An art world debate over the modernist credentials of iconic Hopi-Tewa potter Nampeyo surfaces tense questions about art, craft, Indigeneity, and the meaning of modernity.

Nampeyo in Paris

Steve Elmore remembers the first time he saw a ceramic vessel by Nampeyo. He was at a Native American trade show sometime in the 1980s when a large golden pot covered with intricate designs caught his eye from across the room. “I said, ‘That looks like Paul Klee, it looks like Miró, it looks like Alexander Calder,’” Elmore recalls. “I went over there and said, ‘Well, who made it?’ They said, ‘Oh, some old Hopi potter.’”

Elmore was surprised to learn that the piece was from the early 20th century, the same era as the European modernists who had sprung into his head. There was something strange and vibrational about its aesthetic that seemed to hum in chorus with the late-19th and early-to-mid-20th-century artistic movement that broke from traditional artistic modes in the midst of the broader modernization of society.

“Part of the obsession [for me] was, ‘Why does it look so modern?’” says Elmore. “Well, it’s because some of the modern artists were influenced by it. If art history has any value, you should be able to trace that line.” The assertion that one of Southwest Pueblo pottery’s most famous figures was an early modern artist isn’t new, but Elmore is probably one of its fiercest living proponents. The position has plunged him into an art world debate that swirls with contemporary questions about art, craft, Indigeneity, and the meaning of modernity.

Elmore is now a veteran ceramics dealer, having transitioned from globetrotting collector to Santa Fe-based gallerist in 1999. He self-published a book about Nampeyo in 2015, a project that earned him a rapscallion reputation in the academic world due to a copyright infringement lawsuit with Harvard University that ended with a settlement.1 In Search of Nampeyo: The Early Years, 1875-1892 examines the Hopi-Tewa potter’s beginnings in the village of Hano as she mastered her craft and began reinterpreting designs from ancient Hopi pottery sherds.

Nampeyo’s Tewa ancestors relocated to Hopi lands (from present-day New Mexico to Arizona) at the conclusion of the Pueblo Revolt of the late 17th century, fleeing Spanish reconquest and bolstering Hopi defenses. The Spanish failed to gain lasting control of Hopi territory, so Hopi-Tewa culture formed a strong, unbroken line when Nampeyo was born atop First Mesa around 1860. In his book, Elmore declares Nampeyo a “child prodigy” after teaming up with her descendant, Rachel Sahmie, to authenticate a pottery collection that may include some of her early work.

Elmore’s narrative culminates just before the artistic leap that would launch Nampeyo to international fame—and form the roots of the Nampeyo-as-modernist thesis. Inspired by a white archaeologist’s abundant findings at the ruins of a Hopi village called Sikyátki, she began creating the richly polychromatic and compositionally complex vessels that characterize her mature style.

Nampeyo’s breakthrough launched a pottery movement known as the Sikyátki Revival, but she pushed far beyond revivalism, constantly honing her craft and evolving her aesthetic. Her work paved the way for a subsequent generation of innovative Pueblo potters such as Maria Martinez of San Ildefonso Pueblo and Margaret Tafoya of Santa Clara Pueblo.

A number of writers have pointed to Nampeyo’s mind-bending spatial plays, which merge multiple angles of birds, butterflies, and other sacred Hopi motifs across a single visual plane, as a possible source of inspiration for Cubism.

The Native art and history scholar Gregory Schaaf, of Northern Cherokee Nation, elegantly describes this approach in his 1996 directory of Hopi-Tewa potters: “A parrot design would sometimes be divided into four quadrants. The curling beak, the flowing wings, and the sharp-tipped tail feathers were rotated in space and then fit back together like a mosaic. The effect is sophisticated and ingenious, like a great Cubist painting.”2

The aesthetic, also known as Hano Polychrome after Nampeyo’s birthplace, proved to be marketable on a global scale. “[Nampeyo’s market] just grows and grows,” says Elmore. “It grows from the tribal market, which is all trade and all local, [to the] collecting expeditions from the Smithsonian that bought 2,500 pieces of pottery in one bite. And then the railroads start arriving with more visitors, more collectors.”

