Salt Lake City–based artist Carol Sogard obsessively collects and catalogues the remains of a world in crisis, wherein action, if not optimism, may be an obligation.

Salt Lake City, Utah / carolsogard.com / @carolsogard

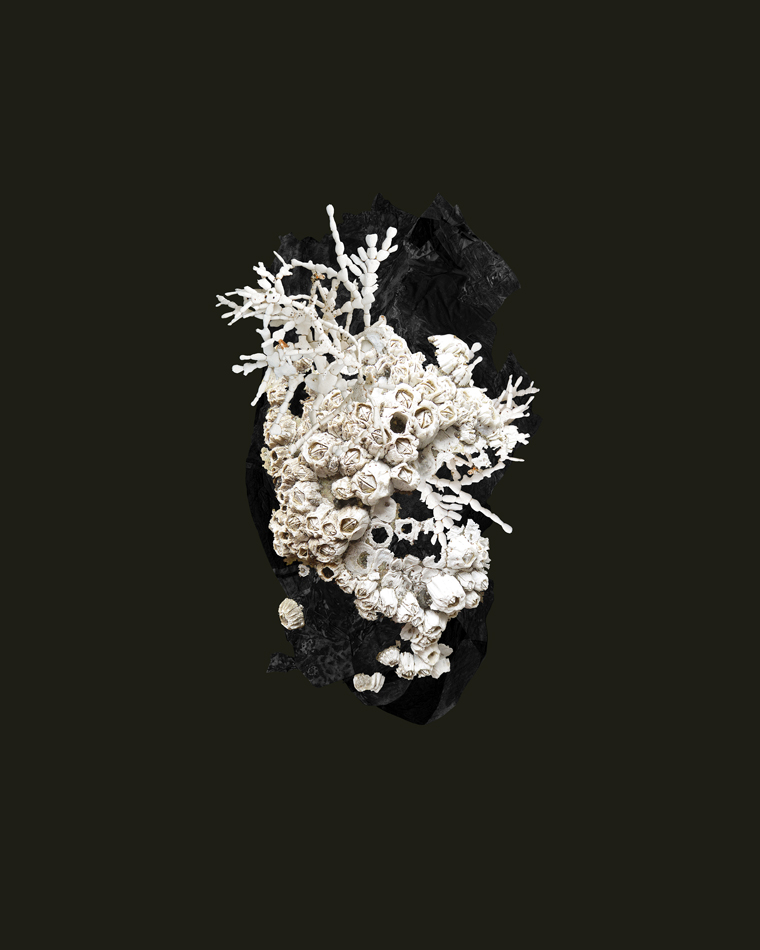

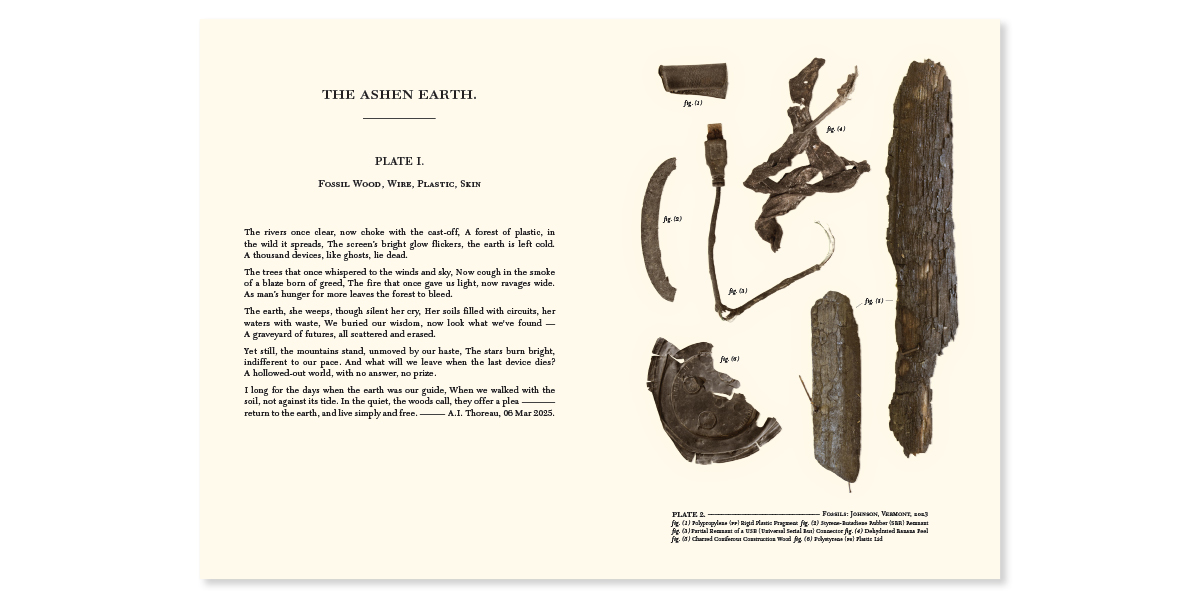

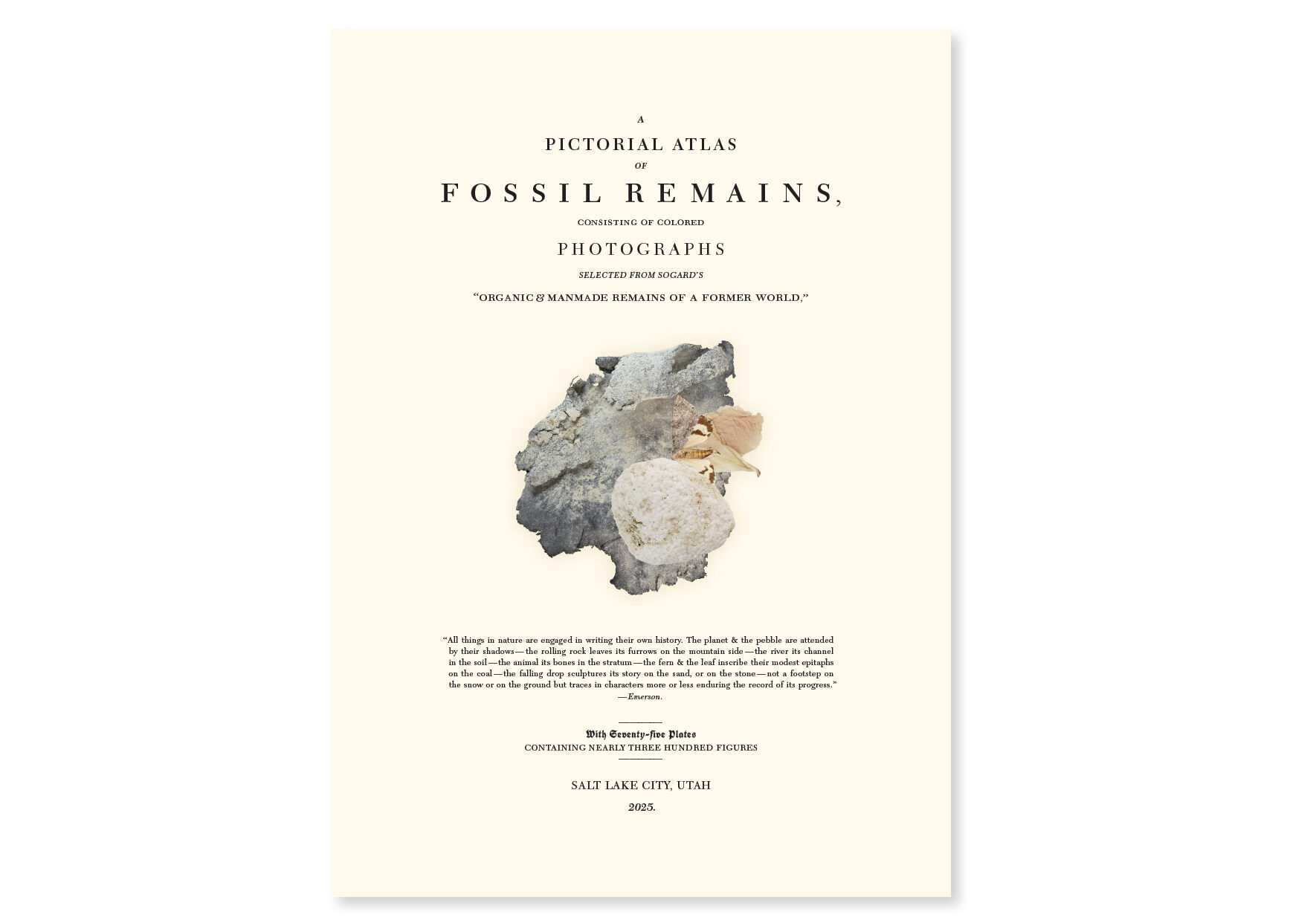

Carol Sogard begins at the end. In recent work, the Salt Lake City–based artist takes “the eternal artifacts of our modern world,” largely plastic detritus, that is, and catalogues them side by side with driftwood, seaweed, bits of conifer, and other remnants of the natural world in a mock atlas of paleontology that feels a lot more like an atlas of eschatology, or the study of the end times. These pages (which are part of a larger project) plate and name our “consumption habits,” as Sogard calls them, sending viewers on a journey through desperate territory: a grim imagined future and a destructive present.

This cycle of work is based on James Parkinson’s early-1800s, three-volume text Organic Remains of a Former World, which examined the fossilized remains of plants and animals. Sogard’s edition of the book archives manmade remains with the organic, taking the concept and modernizing it. Peering in at a two-page spread titled “The Ashen Earth,” a chalky polystyrene coffee lid split by time is plated alongside a charred USB cable and a desiccated banana peel. The facing page features a lyric poem, cryptically attributed to “A.I. Thoreau,” that laments: “We buried our wisdom.”

Just as we’re mentally time-traveling to the future on an apology tour to justify ourselves to future generations, the title page reminds us of something important—the book’s publication information: Salt Lake City, Utah, 2025. Sogard’s work is deeply of the moment, obsessively collecting and cataloguing the remains of this world—one in perpetual crisis, wherein action, if not optimism, may be an obligation.

The phrasing “remains of a former world” evokes the finish—the finish of humanity, or at least the way many of us currently live. The work brings the appropriate gravity to our ecological predicament. But while we’re imagining the future, can we imagine changing the contents of these pages? Sogard’s intention is to inspire viewers “to consider how human behavior dramatically impacts [the natural world].” Importantly, Sogard asks us to do so from the perspective of a future generation, paging through a book of insensible artifacts. It’s this shift of the window of discourse that makes Sogard’s work so poignant.