The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

ITSFOMO September 14, 15, 16, 2018

History Keeps Me Awake at Night, July 15-September 30, 2018

A snake rides in the grass. A rat materializes in front of it. There’s not much doubt how this encounter is going to end. Yet, as the opening gambit of ITSOFOMO (In the Shadow of Forward Motion), artist David Wojnarowicz’s 1989 multimedia performance/electronic opera reprised at the Whitney on September 14, the imagery and sound deed no conventional narrative. Rather, the pacing spirals through relentlessly concentrated action, a visual-aural insistence on memory outlasting darkness.

In 1989, Wojnarowicz, recently diagnosed with AIDS, was animating in ITSOFOMO the dynamism that works spirit and body. Time is his performative subject, a time on the clock in which art and life and death sped up. What had he been doing with his time?

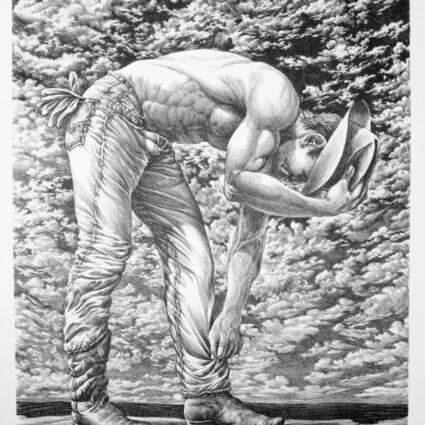

Wojnarowicz had been working with insistent energy to make art and record, in the forms of diary, essay, paintings, graphic art, film, video, and photography.

Immediately after his mentor and lover, the photographer Peter Hujar, died in 1987, he began An Archive of the Death of Peter Hujar. He filmed several minutes of Super 8 footage of Hujar’s body and took twenty-three still photographs of Hujar’s head, feet, and hands before he broke down, grief-stricken, in the hospital room.

As phenomenology of the memento mori, Wojnarowicz’s “archive” danced a kinesthetic duet with mortality energized by lamentation. He’d been continually writing, too, and published his “memoir of disintegration,” Close to the Knives, in 1992, a year before he died at age thirty-seven.

In the ensuing years, living witnesses decry the lack of any national public memorialization of the AIDS crisis or of its victims. (The AIDS “quilt,” considered the largest piece of community folk art in the world, was last displayed in its entirety in 1996.) Meanwhile, critical voices have put theory behind Wojnarowicz’s art of mourning that both borrowed from a Victorian postmortem photo genre and blew it up.

Emily Colucci, writing in American Suburb X, said the body of Wojnarowicz’s art does its political work by “revealing silences”—a poetic concept for the prodigious artist. As the retrospective History Keeps Me Awake at Night shows, the artist reveled in a spectral surround of decay while quickening his imaginative typology of disarticulation.

“I always feel uncomfortable when somebody says my work is political—I have a knee-jerk reaction to that,” Wojnarowicz told Steven Dubin in an interview on New Year’s Day, 1990.*

I recalled the sentiment’s spirit, if not the words, as I listened to an audience member wax windy before the performance began about the supposed ways Wojnarowicz’s paintings had pushed his “agenda.”

A track of his voice, strong yet ragged, roved through declamatory lines, “I have contracted a virus,” to ominous koans, “I have contracted a diseased society” and “Smell the flowers while you can.”

For those—including me—living through the 1980s in New York, “agendas” that implied/required being able to predict something or anything gave way to the tending of friends who were, in Wojnarowicz’s words, “waking up with the diseases of small birds or mammals.” A verse in ITSFOMO constellates his confession about moving to help a dying friend out of bed. The words “I was not strong enough” pinned me to my seat with a mimetic memory of precisely such a traumatic contest I had with a dying friend. He fell down.

Wojnarowicz would have turned sixty-four years old on September 14, the day of ITSOFOMO’s reprise after a twenty-five-year silence in New York. His composing partner, the mutantrumpeter Ben Neill, walked onto the Whitney floor with percussionist Don Yallech, the Psychedelic Furs drummer who also performed in the original trio. Empty music stands articulated Wojnarowicz’s absence. A track of his voice, strong yet ragged, roved through declamatory lines, “I have contracted a virus,” to ominous koans, “I have contracted a diseased society” and “Smell the flowers while you can.” Seedpod-shaped gongs reverberated. The mutantrumpet proliferated new horn-flowers. The intimacy of the artist’s voice conjured him into the room.