From the late 1880s and onwards, Nampeyo’s work appeared in traveling exhibitions across the United States and Europe—including at the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro in Paris. “Picasso acknowledges that he saw Hopi katsina dolls at the Trocadéro, so why wouldn’t he have seen the Hopi pottery that was there at the same time?” says Elmore. “Picasso is the Nampeyo of Paris.”

Nampeyo at the Museum

When Diane Dittemore hears Nampeyo and Picasso’s names in the same sentence, she’s quick to express wariness. Dittemore is in her forty-fifth year as the associate curator of ethnology at Tucson’s Arizona State Museum. She’s in the midst of updating an online Nampeyo exhibition3 that she originally curated in 2000, and doesn’t plan on mentioning modernism in the new didactics.

“I get a little bit impatient when there’s talk of trying to put Nampeyo into a larger art historical canon with Western values and worldviews,” says Dittemore. “It’s a box that is so divorced from any kind of traditions within Hopi. This might sound snarky, but sometimes I get the feeling that some of these writers are more interested in impressing people with how worldly they are, with their encyclopedic knowledge of Western art.”

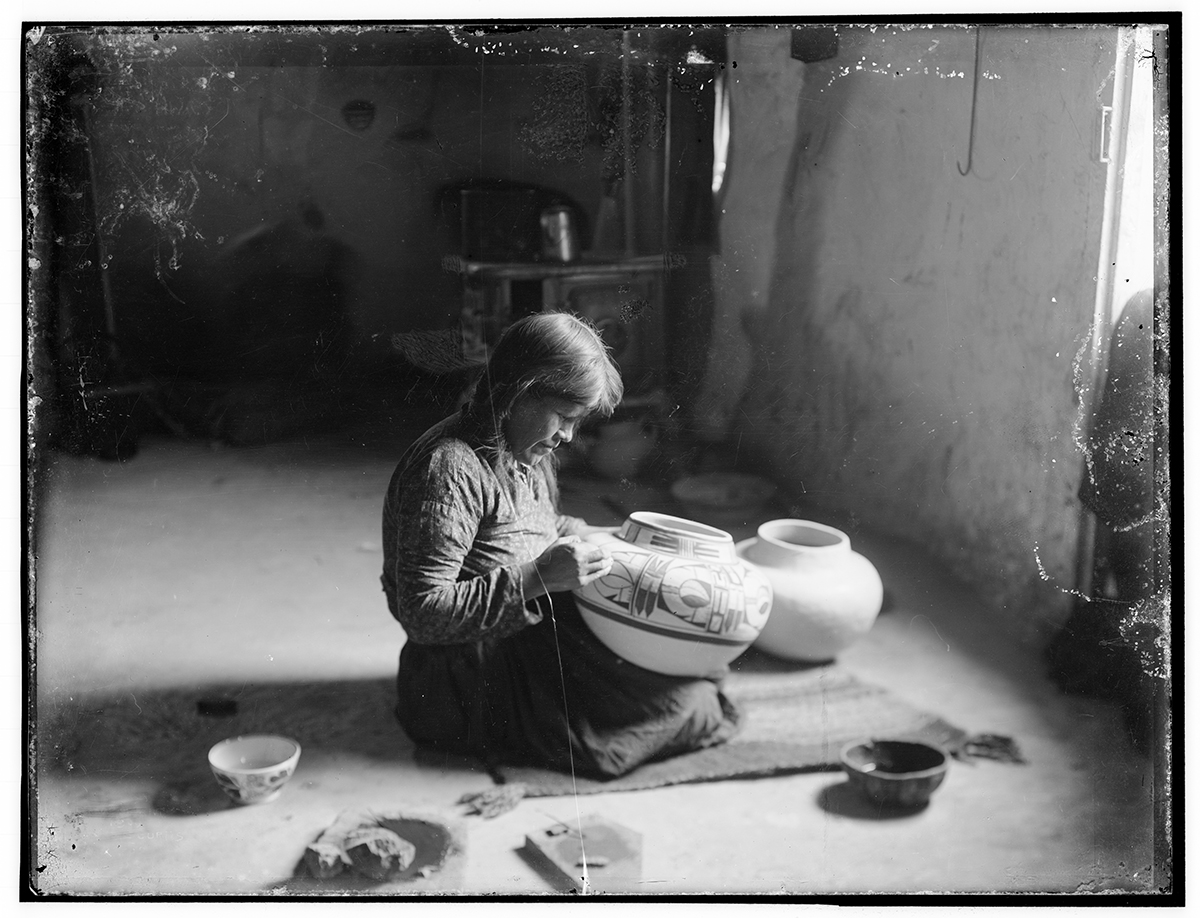

As Nampeyo’s fame grew, she increasingly interfaced with the larger world. She was photographed by Edward S. Curtis and other Western photographers, demonstrated her practice at the Fred Harvey Company’s Hopi House tourist attraction at the Grand Canyon, and traveled to Chicago to exhibit her work twice. Although a celebrity narrative of Nampeyo seems alluring, Dittemore points out that for much of her life, Nampeyo lived on an isolated mesa, immersed in Hopi-Tewa community, culture, and ceremony.

Dittemore sees a pragmatic aspect to Nampeyo’s practice—she produced prolifically to support her family—and also describes a philosophical angle that distinguishes Nampeyo from modernism’s deeply encoded narratives of singular genius, technological accelerationism, and societal fragmentation.

“In Nampeyo’s time, the endeavor of pottery making is a family affair: someone is out digging clay, someone is making the pots,” says Dittemore.

I get a little bit impatient when there’s talk of trying to put Nampeyo into a larger art historical canon with Western values and worldviews.

