Southwest artists Eric J. García, Jack Malotte, Jerrel Singer, Chip Thomas, and Mallery Quetawki reflect on the use of positivity in their anti-nuclear art.

For the last eight decades, the nuclear weapons industry has caused tremendous harm to many communities in the Southwest. In particular, nuclear test downwinders, uranium miners, and those living in proximity to uranium mines witnessed their land desecrated and contaminated, and their communities devastated by disease.

Artists across the Southwest, especially in Nevada, began responding early on; others, only recently. I spoke with several of them, some old hands, and some new to the game.

All The Pretty Mushroom Clouds

I first met Chicano artist Eric J. García at a downwinders’ protest in the middle of the desert. He was standing just outside White Sands Missile Range with his wife, Amanda Cortes. He carried Sixto, their toddler, on his back, and in his hand a cardboard poster that read “Atomic Dumb.” Twenty or so other protesters lined the tarmac, and two state trooper’s cars watched from across the road lest anyone with a poster or flyer cross the cattle guard that separated public from military land.

A few miles away was the Trinity Site, where the atomic bomb was born on July 16, 1945—three weeks before the U.S. dropped Little Boy on Hiroshima and Fat Man on Nagasaki. The local population in New Mexico was left in the dark, and for decades

not many linked the growing number of cancers in the region to Trinity’s radioactive, plutonium-heavy fallout. For weeks and months following the Trinity bomb, locals ate contaminated produce, and drank contaminated water from their cisterns, and contaminated milk from local cows. When ingested, plutonium lodges itself in the liver and bones, releases alpha radiation, and shows up years later as cancer.

García told me he learned about the atomic bomb as a child—albeit a glorified version of it. “I understood the effects [the bomb] had when it was dropped on Japan,” García said. “But I don’t think I really understood the negative effects that the [Trinity bomb] test had on New Mexico.”

García, an Air Force veteran and artist, was a 2021–22 artist-in-residence at the RAiR Foundation in Roswell, New Mexico. His work is political, and García uses it to raise awareness of many issues, among them weapons of mass destruction. As a student at the University of New Mexico, he contributed editorial cartoons for the Daily Lobo, many of which spoke against nuclear waste dumping. One such early cartoon, from 2005, shows Uncle Sam as he buries nuclear weapons by the truckload in the desert, saying, “This way, I kill two birds with one stone: hide all this toxic stuff and hopefully poison that ever-growing brown population.”

In a more recent illustration inspired by García’s meeting with Trinity Downwinders this spring, Uncle Sam blows at the Trinity bomb, and pushes its radioactive dust clouds toward a ranch in the desert.

The aim of García’s art is to start the conversation, despite how heavy the topic may be. To lure in his audience, García relies on humor. “The old saying is, ‘You take a bitter pill with a little bit of honey on it,’” he told me. “I have to give you something to make it easier for it to go down.”

In Nevada, artist Jack Malotte attracts an audience to his anti-nuclear drawings, paintings, and murals with what he refers to as “pretty” aesthetics. Malotte, a celebrated artist, is an activist, an enrolled member of the South Fork Band of the Te-Moak Tribe of Western Shoshone, and a descendent of the Washoe Tribe. He joined the anti-nuclear movement in the early 1980s when the United States was still conducting tests in Nevada. Malotte began with political posters, but soon moved to illustrations and paintings; he later toured Europe, too, to give anti-nuclear talks.

Malotte relies heavily on the pretty factor. “So that they [his audience] don’t realize what they’re looking at,” he told me from his home in Duckwater. “And then, they finally see what they’re looking at, and kind of realize what was going on. I try to be real subtle about it.” But unlike other artists contemporary to Malotte who are much more direct in their representation of the impact of nuclear power—such as artist Robert Beckmann from Las Vegas, Nevada, with his 1993 series Body of a House—Malotte tries to keep the visuals positive. “I don’t try and hit people over the head. Or sometimes I do, but mainly I try not to. It’s better that way.”

