Drawing on public and private archives and fifty years of personal documentation, Anne Elise Urrutia’s book Miraflores brings to life her great-grandfather’s San Antonio garden in unmatched detail.

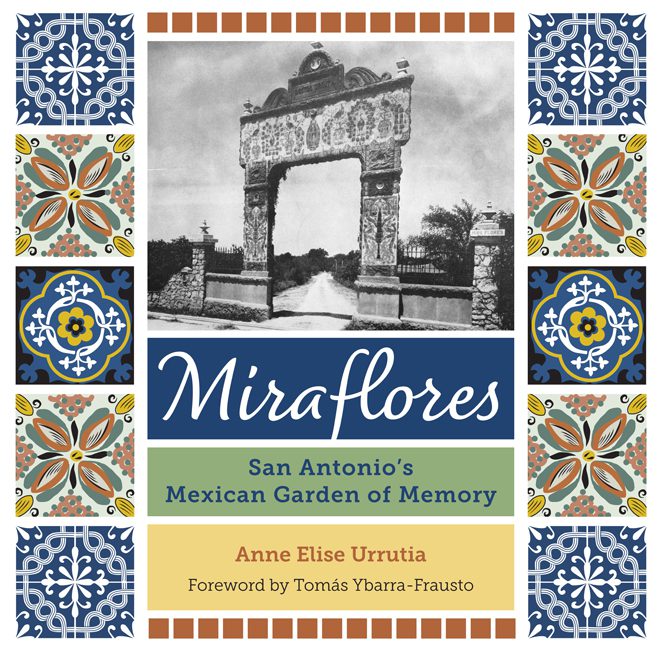

Miraflores: San Antonio’s Mexican Garden of Memory

by Anne Elise Urrutia

Trinity University Press, 2022

Last fall, I had the distinct honor of experiencing the Northern Virginia gardens designed by the late Rachel Lambert “Bunny” Mellon as an artist in residence at Oak Spring Garden Foundation, the organization created to preserve the famed landscape architect and horticulturalist’s gardens and expansive private library. Mrs. Mellon, whose botanical artistry can be seen in several of the White House gardens as a result of her close friendship with Jacqueline Kennedy, rightfully looms large in the canon of great American garden designers. Much has been written about her work, and though the estate was burdened with deep debts towards the end of Mrs. Mellon’s life, Oak Spring—particularly the central greenhouse and garden that served as her primary studio and canvas—remains exactly as she specified in life.

Such are the privileges of whiteness.

More than 1,500 miles southwest along the San Antonio River, the scene at Miraflores, the inspired creation of internationally renowned surgeon, community doctor, philanthropist, and patron of the arts Dr. Aureliano Urrutia, is much different. Though the garden and its collection of Mexican sculpture and decorative art represents quite possibly one of the most significant cultural artifacts in the United States, Miraflores has been neglected since the 1970s. Despite Dr. Urrutia’s condition in the deed selling the fifteen-acre parcel of land on which the four-and-a-half-acre garden sits of “keeping the place like a spot of beauty, without touching any tree, anything that corresponds to this beauty,” it is now in a state of ruin, and Dr. Urrutia’s preeminence as a botanical artist and collector and commissioner of exquisite Mexican fine and folk art has been unsung. It might have remained that way without the efforts of his great-granddaughter Anne Elise Urrutia, beginning in 1978 with her high school photographs of the garden and culminating nearly half a century later in Miraflores: San Antonio’s Mexican Garden of Memory, out in June 2022 from Trinity University Press. Like her great-grandfather’s feat before her, Anne Elise Urrutia’s Miraflores is a multi-layered masterpiece. It successfully combines rigorous biography, meticulously detailed art historical documentation/reconstruction, and extensive cultural history as context, all with a spell-binding lyricism, coming together to create the definitive text on the garden and the man behind it.

Anne Elise begins by correcting the existing understanding of Dr. Urrutia, which focuses on his life and legacy in San Antonio and flattens his identity as simply “Mexican American.” Miraflores paints a more complete picture. Starting with Urrutia’s childhood in the Indigenous village of Xochimilco, Anne Elise emphasizes the significance of his Indigenous heritage and benefit from pro-Indigenous educational initiatives, and chronicles his distinguished service as a battlefield medic and achievements as a surgeon, teacher, and landscape artist prior to his exile during the Mexican Revolution, stressing that “Miraflores was not Urrutia’s first garden, and San Antonio was not his first successful medical practice.”