For most of her career, Nampeyo rarely signed her work, and later on, when her vision was failing, her daughters would paint and sign her work for her. Dittemore explains, “The idea of signing a work is foreign to traditional Pueblo values. There is an understanding that the ancestors planted the seeds of the tree that you’re basking under.”

When it comes to corresponding compositional innovations between Pueblo potters and the modernists, Dittemore worries about sacrificing core principles and vital subtleties of both movements by forcefully intertwining them. She brings up the concept of parallel invention, or simultaneous human advancements in disparate places, as a possible explanation for some of the aesthetic synchronicity between Nampeyo and the modernists.

In Santa Fe, Elmore is in the process of matching Nampeyo’s life to the modernist hero’s journey. He’s writing a new book and shooting a documentary film that will tell the story of Nampeyo as a craftsperson who became a modern artist. Hidden in an alcove of his gallery is a storyboard of Nampeyo’s life, which matches her career “phase by phase” to those of her European contemporaries.

Part of Elmore’s argument hinges on a difficult-to-prove shift in Nampeyo’s mindset as her career took off. “Pottery, it’s not like leaves from a tree—they are individually made,” posits Elmore about Nampeyo’s eventual understanding of her practice. In other words, perhaps she came to conceive of her vessels like a modern artist: not as functional or ceremonial objects tied to a craft tradition, but as discrete artworks that told a story, pushed her aesthetic forward, and sold on a global art market.

Elmore elaborates on this conclusion in his book: “In the end, Nampeyo was not an ancestral potter, nor even a traditional Pueblo potter, although these conditions were the context for her achievements. While she was trained as a traditional potter, she evolved into a unique artist using modern marketing techniques to sell her work to a new Euro-American audience.”4

Nampeyo in Hopiland

Nampeyo set the auction record for Southwestern Pueblo pottery at Bonhams in 2010 when one of her vessels sold for $350,000.5 She originally traded the piece for a sack of flour. Dan Namingha, Nampeyo’s great-great-grandson who was born eight years after her death in 1942, seems unruffled by this story.

