The artists and families tied to soon-to-be-demolished Salt Lake City murals depicting people slain by police diverge on how best to preserve their legacy.

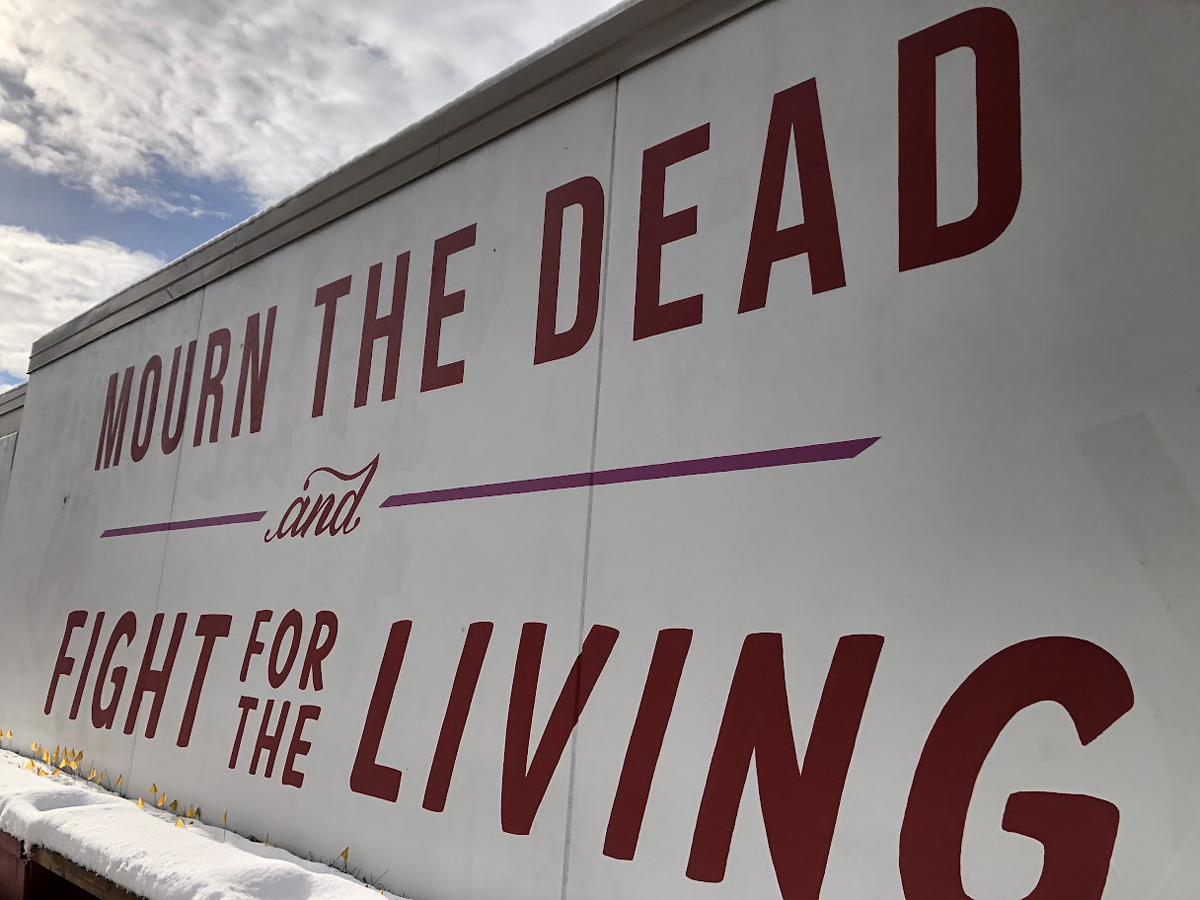

In the pivotal days and weeks after George Floyd’s May 2020 murder, artists mobilized to erect countless visual reminders of the marinating national trauma unfolding around them. In what would become the largest series of protests in United States history, the Black Lives Matter movement sought a reckoning with America’s systemic racism and the untold deaths of marginalized communities at the hands of law enforcement. What began as a simple but striking portrait of George Floyd’s face painted on one panel of an abandoned building in Salt Lake City’s Fleet Block District quickly spread to neighboring sections of the enormous structure, each bearing the image of an individual killed at the hands of police. The site soon became a stop on marches against police brutality and a place of remembrance for the individuals whose likenesses beckon recognition from those who traverse the well-trafficked street.

