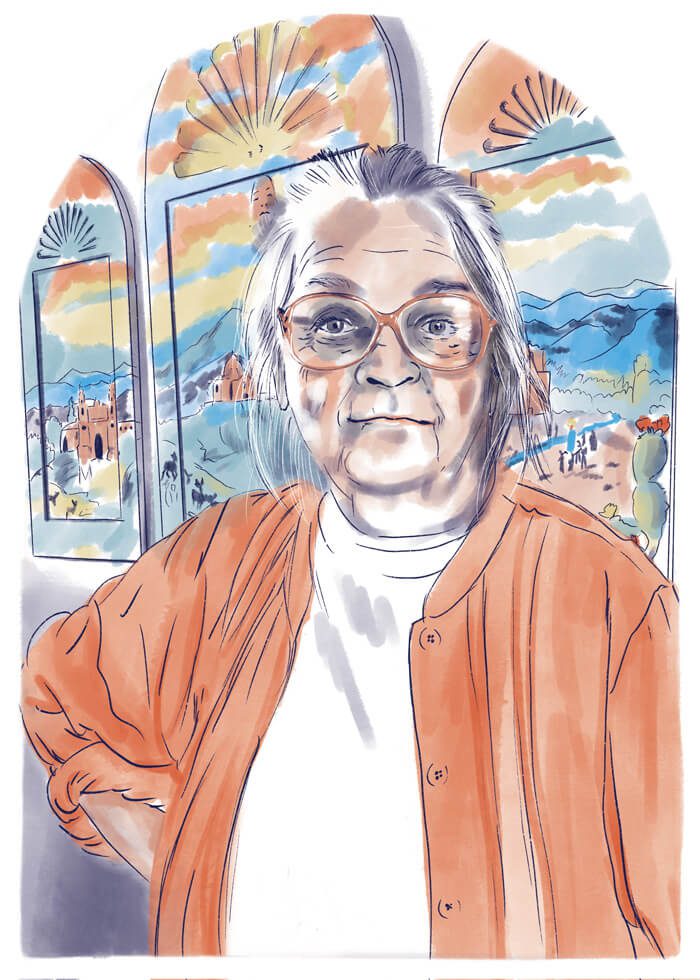

Anita Rodriguez is a true renaissance woman. She is a writer and painter, in addition to her accomplishments in the field of sustainable architecture. She invited me one day in January to her handmade Taos Valley home to see her work in person. I drove up the day after a snowstorm, and the Taos mountains were blanketed, creating a picturesque backdrop to Rodriguez’s exquisite home and hospitality. We settled down at her kitchen table with hot mugs of tea and she began to tell me of the enjarradoras, or women adobe builders, of New Mexico.

The contributions of women to the field of adobe architecture have largely been overlooked by historians, something that Rodriguez is trying to reverse.

Rodriguez’s roots reach back over three hundred years in New Mexico. She was born into an oral tradition and culture in which adobe building was a keystone. Adobe architecture is not only sustainable, it helps to strengthen communities through shared labor. Rodriguez explained, “The energy that adobe uses is human, and that means jobs.” Women in New Mexico villages built the fireplaces and were responsible for all finishing work, which included the building of bancos, plastering, and any details that personalized the home. The contributions of women to the field of adobe architecture have largely been overlooked by historians, something that Rodriguez is trying to reverse. When she became serious about learning the art of adobe, she traveled from village to village with a tape recorder and video camera, talking to the remaining enjarradoras, from whom she learned to build adobe while simultaneously preserving history.

Culture and history are inseparable from architecture for Rodriguez. She is committed to empowering communities in northern New Mexico and recognizes the effects of historical trauma. She said, “About fifty percent of the New Mexico populations are historically traumatized people who have suffered for generations and experienced enormous loss.” Rodriguez has a deep understanding of history and spoke about the consequences of the Mexican-American war, for example, and the intense racism that followed the U.S. land-grab of more than half of Mexico’s territory. The conflict resulted in a loss of land for many people and the ripple effect of this loss still impacts many communities today. The Land of Enchantment has layer upon layer of complicated history, some of which has been co-opted to create a less complex, more romantic image of the place.

Adobe defines New Mexico in so many ways, and yet adobe building is a disappearing art. When Rodriguez was growing up, Taos was still a “mud town,” as she described. Since those days, Santa Fe Style has proliferated—though, the original, sustainable construction methods have not. One of Rodriguez’s primary concerns is the stewardship of the Earth; through her methods of construction, one could potentially build a home by utilizing the contents of a backyard. “See that white color there?” she asked, pointing to a wall adjacent to the kitchen table. “It is painted with white dirt from down the road. Every time I need to touch it up, I can take a spoon and go down there to dig some up.” Which illuminates the potential cost of adobe construction versus mainstream building. Rodriguez elaborated, “If I wanted to repaint this house, you’d have to take into consideration the cost of manufacturing the paint, transporting the paint, the disposal of everything, all of the costs of the industry. Adobe architecture is here—it’s dirt.”

See that white color there? It is painted with white dirt from down the road. Every time I need to touch it up, I can take a spoon and go down there to dig some up.

The word “sustainability” summons many ideas and images, such as reusable straws and water bottles. For something to be truly sustainable, it must be able to serve in the present and decompose in the future. Rodriguez thinks adobe is the building material of the future. “The best thing about adobe is that it melts. What are we going to do with all of the buildings and trailers when we are done with them? This beautiful house will melt back into the earth from which it has risen when it is no longer needed,” she detailed. The sustainability movement could take a page from Rodriguez’s book and look to the past to find solutions for the times to come.

At seventy-eight years old, Rodriguez has no shortage of energy or talent. She has a thriving painting practice, published a book in 2016 (and another is in the works), and developed one of the best-known formulas for waterproofing dirt floors. Adobe building is just one facet of her character, and it would be a shame to define her solely by that work. After our interview, I stayed to look at her paintings—allegorical scenes from history and mythology painted in vivid colors. As she was telling me the stories the pictures contained, she turned to one featuring a woman holding tarot cards and exclaimed, “Aha! I do tarot too! Would you like a reading?” Rodriguez is complex and full of surprises—like this land and its many histories.