“Yeah, she did a lot of trading for metal cups and dishes, utensils, sacks of flour,” he says. Namingha has a similarly unembellished response to the question of Nampeyo’s relation to the modernist pantheon, although a little smile plays at his lips. “These European and non-Native American artists were inspired by Indigenous cultures throughout the world,” he says. “It kind of goes full circle, you know?”

Namingha was born and raised in Polacca, a community at the foot of First Mesa that is named for Nampeyo’s brother. Namingha’s mother Dextra Quotskuyva Nampeyo was one of many master potters in Nampeyo’s ancestral line, but Namingha chose different modes of artistic expression. His paintings and prints appear with sculptures and photographs by his sons Michael and Arlo at Niman Fine Art, their family-run gallery in downtown Santa Fe.

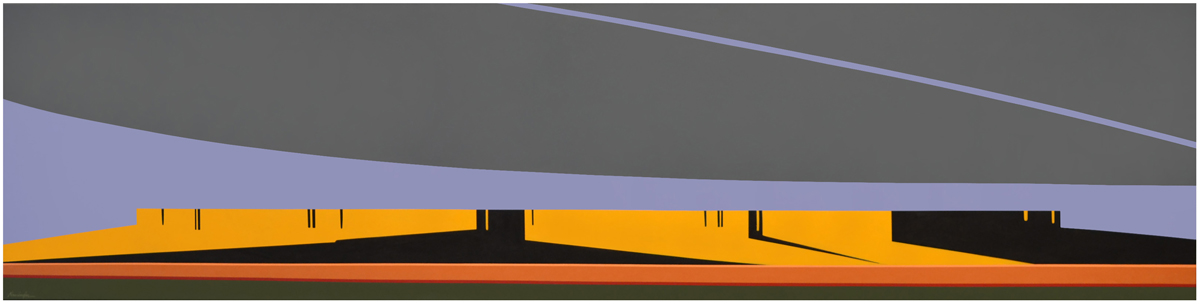

From a couch at the back of the space, Namingha waves towards one of his large acrylic canvases, bearing hard-edged geometric forms that depict light and shadows across the face of a mesa. “My grandparents raised me on their ranch, so I grew up studying the landscape on horseback,” he says. “That is a place between Flagstaff and the Hopi reservation, which is a ninety-mile stretch, and you see that one mesa the whole way.”

Although the abstracted building blocks of his painted vernacular seem to reference modernists like Josef Albers or Adolph Gottlieb—subjects of his studies at the American Academy of Art in Chicago—Namingha most directly ties his aesthetic to his ancestral land and culture. “You go centuries back, a thousand years back, and you see designs on pottery shards,” says Namingha. “They seem very abstract, but they have a meaning, a deep spiritual meaning.”

He points to a smaller painting, an abstract composition from his long-running Points Connecting series, that shows curvilinear forms linking at sharp points. “When we create these designs, we’re depicting our daily life. How we’re connected to the movements [of our natural surroundings], how we participate in ceremonies, how we hear the songs. All of this is inscribed by our own personal vision,” he says. “We indeed depict these things, but in a very abstract way.”

Namingha’s ancestrally grounded but experiential and ever-evolving vision aligns with the emerging philosophy of the Canadian scholars Ruth Phillips and Elizabeth Harney, who in 2011 launched an ongoing project called Multiple Modernities: Twentieth-Century Artistic Modernisms in Global Perspective.

Through academic curricula, writings, and a conference series, the project’s collaborators have mapped numerous centers of “co-modernist” art activity across the world. In their work, they try to avoid completely marooning lesser-known artists of the modernist period in traditionalist frameworks—or wholly contextualizing their innovations in relation to the European or American avant-gardes.

