June 22 – August 31, 2019

516 Arts, Albuquerque

“The ideas of work and comfort are mutually exclusive to me,” I told my friend Maggie as we walked into Mira Burack’s show, Sleeping between the Sun and the Moon, in the upstairs gallery at 516 Arts. Maggie was talking about her habit of working from bed, a practice that, she mentioned, writers such as James Joyce, Marcel Proust, and Colette also partook in, but one that I couldn’t conceive of trying myself. I imagine I would just fall asleep.

It’s clear that Mira Burack has no such hang-ups about the intermingling of these two seemingly competing ways of being. The images that abound in her work are those of rest, comfort, and domesticity, the last being an all too often narrow artistic theme that she expands elegantly. Her landscapes are interiors, those of the home, the bed, and the family, but they extend outward to include nature and wildness.

This cat’s cradle that Burack weaves between the cosmic, the natural environment, and the intimately domestic made intuitive sense to me once I saw several of her pieces together. Her Asteroid, a sphere of dried snakeweed hanging from the ceiling, reminds me of the lantern in the shape of a star that hangs in my partner’s daughter’s room. Many of the earliest stories we tell our children, perhaps the earliest stories of human culture, revolve around the stars: the story of Orion the hunter, of lost travelers guiding themselves home by the stars. I think of Burack putting her two children to bed at their home in the Ortiz Mountains, where the stars are doubtless much brighter than in comparatively urban Albuquerque. Reading Alicia Inez Guzmán’s essay accompanying the exhibition on visiting with Burack in her home, I learn that Asteroid originally hung in her daughter’s room. It seems like a parenting instinct, to tuck your children in at night and tell them: even the vast and unknowable stars are watching over you. Or, as Burack’s work suggests, even the coyotes and the snakeweed and the hot desert air are your home. What a comforting world to fall asleep in.

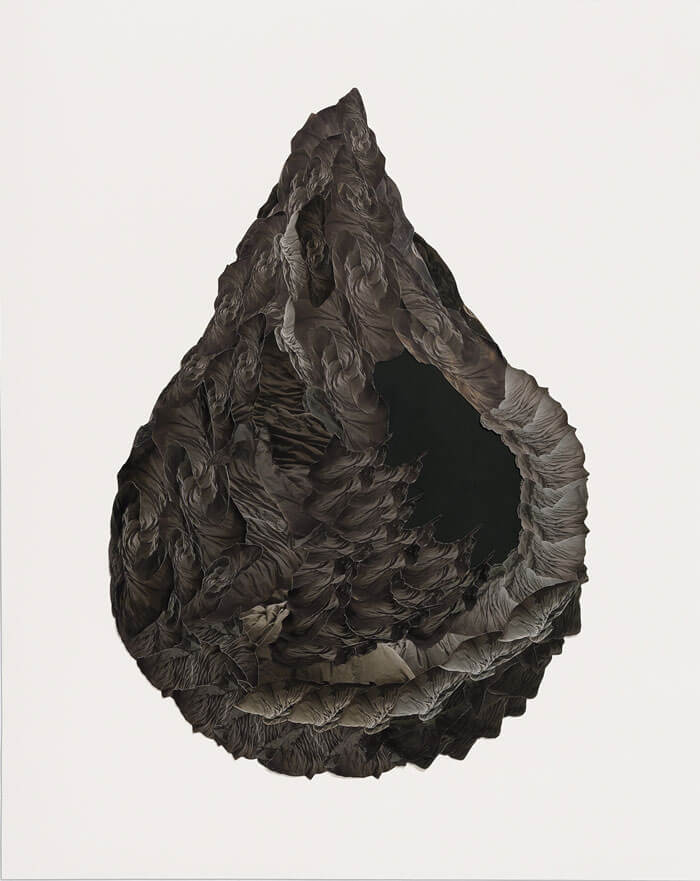

The pair of photo collages, (dark) Waterdrop and Waterdrop II, evoke sleep more than any other pieces in the show. Waterdrop II is composed of dozens of photographs of white bedding: sheets and lofty down comforters, the very image of lazy Sunday mornings spent in bed, sunlight streaming through the window, the kettle whistling in the kitchen.

The (dark) Waterdrop is made up of charcoal-colored sheets, looking murky, oil-slicked, and spiraling into a cavity. This darkness shaded into further darkness makes me think of the moment of slipping into sleep or, less innocuously, of surrendering into the all-consuming darkness of anesthesia, of the fears that accompany sleep: sleep paralysis, nightmares, jolting awake in the middle of the night with the inexplicable feeling that something terrible has happened to somebody you love.

Pieces like (domesticated) Bird House peer further into the dark side of sleep and certainly strike a different note than the bright and warm arrangements of blankets and dried flowers throughout the rest of the show. This black box, hovering a few inches off the ground on a pillar and humming with strange, theremin-like noises from within, is a thing brought back from the realm of dreams. Goose, chicken, and turkey feathers line the roof of the box, giving the surface a veneer of animality and life. There’s something foreboding about this mysterious device: what is inside? you wonder, unsure if you really want to know.

Even in the heart of all the warmth and familial care that hovers around her work, Burack acknowledges that there is darkness in each of us, even in our most tender or comfortable moments. We keep the lid shut tight on that little black box at our core that’s filled with the thoughts we don’t allow ourselves to think and the urges we don’t allow ourselves to act on—but nevertheless, its gravity affects everything around it.