The project of multiplying portraits was the brainchild of SL Mural Makers, a collective of anonymous artists. For years those who consider the site a sacred place of remembrance have remained in limbo regarding the fate of the portraits. In recent weeks, Salt Lake City has unveiled development plans for the site that include a demolition of the building that bears the portraits.

The large, white structure located at 300 West and 900 South in Salt Lake City covers the entire block, wrapping around neighboring side streets. Each portrait is crafted in a similar aesthetic and palette, individual faces looming largely within the boundaries of sizable square panels. In addition to George Floyd, national figures like Breonna Taylor and local victims Bernardo Palacios-Carbajal and Bobby Ray Duckworth adorn the building’s edifice.

We are concerned about their faces being replicated at a site that perpetuates gentrification and harm in our city.

Recognizing the uncertainty of the site’s future, in April 2022, relatives of those depicted in the murals penned a letter to Salt Lake City mayor Erin Mendenhall. In it, they suggest a replica of the murals at the site of the former structure or elsewhere, referring to the site as a “police brutality healing space.” While proposing various options for commemorations in the redeveloped space, the letter cautions that, “we are concerned about their faces being replicated at a site that perpetuates gentrification and harm in our city. We see it as important that this site not profit or generate income for the City as a destination that uses our lost family members as a means for profit.”

Yet it wasn’t until October 2023 that the Salt Lake City Council approved plans for a new neighborhood rezone of the area. The site, which covers nearly nine acres of property, is known as the “Fleet Block” because of its former purpose as the city’s fleet maintenance facility for police cars and other official vehicles. This plan would divide the space into mixed-use development parcels in addition to a three-acre public space managed by the city’s Public Lands Department. The City will also allocate public art funding for a commissioned art project at the site that captures the legacy of the original murals.

On Thursday, August 15, 2024, a community meeting at the Sorenson Unity Center took place between city officials and select families of the mural’s subjects, part of an ongoing conversation between the victims’ families and city officials that began as early as 2021, according to the Mayor’s Office landing page devoted to the project.

“As Salt Lake City moves forward with redevelopment of Fleet Block, the public and the families will be invited to share their vision for the future of a new roughly 3-acre public open space, which will be the site of a community-informed public art installation. Beginning in early 2025, a city-wide public engagement process will invite the community to reflect on the legacy of these murals and how future public art on the site can embody their spirit and the social justice movement they represent,” the Salt Lake City Arts Council shared with me in a prepared statement.

While the spontaneous and rapid pace of the mural project mirrored the swell of activism underlying 2020’s Black Lives Matter protests, public sentimentality for the site’s subjects has seemingly ushered a desire for permanence that stirs emotional reaction to the site’s impending destruction.

The whole point of that thing in the beginning was that it was a cop station, it was abandoned, it was going to be torn down.

And as family members and activists have expressed a shared desire to preserve the spirit of the site in another form, one artist involved with the SL Mural Makers, who still wishes to remain anonymous, describes preservation as contrary to the project’s original intent.

“The whole point of that thing in the beginning was that it was a cop station, it was abandoned, it was going to be torn down,” the anonymous artist told me in a video call. “The whole point of it being put up is it was white artists who didn’t want to put their name on something because they didn’t want to speak for Black people, but they wanted to support so they did it anonymously but knowing from the start it was going to be demolished eventually.”

And of course the Fleet Block murals are not the only recent example of corporate expansion upending a local art site. Last year, I reported on efforts to preserve the works of Ralphael Plescia’s Christian School, a hallmark site of outsider art on Salt Lake City’s State Street that was forced to shutter after decades.

Now, as city officials grapple with next steps, the community is also pondering the immense value of public art projects that capture the indelible emotion underlying their creation, whether or not such projects were ever intended to remain in physical form.