Phillips and Harney write in a project summary, “We are beginning to acknowledge the ways that these unexamined artistic productions challenge long-held values of authenticity and value, and to appreciate choices of materials and artistic methods that are often distinctive in relation to European models and present highly adept mixes of the local and the global.”6

Ultimately, Namingha’s most potent family legends of Nampeyo have more to do with things that unfolded outside of her pottery studio. “She had a lot of responsibility as the head of our clan, which is the (Tewa) Corn Clan,” he says. He describes Nampeyo’s duties of grinding and storing cornmeal to prepare for ceremonies, blessing and purifying snakes for the Tsu’tiki or Tsu’tiva (Hopi Snake Dances), and leading the clan house.

“What kept her humility was the fact that she had these responsibilities within the tribe and within the ceremonies,” Namingha says. “These are her duties, that’s what she did. And then on her time off, she would do her pottery.”

Nampeyo in the Mind’s Eye

A common misconception about recurring Pueblo pottery motifs is that they have sacrosanct meanings. Dittemore says non-Native curators and scholars often erroneously assume that there’s “a dictionary of definitions with their interpretations, that every single Hopi person who ever made this design on a pot had the same thing in mind. It’s an almost incurable lust for being able to interpret and find a code that could be applicable across all of it.”

Nampeyo’s most famous motif is known as the migration pattern, and its intersecting lines are said to trace the spiritual journey of the Hopi people through four manifestations of the world.7 The design’s slanting forms, enmeshed grids, and transitory themes could easily fold into quasi-spiritual modernist paradigms of exponential human progress. All abstract art is a Rorschach test, but Nampeyo’s historical context casts troubling shadows on either side of this interpretive coin for the non-Native beholder.

White-led cultural groups received ample acclaim for reinforcing the traditional aspects of Pueblo potters’ work in Nampeyo’s lifetime. In a 1998 essay for Journal of the Southwest, Margaret D. Jacobs describes the racist preservationism of early-20th-century white women from the New Mexico Association on Indian Affairs. Jacobs writes, “The women of NMAIA hoped to remedy [the] ‘tragedy’ of ‘mongrelized’ Indian art by educating both the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) and the public about ‘true’ Indian art, and by promoting those artists who remained true to their ‘racial talents.’”8

What kept her humility was the fact that she had these responsibilities within the tribe and within the ceremonies… And then on her time off, she would do her pottery.

Recognition for Nampeyo’s experimentalism has also passed between white hands, particularly regarding her impetus for reinterpreting designs on ancient pottery sherds. The archaeologist who completed a major dig at Sikyátki and Nampeyo’s longtime pottery trader have both received credit for stoking the Sikyátki Revival, even though Nampeyo drew inspiration from sherds and traded her own work long before either of them entered the picture.

The question of Nampeyo’s commercial success—and the distribution of the wealth that she and her family generated—is equally fraught. Representatives of the Fred Harvey Company called Nampeyo and her party “pretty independent and pretty much spoiled” during their stint at Harvey’s Grand Canyon tourist trap. An internal memo reads, “They did not want to do anything unless they were paid for it […] on the other hand, Nampeyo and her daughter are excellent pottery makers […] the Indian children are the greatest attraction of the Canyon.”9

Elmore doesn’t have much patience for queries about the weighty historical implications of reshaping Nampeyo’s legacy, especially as a white art dealer, or the potentially peripheralizing effects of defining her in relation to European artists who may have appropriated her aesthetic to garner much greater fame and fortune. He calls notions of cultural theft “childish,” arguing that “the only people that care about that are political animals—artists don’t care about that.”

Elmore’s vision of Nampeyo as a modern artist is a heroic one, zooming in on her as the driving force of the creative and economic phenomena that surrounded her—but it also crops out turn-of-the-century power structures. Born and raised in Carlsbad, New Mexico, and a practicing painter himself, Elmore seems to view Nampeyo as a Southwestern compatriot: independent, rebellious, and never quite getting her due from the art world establishment.

“That’s the reverse of how she’s seen—she’s seen as a product,” Elmore says. “I think it’s very clear that she was a strong individual who knew her work [and] knew she was worth more than that.”

Update 4/5/2024: This article has been updated to reflect that Harvard University’s copyright infringement lawsuit against Steve Elmore ended in a settlement.