A conversation with Arizona artist Nazafarin Lotfi, whose work explores the experience of bodies out of place: how they are historically situated, and what it means to be a contentious body in a contentious landscape.

Balancing personal, political, and aesthetic dimensions, much of Nazafarin Lotfi’s work explores the experience of bodies out of place: how they are historically situated, and what it means to be a contentious body in a contentious landscape. Absorbing early influences from literature, archaeology, landscape imagery, and the perceptual challenge that painting provided to translate three-dimensional space onto a two-dimensional surface, Lotfi’s multidisciplinary approach has evolved through drawing, sculpture, and performance. Her practice is very focused, yet not so overly rigid that it stifles new experiments. Ideas are given space to unfold in multiple projects over time, each their own unique investigation but consistent across thought and intent.

I first got to know Lotfi during a summer at Ox-Bow School of Art, a forested idyll tucked among the eastern sand dunes of Lake Michigan where folks from Chicago and elsewhere flock to teach art, study, or retreat at its residency programs. Some years later, after nearly a decade in Chicago and navigating our respective art trajectories through the typical post-grad school growing pains, we reconnected in Tucson as we’ve found ourselves adjusting our studio practices to working in and beyond the Southwest.

We had initially envisioned a studio visit and desert hike to discuss her recent work and the central concerns of her art practice, but instead opted for a virtual meetup in light of the drastic spike in coronavirus cases in Arizona. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Greg Ruffing: Something we’ve discussed around your art practice is the idea of the horizon—and that particularly here in the Southwest, and in the colonization history of the United States, the horizon is like a marker of progress, but that’s never enough because there’s always a horizon that you see further out.

Nazafarin Lotfi: I think the language of invitation is used in relationship to the horizon and the genre of landscape painting that is inviting the settler to come to this open land. Let’s remember that the landscape painting is a frame, right? We don’t know what is outside of the frame. And because it’s the horizon, it suggests that it’s the expanse, it’s the whole thing—but it’s not. We see it historically in the American Southwest, and European expansion in Africa and the Middle East. Landscape is a symbol of spatial power in some ways. Who gets to go where?

Growing up, I was very interested in landscape painting, particularly in middle school when I was taking art classes with a painter who lived on our block. I found great joy looking at the images of different natural places that I found in her books, and I made colored pencil drawings from them. The images’ ability to transport me to different places was the most amazing thing then. Given the political and social climate of the ’80s and ’90s in Iran, the Iran-Iraq War, and the residues of a failed revolution [Iranian Revolution of 1979], it was a grim time. Looking back, I think it was healing to be able to imagine other places, which opened up new worlds and possibilities for me.

I do think about the horizon a lot—I think about the distance to the horizon. I’m way more interested in what is in between from here to the horizon, the process you have to take to arrive when we know you won’t arrive. It’s like you get to the assumed horizon, and then there’s still a way to go.

Has Tucson had a certain influence on your work that is different than how you were approaching your work in the Midwest?

Yes, and I have realized I’m one of those artists that wherever I go, I’ll reinvent myself. […] I’ve been here the whole Trump presidency, so it’s been four years. That is also something crazy, to move from Chicago after Trump got elected, after the Muslim travel ban went through, to the frontline of this crazy [immigration] mess and to live closer to the border, which I found to be very triggering. While my immigration to the U.S. doesn’t really fit into the local conversation, I identify with it because I have also experienced restrained mobility because of not having the right passport. I know what it means to be separated from a part of your life because of the border. I often think, for us, the border is inside. The emotional and psychological impacts of it will always remain.

But I think I found a focus in Tucson that I didn’t have in Chicago. Moving to a smaller and easier place to live opened up more time and space for me, and that was good for the work. My identity in Chicago was so tied to SAIC [School of the Art Institute of Chicago] and that community, which is really great and I miss a lot of things about it, but being rooted in that way didn’t allow me to break everything and restart—which I think I need to do once in a while.

I get the sense that, at least in your experience in Tucson, you’re pretty active about being out in the landscape, going for hikes, etc. I imagine in one sense it’s leisure or exercise or whatever—but is it also research? Or some way of relating [to the land] and finding material for your work?

Yes, it is all of them. I also like to think when I walk. So I’ve been thinking about this whole [geographical] place being my studio. Everything from picking olives in the yard, to going for walks, identifying birds and plants, collecting rocks, as being part of my studio practice.

