 feet wide. In a moment, it seems like a whale, shifting its heft in the ocean’s embrace. In another, an iridescent treasure of sparkle and decay, teeming with wonder, mystery, and watery song. Tossed across time from some distant evening’s revel in forgotten taverns of Austin’s Waller Creek.

Dozens, hundreds, of such objects—marbles, buttons, coins, keys, fragments of china and glass, jewelry, and more—appear in the dancing waterfall parade of Past Deposits from a Future Yet to Come, a colossal video installation by the artist team of Teresa Hubbard and Alexander Birchler. The twenty-seven-minute piece may be seen in the Moody Amphitheater at Austin’s Waterloo Park, on every night that a concert is not being presented, through March 2029. Viewers can download and play Alex Weston’s rich composition for nine pieces (voices, strings, woodwinds, piano), created for the Waterloo artwork, on their own devices.

If a river is a moving collage of image, moment, and thing, then a creek may be more so in micro. Waller Creek rises in the once-northernmost reaches of the city, flowing past the Elisabet Ney Museum and through the University of Texas and Waterloo Park before it joins the Colorado River.

The Waterloo Greenway project, which is re-energizing creek environs from the park to the river, commissioned the work by Hubbard and Birchler as part of a commitment to “showcasing contemporary public art as a starting point for vital community-shaping conversations and collaborations.” The artists, who have worked collaboratively since 1990, describe their film and new media practice as focusing “on the ways in which histories, social life, and memories intersect,” creating “a hybrid form of storytelling that weaves together reconstruction, reenactment, and documentary.”

As they began work on their Waller Creek project, the artists learned that a collection of artifacts from the creek, dating roughly from the mid-19th century to the mid-20th century, slumbered in storage at the university’s Texas Archeological Research Laboratory. Gathered during an excavation earlier in this century, the artifacts include the usual cultural relics with a few delightful, quirky surprises. In Past Deposits, they both embody and transcend their daily associations. Their color, tone, shape, and symbolic meaning heightened and enlarged, they become components of a dense and stirring drama as they slide, spin, and cavort from the top of the image space to the bottom.

The egalitarian nature of the objects and the exalted mode of their presentation encourage that symbolic meaning to be individualized and fluid. Their procession forms a kind of cosmic chess-game ballet, with all the figures performing on the same team. One reads the work as a sweeping saga of a culture charting its unknown future with aleatory, yet revelatory, clues from its past.

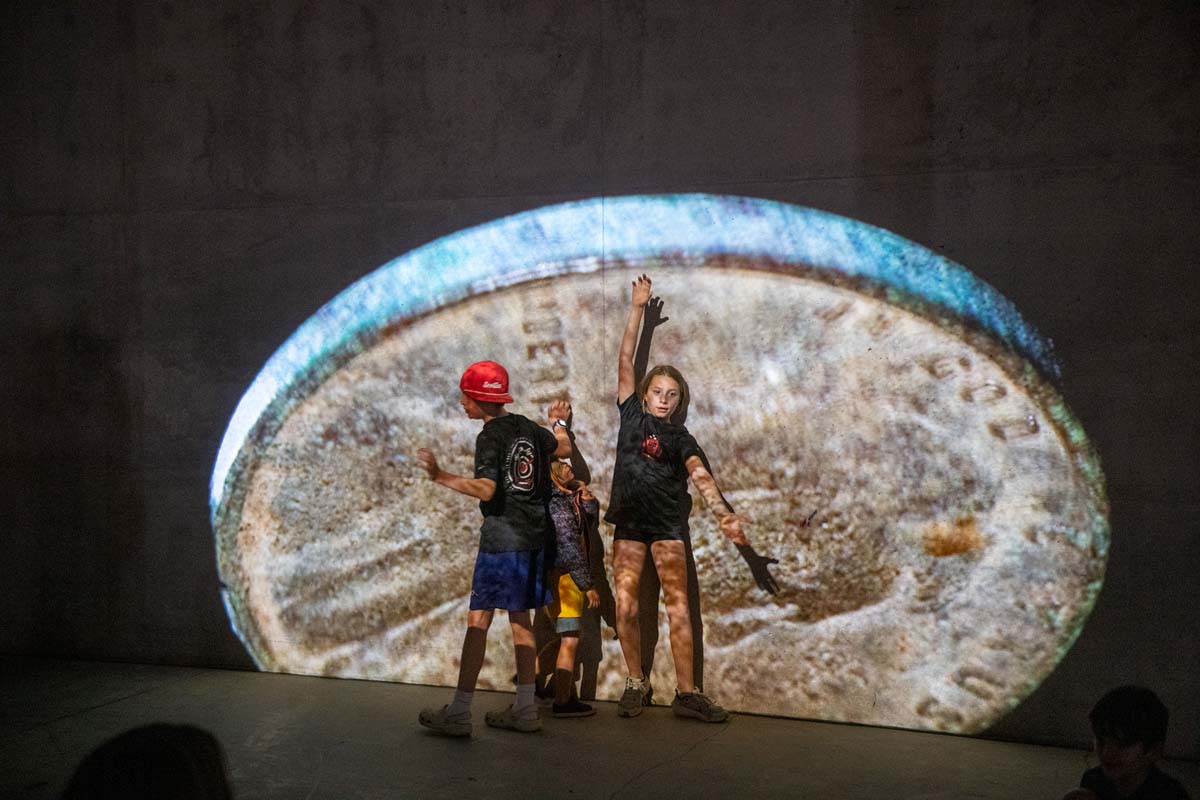

One could also say that the piece proceeds in acts or movements, sprinkled with brief transitional interludes. The first item that peeps onto the top of the massive image field, making passage to the bottom, is a penny. Accompanied by staccato plucked strings and the first vocal iteration of the recurring melodic theme (sans lyrics), the coin floats and revolves, the performance of its weathered patina serving as a prologue for the creek-burst of artifacts to come.

One movement expounds on a glorious array of rust. Horseshoes, a crusted light bulb, ancient keys, inscrutable geegaws, each accoutred with a curiously soothing, burnished corrosion. Chemical processes affecting two religious medals and an unidentified piece of hardware in the set have provided the relics with patches of that bluish-green-turquoise shade one finds in pre-Columbian objects.

Suites of blue, green, amber, and red glass artifacts whirl across the vast proscenium. Their immense close-ups reveal enchanting, translucent surfaces that offer portals into unknown worlds. A playful interchange of flute and clarinet sets a mood for the dancing descent of frog and rabbit figurines.

Marbles appear as planets orbiting through some parallel micro galaxy. Fragments of china, combs, rings and earrings, fugitive buttons, and other household and personal items speak of imagined lives and the ghostly presences that once inhabited them. We ponder who these people were and how they came to surrender these souvenirs of their time on earth. Anonymous heirlooms, they ooze upon the image field as random yet carefully selected signifiers of time and place.

While the musical score accentuates the stories suggested by the choreography of objects in manners both grand and particular, it’s also fitting to experience the piece accompanied by the sounds of Waterloo Park, the hum of nearby office buildings and the grumbling white noise of traffic from Interstate 35. “We always envisioned that Past Deposits can be experienced both ways,” Hubbard says, “as the urban sounds and sounds in the park are also a soundtrack.”

If you attend a presentation of the piece—it’s running for five years—I do recommend experiencing it with the score if you can. When Past Deposits premiered, with a live performance of the music, this past March, some 1,000 people were in attendance. “It was amazing to watch kids and adults running up to the stage to dance and ‘catch’ the objects,” adds Hubbard. A live reprise of the score is planned at least once each year.