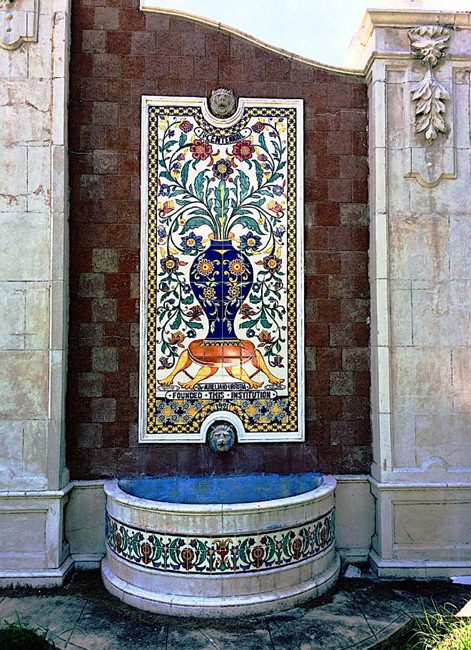

Over the course of the book, organized as a walk through the garden as it was in its heyday, Anne Elise Urrutia documents and explicates the garden’s objets d’art with the precision of a specialist, despite having no formal training in art history, archaeology, or cultural studies. Writing about the Urrutia Arch, one of Miraflores’s two main entryways, Anne Elise describes the imagery in lyrical detail: “Flora and fauna abound as six peacocks roost in blossoming cherry trees […] On each column a juniper tree—a tall variety of cypress native to Xochimilco—hosts more peacocks, surrounded on each side by rampant jaguars,” elaborates on culturally specific symbolism: “[…] The jaguar, on the other hand, in Aztec tradition, carries a distinctive message of protection and warriorship not universally common, thus easily misunderstood,” and notes the provenance and significance of the material on which all this rests: “The fanciful signatures on the tile indicate that it originates from the Uriarte tile workshop of Puebla, Mexico. […] here may stand some of the earliest Talavera tile used decoratively for a vertical exterior surface in the United States.” These intricate tapestries of description often rival the explanatory materials available in art and history museums, and the overall experience is like being given a private tour of an exhibition by the curator herself.

Beyond its singular contribution to botanical art history, Mexican American studies, and more, Miraflores is a stunning work of collaborative research-based art. Anne Elise’s spectral amateur photographs from her teenage documentation of the garden, her lush, evocative prose, and the beautifully hand-drawn and watercolored maps contributed by San Antonio architect Rebecca Schenker make the garden spring to life. Of the non-extant Rose Courtyard, she writes, “In this secluded and shaded chamber, deep in the garden center, a peace awaits. […] Castilian roses perfume the air as they climb along the esplanade walls. Water trickles from lion’s head spigots, performing a quiet lullaby.” On the next page, a photograph of the scene completes the sensory immersion, and though I’m in my second-story duplex just north of downtown Houston as I read, I’m completely transported.

Dr. Urrutia had a fondness for connecting people and events through time—the Monumento a la Ciudad de México, one of the garden’s two elaborate entrances, “commemorates the ‘IV Centennial’ […] Hernán Cortés founded Mexico City in 1521 and… four centuries later, in 1921, Urrutia founded this institution (Miraflores),” writes Anne Elise. Her own Miraflores coming out in 2022 marks another century, and as the elder Urrutia’s Miraflores was dedicated to the Mexico City lost to him through exile, so the younger Urrutia’s Miraflores is dedicated to the garden of her ancestor and all the splendors it has lost to the United States’ systematic failure to protect the cultural contributions of people of color. Though that neglect is slowly being corrected—the city of San Antonio’s acquisition of the garden in 2006 and its subsequent addition to the National Register of Historic Places has made gradual restoration possible—it remains to be seen whether Miraflores will ever return to its original glory. Miraflores, then, is both elegy and prayer. “I hope this book will help Miraflores find new life,” Anne Elise writes in the epilogue. “With proper care and support, Miraflores could again offer the community a unique place where Mexican history and culture can be discovered, explored, understood, and celebrated.”

I, too, would like to see that day, and experience the garden as I did Oak Spring—fully reflective of the genius of a great bicultural artist.