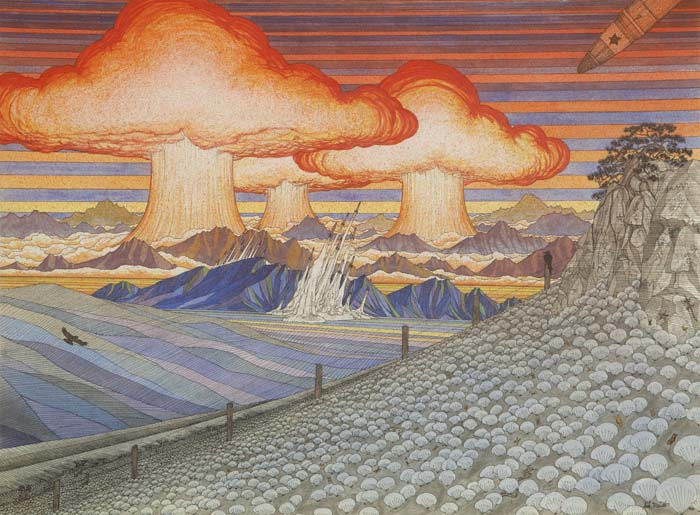

One of Malotte’s favorite anti-nuclear pieces is a 1983 ink and watercolor titled The End, now in the permanent collection at the Nevada Museum of Art. The painting imagines a nuclear world war—three atomic bombs detonate across three valleys, just as a group of nuclear missiles shoot out of the ground—and yet you can’t look away, the way you can’t but gaze in awe at a blazing Southwest sunset. “I try and make it pleasing to look at,” Malotte said in that warm, off- raspy voice of his, always on the verge of laughter, “instead of, you know, always skulls and death.”

All The Pretty Yellow Dirt

Between 1944 and 1986, to fill the U.S. Nuclear Weapons Program’s need for enriched uranium, mining companies extracted close to 30 million tons of uranium ore across the Navajo Nation. Today, some 500 abandoned open-air uranium mines dot the landscape, as do contaminated water sources.

Diné artist Jerrel Singer grew up in Cameron and Gray Mountain, in an area of the Navajo Nation that counts more than 100 abandoned uranium mines. His father, born in the 1940s when the first mines were being excavated, was a rancher and rodeo rider, and instilled in his son a strong work ethic. He died in 1997 of colon cancer, one of the three most common cancers in the Navajo Nation linked to prolonged exposure to uranium or ingestion of uranium-contaminated water or food. Singer added that other members of his family passed away from cancer, too.

Seven years ago, Singer began using his art to raise awareness of social and environmental issues that affect his community, including uranium mining. Not unlike García and Malotte, who also paint murals to engage people in urgent discussions, Singer, too, favors public art. “A lot of people are visual people,” Singer said. “When they see art on a building, they want to ask you questions. ‘What does that mean? Why is that there?’”

This is also how he met artist, activist, and physician Chip Thomas, aka Jetsonorama, who works at a clinic on the Navajo Nation. Thomas is behind the Painted Desert Project, a series of socially minded murals across Diné Bikéyah. Many of Thomas’s patients have been gravely affected by uranium, and several of his murals speak of the effects of uranium extraction on the Diné population. But, as he told me from his house in Flagstaff, when he illustrates uranium contamination on roadside stands, water tanks, or abandoned gas stations, he does so first and foremost to empower his local audience. “I try to reflect back to the people in the community where I work,” he said, “the beauty that they’ve shared with me over the past thirty-five years.”

Thomas’s murals not only opened a new avenue for discussion for Singer—like a billboard, almost—but also inspired a collaboration between the two artists. Thomas and Singer decided on a group of four abandoned gas station tanks near Gray Mountain. Singer painted them dark gray, and added a fuchsia nuclear mushroom cloud that now spreads across all four. The inscription—a quote by the late Santee Dakota activist and poet John Trudell—in large, white letters no one can miss, is unequivocal: “Are they not waging nuclear war when the miners die from cancer from mining the uranium?”

