In Interference Patterns at SITE Santa Fe, Nicholas Galanin (Lingít/Unangax̂) stokes rage and reckoning with the dark history and continuing legacies of settler-colonialism.

Nicholas Galanin: Interference Patterns

October 6, 2023–February 5, 2024

SITE Santa Fe

On November 3, artists Nicholas Galanin (Lingít/Unangax̂) and Merritt Johnson called for the removal of their work from the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. They withdrew the collaborative sculpture Creation with her Children (2017), which addresses “survival, resistance against colonization, the importance of continuum and connection to Land,” from an exhibition of contemporary Indigenous art curated by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith in protest of the “U.S. government funding of Israel’s military assault and genocide against the Palestinian people,” they wrote in a statement on Instagram.

My reading and experience of Galanin’s exhibition Interference Patterns at SITE Santa Fe is very much influenced by what is happening right now in Gaza. Is this fair? Yes, it is. Galanin’s exhibition, which has not received nearly enough critical attention, is a prime example of the power of art to hold up a mirror so that we might see a true reflection of reality in parallel.

Galanin’s deft conceptual gestures reveal seething truths and historical (and current) inequities, delivered with wit and striking accuracy. Specifically, his work “challeng[es] the legacies and consequences of colonization and occupation” from an Indigenous perspective. The parallels between the colonization and resistance of Indigenous Americans and that of Palestinians are quite clear.

Galanin packs a real ideological punch with often minimal gestures. A number of works employ porcelain as a material, in the shape of weapons and patterned with delicate floral motifs reflecting colonial tastes. These axes and hatchets would shatter if used for the function their form implies, representing the condition in which Indigenous resistance, representation, and sovereignty are allowed only in fragile and decorative ways.

Animal skins of polar bear, otter, deer, and wolf appear, some of them reclaimed “trophies,” repurposed as symbolic forms: a “welcome” mat, a white flag of surrender, a star map. Each of Galanin’s works expresses complex ideas about the theft and exploitation—and also the resilience and strength—of Indigenous land, culture, and kin through careful choices in material, image, title, and display.

Consider a grouping of three works that makes clear the holistic centrality of land to the fate and future of Indigenous peoples, and zeroes in on the dissonance that occurs under occupation. Two works here are photographic representations of public artworks—the phrase “Indian Land” spelled out in white letters over a desert landscape, and the word “LAND” crafted from steel “diverted” from the border wall—that borrow the visual language of recognizable landmarks such as the Hollywood sign and Robert Indiana’s LOVE (1966-99) while poking at the facetiousness of empty land acknowledgments and the imposed illusion of borders.

Pointedly, both of those works could be installed virtually anywhere to the same great effect, testifying to the fact, as Galanin notes, that “Land is sovereign in itself.”

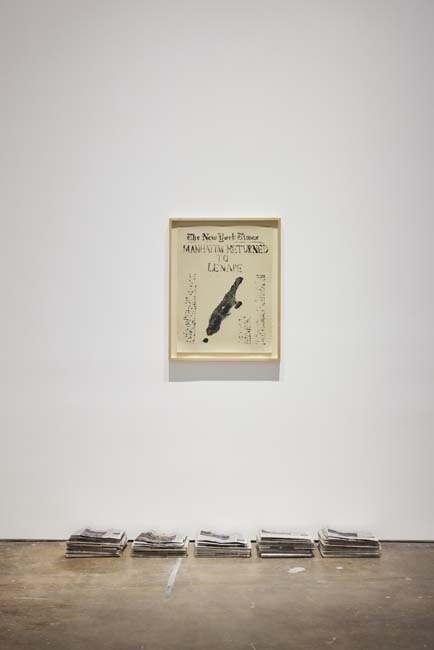

World Clock (2022) envisions the future of the land by realizing Land Back claims in a monoprint of a hand-drawn New York Times front page with the headline “Manhattan Returned to Lenape,” while pricking at the “perceived impossibility of such an event.” On the floor under the print lie stacks of recent issues of the Times, accumulating as if in waiting for this event to eventually come true, while, instead, chronicling the brutal mass murder of another Indigenous people in its pages.

