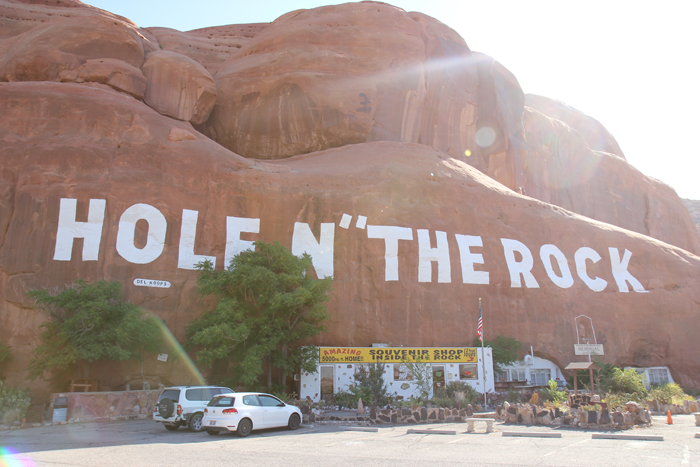

Hole N” The Rock—a 1930s excavated cave that honors Jesus Christ and Franklin Delano Roosevelt—is a feat of do-it-yourself architecture just off Highway 191 near Moab, Utah.

MOAB, UTAH—About thirty miles south of Utah’s favorite holey rock, Delicate Arch, there is a lesser-known rock hole that is, in some ways, even more quintessentially Utah than the state’s trademarked arches.

Hole N” The Rock (not a typo, just unusual punctuation) is a 5,000 square-foot man-made cave that was excavated in the 1930s by an ambitious and multi-talented couple, Albert and Gladys Christensen, to create a fourteen-room house, restaurant, bar, and dance hall.

This feat of do-it-yourself architecture is a perfect time capsule of mid-century Utah. It’s an ode to the audacity of mining outfitted in the style of country kitsch. The decor honors Jesus Christ and Franklin Delano Roosevelt with equal reverence.

Today, the eclectic cave dwelling is a roadside attraction off of Highway 191 just south of Moab. Ten-minute tours of the house run every day from 9 am to 5 pm and cost $6 for adults. The interior has been preserved exactly as the Christensens left it. A petting zoo—not part of the original vision—has also been added to the property, and I’ve met the local zebra supplier, but that is another story.

The entrance to Hole N” The Rock now opens up to a gift shop. “This used to be the bar and diner area,” says Bren Leigh, a tour guide who used to live on the property. An old photo tacked near the door to the kitchen shows a long bar carved from sandstone. “Let me show you something,” she says and crouches down. “We found old bottles and cans in there,” she says, pointing to a small, inconspicuous door that would have been behind the bar.

It’s unclear when exactly construction began at Hole N” The Rock. According to a pamphlet sold in the gift shop titled The Story of the Hole N’ The Rock [sic], an unofficial bar opened sometime in the 1920s during Prohibition. This checks out with the mysterious door behind the bar and Albert’s history as a bootlegger. Rum running eventually landed him in Leavenworth Penitentiary in Kansas, where he learned to cook, skills he would eventually use as the head chef at the Hole N” The Rock Diner.

Albert, who was working in the mines around Moab at the time, began construction on the main house in 1932 and continued for the next twenty years. The bar and diner were finished before the house, but excavation didn’t stop just because customers were enjoying their food, which, according to the pamphlet, consisted of burgers and steaks from poached cows and deer.

“They used to ring a bell before setting off the dynamite,” says Leigh. “If you heard the bell, you had to run outside.” The bar and dance hall were so raucous that a local judge eventually ordered the diner closed. “There were too many stabbings,” Leigh says. I asked how many stabbings were too many, but she didn’t know.

The tour of the house begins in the kitchen, which looks like a stereotypical 1950s suburban kitchen, except for the jagged rock ceiling, which was painted a pastel shade of uranium green to prevent sand from raining down on the food. The cabinets were custom-fitted to the unique contours of the rock, and a deep fryer was carved directly into the sandstone.

From there, the kitchen opens into the main house. There are no walls dividing the rooms, but there are three enormous pillars that partition the space and support the sixty-five feet of Entrada sandstone that weighs down from above. The pillars are wide enough to conceal a person and obstruct the views in ways that give the house an uneasy suspense.