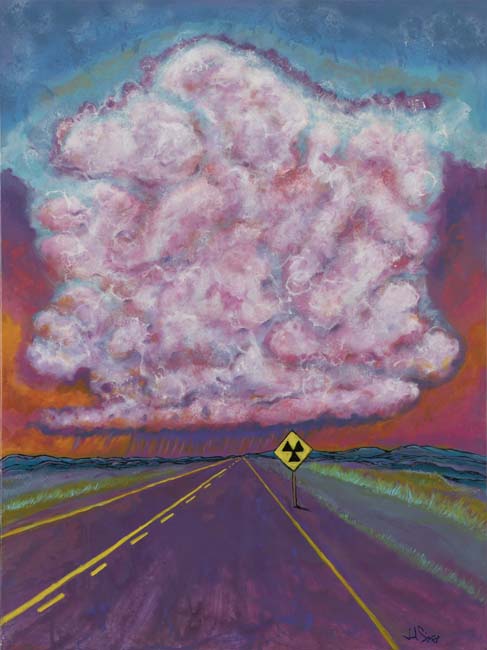

Another one of Singer’s anti-uranium pieces, a painting titled A Warning Ahead (circa 2017), is part of the travelling exhibition Exposure: Native Art and Political Ecology, recently on view at the IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and now on its way to the Marshall M. Fredericks Sculpture Museum in Saginaw, Michigan. In it, the sky is an explosion of clouds, rain, and colors—crimson, orange, blue, green. The only thing yellow, however—perhaps reminiscent of uranium, often referred to as “yellow dirt”—is manmade: yellow lane markings down a two-lane road, and a trefoil road sign, the international warning symbol for radiation.

Mallery Quetawki, a Zuni artist, is the current artist-in-residence with the community environmental health program at the University of New Mexico College of Pharmacy. She uses her art to warn and empower uranium-affected Native communities, from the Laguna Pueblo to the Crow Nation in Montana, and help them understand the danger uranium represents to their health, and the science behind it.

The first piece I encountered by Quetawki, a diptych painting titled Extraction & Remediation (2020), hung across the room from Singer’s Warning Ahead at MoCNA. Her diptych is utilitarian, meaning its function is its priority, as is almost all the work Quetawki creates these days—all in view of translating, as she puts it, the science behind radioactive contamination, damage to the human DNA, and cancer. Her artwork is backed by research, a consortium of physicians and scientists, and her rich understanding of other Native cultures.

And yet, like García, Malotte, Singer, and Thomas, she, too, adds positivity—and beauty, always beauty—to her pieces, to enable her audience to approach the topic from a safe angle. Her aim is to leave viewers with a feeling of strength rather than hopelessness.

To do so, Quetawki uses universal symbols of power and positivity that members of different Native communities can relate to. “We’re always acknowledging the cosmos, always acknowledging things in nature,” she said, as she sat across the table from me in her studio, surrounded by some twenty of her paintings. “My designs have to come from an area of positivity, because when we interact with tribal communities, we can’t just come out and be like, ‘Hey, you guys are sick, you might be dying.’”

We All Are

That morning in April when I met him, Eric J. García and his family were there to support and demand justice for the victims of the radioactive fallout from the Trinity bomb. The three posters his family carried—including one that said “Babies, not bombs,” which he and his wife had attached to the back of their baby carrier—looked like they belonged in one of García’s political comics. They were, for sure, some of the most professional-looking protest posters I’ve ever encountered.

That day, García thought he was protesting on behalf of other people. A few days later, however, after having seen a map of the radioactive fallout from Trinity, he realized that he too, was a Trinity Downwinder. His family is from Torrance County, once a pinto bean capital, just north of White Sands Military Range. That’s directly on the path of Trinity’s fallout.

“My grandpa Fidel, he died of cancer,” García told me. “My oldest uncle, my dad’s oldest brother, he died of cancer. My uncle Abe, my dad, my uncle Milton. There’s been a long line of cancers in my family. And I never thought anything of it other than it was just bad luck.” Here, García paused. “But now that I look at this map, there has to be some kind of connection there.”