Galanin bears witness to the dark history of residential boarding schools as well as the strategies of survival practiced by Indigenous people. Loom (2022), an eight-foot-tall totem pole-like form with Lingít formlines built of wooden children’s desks and chairs, stands for resistance to assimilation and preservation of culture despite the calculated cultural and linguistic extermination attempts enacted by the U.S. and Canada under the guise of “education.” A pair of child’s handcuffs appears under a spotlight, a grim testament to the physical reality of the forced removal of Indigenous children from their families.

But in a gesture of hope, a monumental video projection, k’idéin yéi jeené (You’re doing such a good job) (2023), counters these dark artifacts with the sweet and sunny face of Galanin’s own child, beaming in response to his father’s phrases of love and encouragement issued in his native tongue. The enunciation of the words in a language colonizers tried to steal, as Galanin writes, serves as a “disruption of settler-states built on genocide.” If you, like me, have recently been inundated with a steady stream of images of children covered in ash and blood and wrapped in shrouds, you will find this room, with its tension between loving care and absolute horror, hard to bear.

Other works deal with the treatment of artifacts, the complicity of museums in cultural erasure, and the misplaced sentiments of reverence toward Native culture along with efforts to contain and delimit it. In Infinite Weight (2022), a taxidermied wolf appears unmoving in a time-lapse video of the landscape of the artist’s homeland in Alaska, while the same wolf hangs upside down from the gallery ceiling. In Galanin’s words, the wolf is “trapped within the frame of a video loop” and also “marginalized to exist only on the ceiling.” The wolf stands as itself, a creature hunted to near extinction by settlers unsettled by the predator, but also romanticized—as long as the animal is contained. Under “anthropocentric capitalism,” Galanin asserts, the wolf has value only as a symbol, frozen in time, defanged.

The wolf also stands for “all life determined less-than-valuable, critiquing the practice of devaluing and destroying life in favor of control and artifice,” Galanin writes. The wolf is a reminder that, throughout history, acts of violence aimed at settler communities and property—whether the wolf pack or the raiding party, acts of “savagery” or “terrorism”—have been used as justification for extermination, for genocide.

But it’s Neon American Anthem (red) (2023) that is the crux of the exhibition. The words “I’ve composed a new American national anthem / Take a knee / and scream / until / you can’t breathe,” bristle in all-capped red neon lettering buzzing against a black wall. There are mats on the floor, where viewers are invited to participate in “an intersectional space for catharsis: to mourn the loss of lives, freedoms, and safety for people and Lands subjected to American violence, and to protest continuing oppression.”

Unlike Yoko Ono’s Voice Piece for Soprano (1961), a score in which participants are invited to ”Scream. 1. against the wind 2. against the wall 3. against the sky,” Galanin’s scream piece has a discernible, direct object: the United States of America. The invitation to “take a knee” recalls the NFL protests against police brutality. The scream is offered as a way to give form to all of your pent-up rage and let it come loose from your body. Until, like George Floyd, you can’t breathe.

The rage is easy to find. The rage against a country that has been at war for all but seventeen of its 247 years, with nearly half of those wars waged against the Indigenous peoples of this continent. The rage against extraction economies, ecocide, and extinctions. The rage against normalization, complacency, and apathy around all of these things.

The rage is easy to find, but it is hard to muster. The silence of a museum space, that calm space of quiet contemplation. It is difficult, to say the least, to find the courage to disturb that. To break that silence. That very difficulty demonstrates the power institutions of control hold over us.

It was when I dropped to my knees that it hit me. The painful sensation of the rough mat piercing my knees sent the scream bolting out of my body.

Did it feel cathartic? No. I didn’t feel better after letting loose in the gallery. Because my scream accomplished nothing. If anything, I felt more enraged.

Neon American Anthem (red), in its call for raw emotionality, stands in stark contrast to the cool conceptualism of the rest of Galanin’s work. But its implications are clear. As one commenter on an Instagram post about residential schools put it, “The U.S. doesn’t want a reckoning for its sins against the Native Americans because this place would burn to the ground with screams.”

As Americans, Galanin asks us to choose our national anthem. Is it a scream? Or silence?

Courtesy the artist and Peter Blum Gallery, New York. SITE Santa Fe commission with the support of Peter Blum Gallery and Becky Gochman.