There are sometimes direct references to the landscape in my work. I think more and more the surfaces of my work are getting richer. And I find the feelings or experiences of being on this land come with me to the studio. I have done sketches outside and used them as references in the studio, but not in terms of realistic representation. The embodied experience is what I am interested in. […] I have to internalize things and then it comes into the work.

I’m way more interested in what is in between from here to the horizon, the process you have to take to arrive when we know you won’t arrive.

Something I find interesting and also difficult about this place is its complexity as a borderland. For example, when I take a walk close to my studio on the west side at Tucson Mountain Park, the land is pristine and gorgeous and you’re probably going to be the only person in this beautiful canyon—and then the sky is militarized. There are loud fighter jets flying above you. A one-hour drive south from my studio is a national refuge that I go to, and that same area is one of the corridors where a lot of refugees and migrants die in the desert crossing the border. Learning about these realities attached to this place makes the desert less romanticized in a cliche way as it has been socially constructed. Although I do have a romantic relationship with the landscape here because it gives me what the city does not: the feeling of belonging.

Some of the first work of yours that I had seen in Chicago were the boulder pieces you made and were carrying through Washington Park. As objects, they’re really enigmatic. From the way that you worked with those, to some of the more recent sculptures, is there a thread that you’ve been exploring? […] It seems the forms themselves have gone in different directions but I wonder if there’s something you’re still working through with it.

Yes, that’s a great question. I’m not done with those boulders, I’m actually going to make more of them soon. These are all part of the different languages that I’m developing in my practice, and what I like is being able to use them interacting with each other. I see the sculptures as way more figurative than the boulders, and I think [the current sculptures] reference the body—that’s how I’ve been thinking about the body more.

That’s one of the things that happened since I moved to Tucson. It’s been hard to witness what is happening at the border with families being separated. I’ve been going through the same experience with my family, who has never been able to visit me here—they are not allowed to step foot in this country, and this is all so painful.

I’m interested in working with interior spaces and negative spaces, even though it might mean you have to work the exterior. All the sculptures are hollow. The objects that I initially used to make the papier-mâché casts are removed. I’m interested in what we don’t see by emphasizing close observation and activating touch and sight.

I’m actually now working on a body of new sculptural work that explores the intersection of the body and land. Instead of growing upward, the forms fold in on themselves and expand horizontally. When you give up verticality, the figures open up to new worlds—a non-human world. The point of view that is high above is replaced by the one that is looking up instead of looking down.

Is that a way to connect to the site too? Because certainly the landscape is not neutral. And even thinking about Washington Park, it’s a loaded site, and there are potential contestations of these sites, right?

Yes, I was interested in Washington Park because it is literally the border between University of Chicago and neighborhoods [that are] historically African American. I lived in the east side of the neighborhood closer to the campus. I was interested in that area between these two distinctly different realities and experiences. I felt that was the place I’ve been in for so long. I really don’t like the word “in-between” because it suggests some sort of not being sure which one you are, or if you are this or that. I think it’s misleading. Am I Iranian or am I American? The real experience is nuanced and complicated. It has historical context which is not immediately available. Knowing that I occupy a body that is contentious, just like the border.

