Molly Zuckerman-Hartung discusses her work and process on the occasion of her survey exhibition Comic Relief at the Blaffer Art Museum at the University of Houston.

Artist, writer, and educator Molly Zuckerman-Hartung came to painting as an antidote to the performance-based punk scene she was part of in Olympia, Washington in the 1990s. In her survey exhibition Comic Relief, the comedy, tragedy, vulnerability, and confrontation found in performance are evident within her two-dimensional and three-dimensional works, a testament to her formative years.

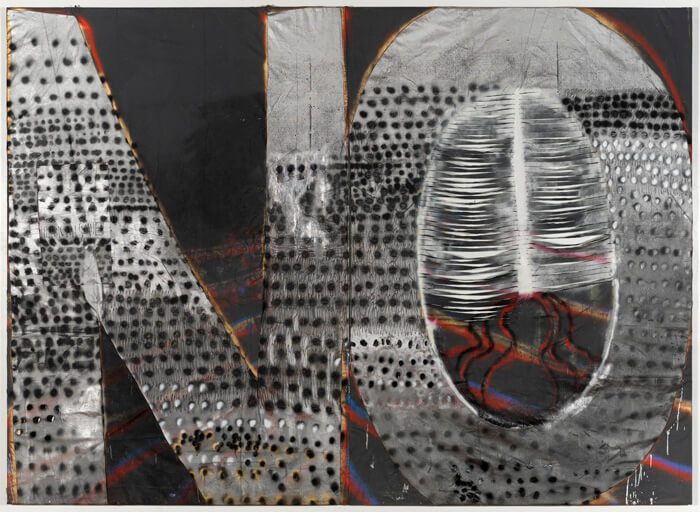

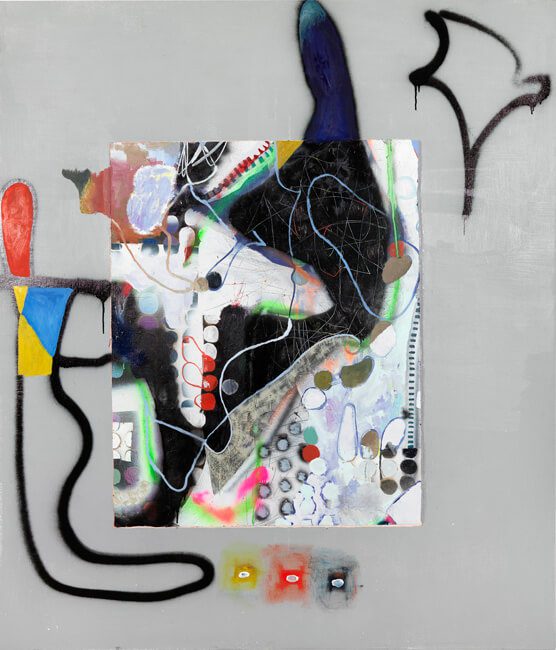

Comic Relief, on view at the Blaffer Art Museum at the University of Houston through March 13, 2022, contains over 100 works of art spanning twenty years, ranging from an early pinhole self-portrait to the large scale sewn and painted canvases she is known for today. In conversation with former student Annie Bielski (disclosure: Bielski contributed to the exhibition’s catalogue), the Norwalk, Connecticut-based Zuckerman-Hartung discusses her life, creative process, and what she’s wondered about for years.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Annie Bielski: Comic Relief is the title of your exhibition and a painting within it. The painting includes sculptural gloved appendages sewn into the canvas, with one draping to reach the floor of the gallery. I read them as tired performers giving one last spin before heading backstage, but getting caught in the stage curtain, the liminal in-between space. This piece also lives somewhere between two-dimensional and three-dimensional. In the context of this large survey of your work, I have been thinking about the solitary act of painting as the “backstage,” and the exhibition space and audience as its inverse.

Molly Zuckerman-Hartung: First of all, your reading is dead on. I liked that the surface of the painting can double as a theater curtain. That painting makes that so visible, and I’m thinking about how the back of the painting is backstage and the front of the painting is front stage, and that there is an onstage and an off stage. Once you understand that something is “performative,” or once you understand that there is an onstage, then you can begin to imagine an offstage. Offstage is always the space that I wanted out of painting.

The punk scene I grew up in in Olympia was all performance. It was very vampy, very draggy, and everybody was a musician, a singer, a poet. The performance aspect of the scene was so intense that I came to painting, not really understanding that I could work on something for a long time or that I didn’t have to show it immediately. I was constantly thinking of painting as a performance. I remember somebody at [the School of the Art Institute of Chicago] told me, “You know, you don’t have to show it to us until you want to? You can hide, you can work on it for years?” I remember being like, “Really? I can have secrets?” I just didn’t know what privacy was or what secrets were or what an inside was, but I wanted one really badly. So there was a kind of permission that was slowly being unearthed in painting for me.