The first “room” is Gladys’s bedroom where she slept after Albert died in 1957 from a heart attack at the age of fifty-three. Her collection of dolls strike various poses around the room. Minus the exposed rock ceiling, the bedroom itself has a dollhouse quality with its child-like matching furniture set and its plush pink rug.

If the dolls lend a sense of conventional hauntedness, the taxidermied animals provide a whole other level of bizarre and uncanny presence to the house. A man of many hobbies, Albert was also an amateur taxidermist, though not a hunter, judging by his selection of animals.

“These were wild horses that he found dead in the La Sal Mountains,” says Leigh. We were looking at a mustang immortalized not in a regal posture, as most stuffed animals are, but instead with its mouth in a rictus and its head and legs curled back unnaturally. “Rigor mortis had already set it, which explains their weird positions.”

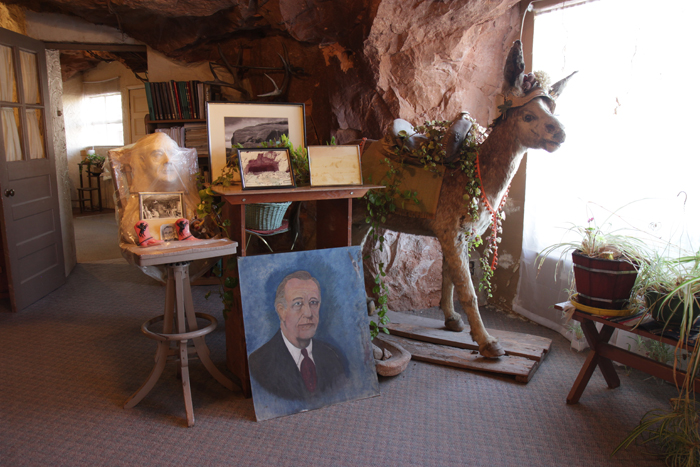

He also stuffed Harry, his loyal donkey who helped haul 50,000 cubic feet of sandstone out of the cave. “We call him Wonky Donkey,” says Leigh. Nothing about the stitch job is subtle.

In an archival photo printed in the pamphlet, Albert poses with another taxidermied donkey, which he positioned sitting on its hind legs like a dog and its floppy donkey ears standing upright like a jackrabbit.

“The ‘jackalope’ was a product of Albert’s taxidermy experiments,” the pamphlet states, referring to a creature of American folklore, a large jackrabbit with the horns of an antelope. “Albert had once toyed with the idea of turning the Rock into an Alice in Wonderland tourist attraction,” the pamphlet continues.

The home does have a whimsical charm and a fun house effect that distorts the proportions of one’s body, much like Wonderland. At the edges of the cave, where the ceiling slopes down to meet the floor, one feels very large. The unevenness of the ground makes you clumsy, like your feet are too big. The jagged ceiling forces you to duck in places you would not typically need to duck. And then, in the center, standing next to the enormous pillars or beside the rigor mortis horse, one feels small and rather delicate. At night, in the dark, I’m sure the deepest set grottos have an abyssal quality that feels not unlike a rabbit hole.

Even Leigh attests to the warping effect of the house. She says she climbed into the tub once—the house had running water and two functioning bathrooms—and the rim was up to her eyebrows. “And I’m six feet tall,” she adds.

During our tour, Leigh turned off the lights to demonstrate what it looked like before electricity was added to the property in the early 1960s. The diffused light from the softly curtained windows was surprisingly bright. This was the only way Albert ever saw the house—he died before electricity was installed. He only lived in the house for five years after it was finished.

Albert’s art studio was next to the windows. On his easel is a mock-up of the bust of FDR, which he eventually carved into the sandstone on the exterior of the house. “He was Albert’s favorite president,” Leigh says. “Albert was a bootlegger during Prohibition, and FDR ended that.” Albert’s other favorite guy was apparently Jesus, of whom he painted three identical portraits and one life-sized depiction of the Sermon on the Mount.

While Albert was in charge of the larger-picture rockwork, Gladys was in charge of the more refined stonework, such as the fireplace and hearth. “They didn’t really need it though,” Leigh says. “The house stays about sixty-five to seventy-two degrees year-round.” Albert drilled a sixty-five-foot chimney through the rock for the fireplace. “Lined it up on the first try,” Leigh says.

Gladys was also in charge of carving their gravestones. The couple is buried in a small cave a little ways behind the house, next to their cat cemetery.