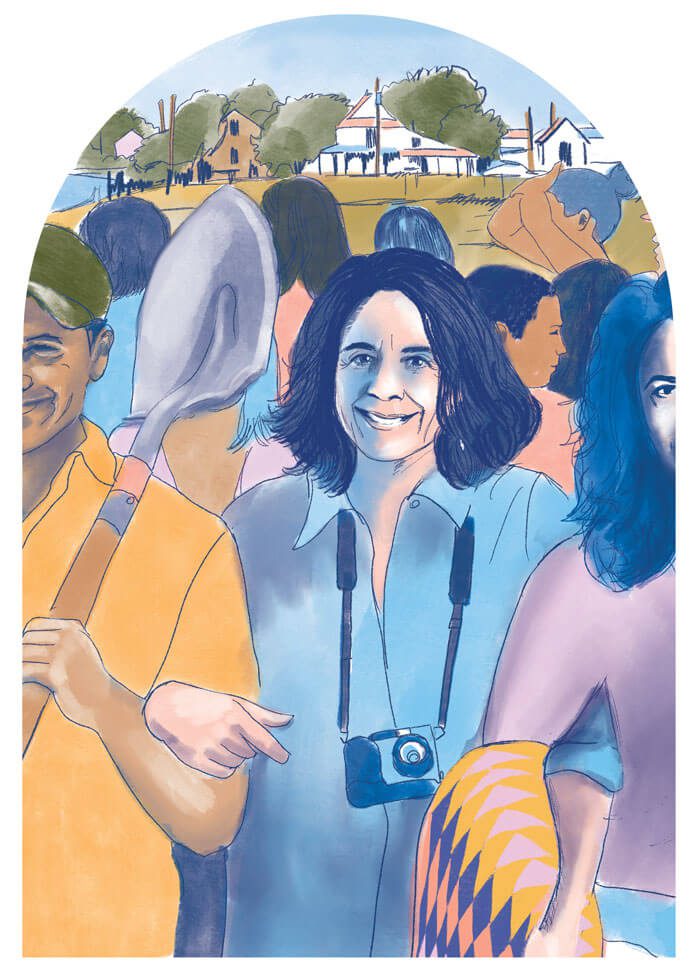

Name: Maria Varela

Born: 1940, Newell, PA

Lives: New Mexico

role: Organizer, writer, photographer

quote: “It’s important to realize that every race and culture has within its DNA the oppressor and the oppressed.”

In her essay, ‘Time to Get Ready,’ Maria Varela recalls, “I once volunteered in the fourth grade that I was Mexican, and the angry response of the teacher frightened and shamed me. ‘No, you are not! We’re all Americans here,’ snapped Sister Rosita.” For a woman who has spent her life fighting white supremacy across the U.S., this scene presents a formative moment. Varela’s activism began when she joined the Young Christian Students organization in high school, which “holds that as Christians our vocation is to be actively engaged in dismantling racism, economic injustice, antidemocratic forces, and unjust wars.” While Varela was organizing Catholic students in the North to support freedom rides and sit-ins in the South in the early 1960s, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) asked her to come to the South and participate. Fears of the violence she might encounter as a woman of color working for integration didn’t stop Varela from boarding a bus to Atlanta, Georgia, and eventually organizing “a literacy project geared toward the twenty-one-question voter registration test required by the State of Alabama.” Mentored by Ella Baker, Varela and the other members of the SNCC learned to listen, “really listen to people at the margins, and respect their knowledge and learning processes… We as book-learned people had to rid ourselves of the notion that we were the educated ones and those at the margins were not.”

We as book-learned people had to rid ourselves of the notion that we were the educated ones and those at the margins were not.

My first question for Varela was how she shifted from working for the Civil Rights Movement in the South in the 1960s to spending the rest of her life working with the Land Grant movement in New Mexico. In my mind, those regions and causes were not directly connected, but for Varela, they were. She was invited to the Convención Nacional de la Alianza Federal de los Pueblos Libres, a “summit of Native American, Mexican American, and African American leaders” in Albuquerque in 1967, a historic meeting of activists, where she photographed Willie Ricks and Ralph Featherstone on horseback, “borrowed gun belts crisscrossing their chests and rifles held high in the air.” Her work in New Mexico began to join writing with photography, and she understood the connection between the black civil rights movement and the land grant movement, both of which were about organizing to resist white supremacy. Her photos document the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign and the Chicano movement.

She writes, “If something was not done to maintain the land and water rights of Mexicanos in the Southwest, then our home lands would be lost just as Native Americans had lost theirs in the last century and African Americans were losing theirs in this century… Within these homelands are the taproots of our cultures where the stories, medicinals, ceremonies, music, dance, and art find their continuation and replenishment. African Americans, Native Americans, and Mexicanos are, at origin, ‘people of the land.’ We have no future in this country or on this continent if we lose our homelands.” Varela moved to a community in northern New Mexico to work full time for La Cooperativa Agrícola and La Clinica del Pueblo, where she has spent the last thirty years to found three non-profit organizations with her neighbors. Facing threats from “federal and state agencies, global mining and timber corporations, real estate agents, resort developers, and environmentalists,” Varela believes in “creating hybrid models,” like Ganados Del Valle/Tierra Wools, a cooperative of sheepherders, weavers, and craftspeople she co-founded in Los Ojos, New Mexico.

Wherever there is oppression, there is resistance…People always resist.

These days, Varela is excited about the young adults who are drawing lessons from the SNCC. “Wherever there is oppression, there is resistance,” she told me, a lesson drilled into her by Baker. While she is most fearful of the rise of authoritarianism, “especially in this country,” she remains hopeful about the movements for social justice and resistance. “People always resist,” she said.

To learn more about Maria Varela and her work, see Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC, University of Illinois Press, 2010.