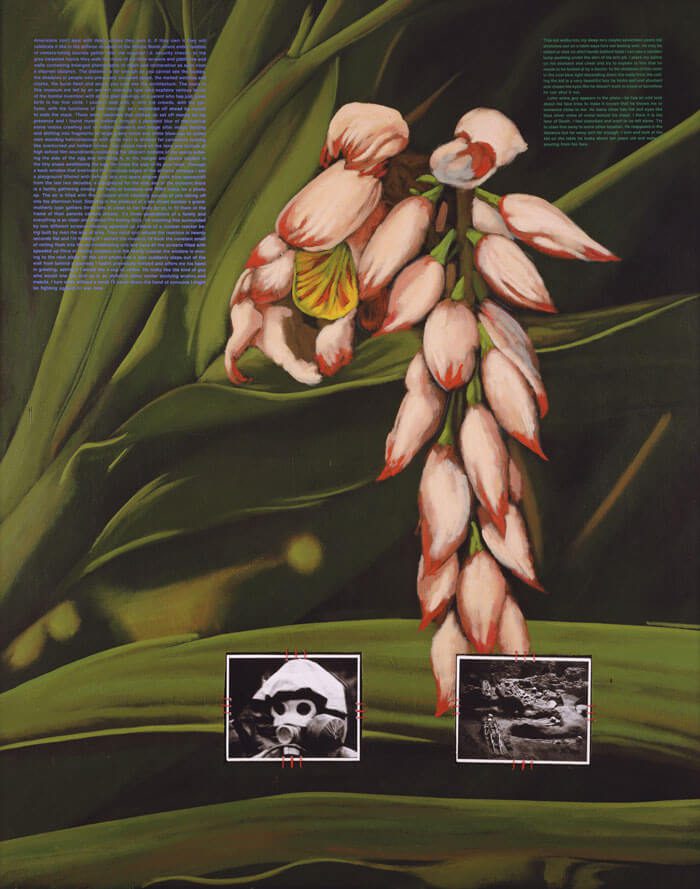

The imagery of ITSOFOMO is ordinary yet spellbinding, clear yet furred, racing yet pausing at tense thresholds between consciousness and the liminal. One goes underwater with the forms of beluga whales swimming; then into a broad, desiccated field where an ape lies on her back, fingering her hole; then into the blackness of a pier where two men dance, their silhouetted bodies white as shadow puppets. Eros, the flicking images attest, is life’s driving, proliferative impulse—our fundamental, elaborate syntax.

While the ugliness of the crisis proliferated—insurance brokers come calling to reverse-mortgage young people’s term-life policies; figures in politics, religion, and media smiling blandly while malignantly declining to act—Wojnarowicz argued for beauty. He told friends that he was working for his work eventually to be permitted to take its place in beauty, even if such a post-crisis future was then unimaginable.

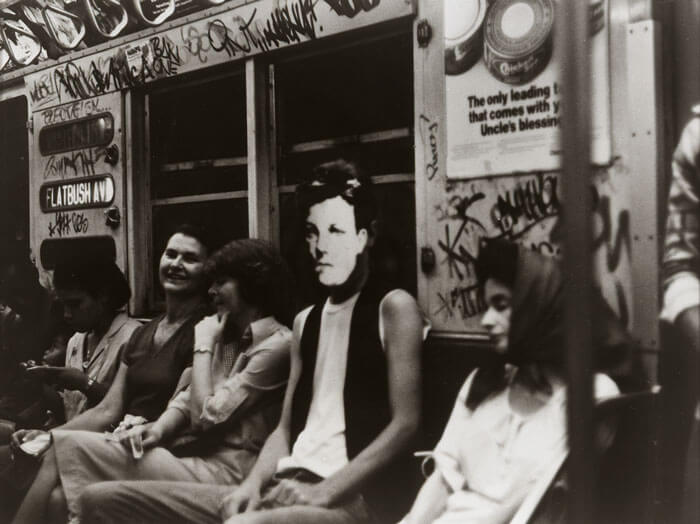

On the Whitney’s fifth floor, where I returned with a close friend to see the History exhibition a week after ITSOFOMO, we talked quietly about experiences we hadn’t talked over maybe since the time they occurred, even though we both lived there, same neighborhood, same clubs, same hospitals. Three acquaintances stepped off the elevator and moved onto the show floor, speaking of homage and active memory—a brief reminiscence of Civilian Warfare gallery; and of the now luxury condo that was St. Vincent’s Hospital, and the ruined catacombs where Wojnarowicz ported his Rimbaud mask and camera.

Made a sudden hero by the culture wars in the late 1980s, Wojnarowicz, and his essay for Nan Goldin’s curated exhibition, Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing, led the National Endowment for the Arts to pull the show’s funding. He’d written about Cardinal John O’Connor, the head of the New York Catholic Church: “This fat fucking cannibal from the house of walking swastikas should lose his church-exempt status and pay taxes retroactively for the last couple of centuries.” Approached to “revise” his statement, Wojnarowicz agreed to take out one word, “fucking.” “People will posture to the press on a certain level, and when really pressed to define themselves or to make a move or to act in a certain way to protect what they’re fighting for, publicly they’ll posture and bluff, and that will be it. And that’s what I experienced at Artists Space,” he told interviewer Durbin in 1990, referencing the show’s venue.

He filmed several minutes of Super 8 footage of Hujar’s body and took twenty-three still photographs of Hujar’s head, feet, and hands before he broke down, grief-stricken, in the hospital room.

By now, proposals of context about Wojnarowicz’s activism and art activity in queer history— “dismantling,” “revealing silences,” “making private grief public”—have been restated repeatedly. Yet contact with ITSOFOMO is far more a physical than an intellectual grappling with what he was up to: gesture, action, vitality, illegality, subversion, aesthetic activism, occupation, visual poetry. ITSOFOMO’s accelerations make a profound statement about living and dying by the relentless grip of time. Death, inevitably, subtracts. But not before a plangent reverb shrieks that eros multiplies, that eros loops desire and creation into a biological helix.

It makes a sickening, inevitable finale when the snake in the grass lifts its ghastly white head, then opens its maw and swallows its rodent prey. I sat, stunned, as people rose around me, wildly applauding. Time had compressed so intensely that I felt dislocated, hurtled into a feeling I jotted down as unremitting grief.

“Delight is as the flight— / [. . .] A Skein / Flung colored, after Rain,” poet Emily Dickinson wrote. Wojnarowicz’s energies made his place in beauty sure.