Back to the term comic relief—it’s pretty straightforward on one level. It’s a joke, right? It’s a joke about the relief as a form, which is not painting or sculpture, it’s in-between, like the frieze. I like what you said about them being tired. It seems so obvious when you say it, they’re dragging, they don’t have a ton of energy left, but I don’t know if I’ve properly said that to myself.

I see duality in many of the paintings in the show. There are paintings hung perpendicular to the wall allowing the viewer to see both sides, there is a sculpture consisting of two chairs with their backs against each other, and there are the Queer Paintings made up of cut-out parts of one another that explore “difference within sameness.”

Let’s talk about our shared history. The discovery that I made in teaching [a “Stupidity” painting survey class that the author took with Zuckerman-Hartung] was about how humor doesn’t arise unless there are two. Somehow buddies or comrades or friends or partners or doubles were required in order to produce humor. Especially with somebody like [Samuel] Beckett, but with everything we read in that class—it’s not funny, it’s actually tragic. It’s very sad, very lonely. It’s like having a friend that makes something feel suddenly funny because they’re laughing at you, even though you are collapsing in some way.

The first idea for the Queer Paintings was from Judith Butler in Giving an Account of Oneself. I think she’s pulling from [Michel] Foucault and [Friedrich] Nietzsche in that book, and she builds this very intricate argument for the idea that we are hidden to ourselves because of our own unconscious and that in giving an account of oneself, or when I try to tell you who I am, I can only do that in a partial way. Also, it requires a you in order for there to be an account. I’m not getting the whole thing, but there’s this sense of how it’s not actually there’s a me and there’s a you, but there’s a narrative that comes out of the encounter. I think that had to do with the queerness. There are these ways in which sometimes you can become a real stranger to yourself in an encounter with somebody else, or there are ways in which we become strange. Trying to do this kind of physical transfer—I used to call it belly operations or surgery—was a way of trying to get at the way that we might encounter otherness in ourselves or difference inside of ourselves.

What I love most about your work is the sense that no material feels off-limits. When I was your student, you once said as an aside that if you have tuna cans around your studio they’ll show up in your paintings. I retained this as though it is a universal truth. How do you decide which materials and objects to bring into your studio? Do you seek them out with intention, or is it more intuitive?

I think historically it has been much less conscious, but what I’ve realized because I’ve moved so much, is that the studio is larger than just the room that I’m in. I think that a lot of what’s meaningful to me and important to me, or what’s getting caught in the semi-conscious, liminal consciousness, is the atmosphere. I think I’m an atmospheric painter by nature, more impressionistic than mass and volume-based. Some painters have really, really felt volume. Somebody like Cezanne really moved towards volumes, although of course, he was also incredible at atmosphere. Somebody like Monet—it’s all shimmer. The environments and places that I’ve lived in have had a massive effect on me as a kind of feeling. Growing up on the West Coast, living in the Midwest for so long, going to the South on my way to New York, and now living in New England—the studio these days is all New England. I’m a total packrat of New England objects because they crack me up. I’ve been digging up buckthorn trees and collecting their roots and hanging them and trying to think about roots and space and belonging, and also just looking at them. I keep finding broken caned chairs, so that keeps getting into the studio, partly because it’s a design that I can research, but often because it’s broken and it’s cheap.

This show contains over 100 works of art over a span of twenty years. Did you have any revelations about your work after mining your archive?

One answer is that [curator] Tyler [Blackwell] really wanted the show to be accessible. That museum is so much for the students at the University of Houston and they don’t use it as much as the people at the museum want them to. The accessibility and the pedagogical import of the show were impressed upon me from the beginning, and Tyler’s approach to that was trying to wed figuration to abstraction. He pulled in all of this old figurative work that I would not have put in and it turned out to be really interesting to me. I think the work became more pop, more iconic, and I thought about Mike Kelley in the show a lot. I don’t ever think that my work has anything to do with Mike Kelley, as much as I love his work and have been so inspired and influenced by it, but I think I felt that sort of comedy-abjection realm. The other thing that is maybe harder to describe or talk about, and is something I’ve wondered and thought about for years, is why is expression a problem for critical thought? In that show, I really started thinking, “I get it,” and now I feel like I’ve lost that. I don’t remember why I was feeling that, but I thought it was such an interesting sort of revelation. That would be the thing that I want to chew on.