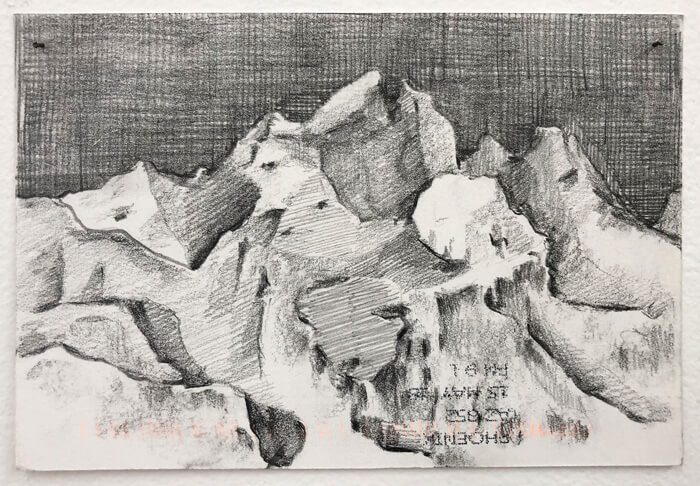

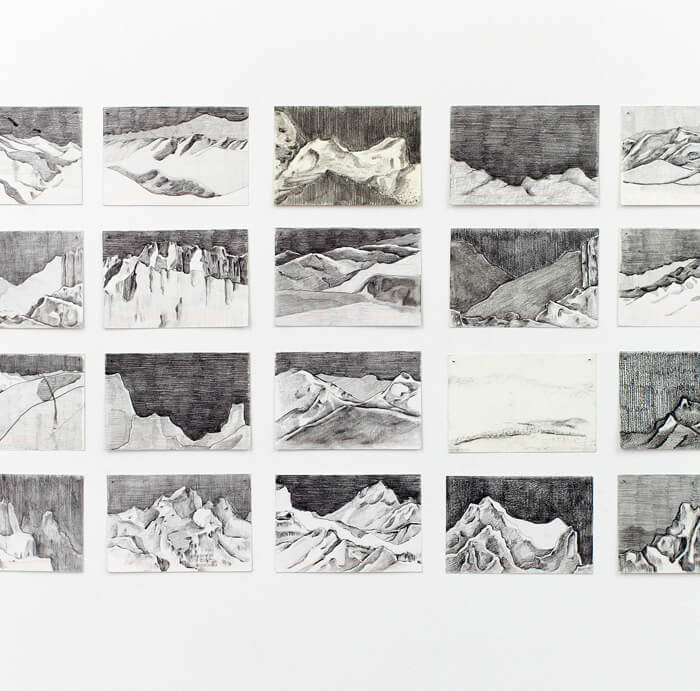

I wanted to also ask about the sculptures and drawings you have in the exhibition at MOCA Tucson [Working From Home, October 3, 2020–March 28, 2021]. The drawings seem like they’re also building upon past painting and drawing work that you’ve done. They feel like they’re very intimate—do they reference a real place, or is it an imagined place? Or some personal space for you?

When I moved here, it was so hot and bright that I couldn’t do anything outside! That’s literally how the drawings started, because then I realized that a lot of my work has to do with my reflection on my environment. I started making these sketches from my walls and windows and thinking about the space inside and the space outside. I think the same idea translated into going on hikes, and in the interior spaces of the sculptures in relation to the space that the objects take up.

Generally in your process of making—and again I think a lot about the sculptures, but also other work too—it seems like there’s a kind of building and layering, and a very iterative approach.

Everything I do is layered. It’s not necessarily by choice, I think it’s just how things feel right to me that sometimes it takes a long time to develop something. The color pencil drawings, there are many, many layers. Similarly, the sculptures there also are multiple painted layers. I like building things, and when you do layering you’re establishing the space. You keep pushing it back. So I think it creates more depth. That’s something I like to create in my work.

I’m also really curious about the brass fountain piece, the shape and the material choice. I know brass is rust-resistant, but I imagine that there’s more to it for you than that.

I’ve been thinking about making a water feature alongside my work since I moved to Tucson, maybe because of the familiarity in architecture. There are places here that remind me of Iran. And then when I started doing a little bit of research, I realized there are traces of Islamic architecture that were brought to the Southwest with the Spanish colonial architecture. And Islamic architecture was deeply inspired or intertwined with Iranian architecture.

I’ve also been looking at Iranian art: how has it been traditionally and historically approaching landscape? And what I learned is that it’s the gardens—it’s not painting, it’s not visual vocabulary. It’s actually creating spaces that mimic the “ideal” landscape, but they’re man-made. They’re designed to create a perfect image of landscape or nature. And the water feature is a very important aspect of it—that you could bring the outside in. That’s exactly what I wanted to do with the museum, to bring the sound of the water that is more associated with the outdoors or the public plaza, to bring it indoors to the gallery.

[…] I think my fascination with the gardens has to do with the construction of utopia too—in my culture, utopia is in the past. The idea of progress that we discussed earlier relates to the future, and since I moved to the U.S. I noticed that it’s a big part of this culture, to be future-oriented and not linger in the past. But then there are certain historical things that will never be forgotten, and become markers of time. And I think the pandemic is going to be one for all of us. Already we are talking about before and after. And I grew up with very, very strong before-and-after culture: “before the revolution” and “after the revolution.”

Lastly, what is 2021 looking like for you?

I’m going to Artpace at the end of January for two months and I am very excited. It’s a residency in San Antonio that provides you with space to live and work, and ends with an exhibition. There’s support for the project and I am looking forward to it. I hope 2021 is a better year for everyone. And I hope to visit my family after four years.