In this psychogeographic account, Emma S. Ahmad wanders the West End Historic District in downtown Dallas and considers how the various memorials reflect the shifting political landscape of the city.

This article is part of our Living Histories series, a continuation of the ideas explored in Southwest Contemporary Vol. 9.

At 9am on a Friday morning, I stand in Dealey Plaza, a city park in downtown Dallas also known as the “birthplace of Dallas.” The first home in Dallas was built here, as was the courthouse and the post office amongst other businesses. I set out this morning to explore a few of Dallas’s memorials, both old and new, and this seemed like a good place to start.

In 1963, the area would go down in history as the infamous location where our 35th U.S. president John F. Kennedy was assassinated. I look down at the sloping hill, known today as the “grassy knoll,” which is already teeming with conspiracy theorists with their homemade pamphlets and DVDs in hand, ready for the daily wave of tourists to float through. The street is marked with white X’s, pinpointing the exact spots where Kennedy was fatally shot in his limousine. The grassy knoll slants down into what is locally known as the “Triple Underpass,” an area where three streets – Main, Elm, and Commerce – intersect to pass under a railroad bridge.

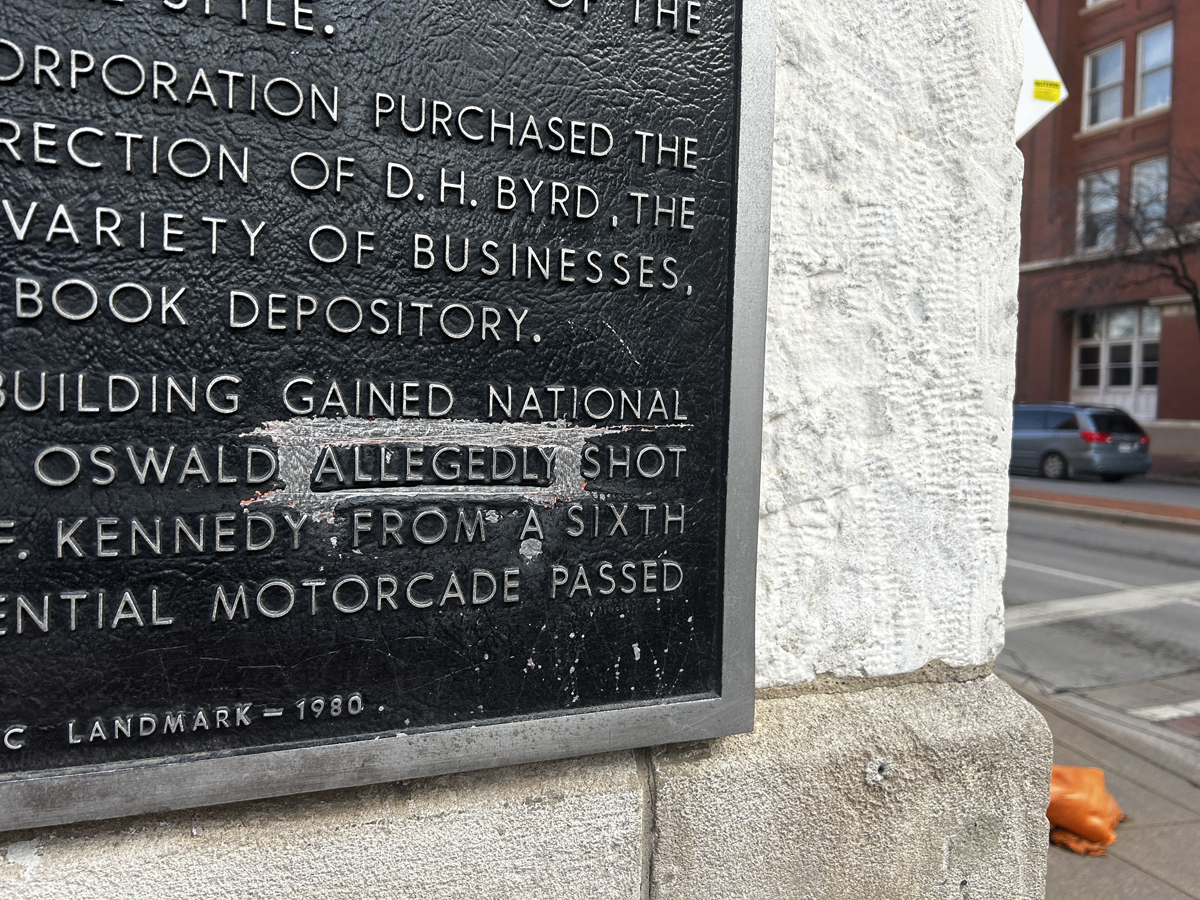

To my right sits the Dallas County Administration Building (formerly the Texas School Book Depository). The sixth floor of that building is the location where Lee Harvey Oswald fired the notorious shot that killed JFK and today that floor is a small museum. Opened in 1989 – decades after the assassination occurred – the Sixth Floor Museum explores the life and legacy of JFK and Oswald. At a lovely $25 ticket fee for adults (which was only $18 last year), I will leave a review of that museum to another.

But, alas, I did not come to Dealey Plaza to witness the grassy knoll with my own two eyes, although it is listed as one of the city’s “must-see” attractions on every other tourism website.

What I came to see was a more recent memorial residing on a neglected half-acre of land, supposedly nearby.

“I read online that there’s another city park around here,” I tell my friends and fellow historians, Jarod Rosson and Isabel Lee-Rosson, who joined me that morning along with their six-month-old. After staring at Google maps on our phones for a hot second, we all came to the same conclusion: to get there, we had to enter the concerningly ominous and uninviting pedestrian tunnel that leads under the Triple Underpass. In every sense, it feels like a trap.

But as we emerge on the other side of the tunnel, we are indeed greeted by a sad, triangular plot of land. Barricaded on all sides by busy highways and railroad tracks is an official city park called Martyrs Park; previously known as Dealey Annex, the site was renamed in 1991 to commemorate the lynchings of three enslaved Black men, Patrick Jennings, Samuel Smith, and “Old Cato” Miller, that occurred during the Texas slave insurrection panic of 1860.

The unkempt plot of land looks abandoned if not for the park’s sign (which simply states the name of the park, no explanation of the aforementioned events) and a large bronze sundial memorial. Created by artists Shane Allbritton and Norman Lee, the $100,000 memorial dedicated to the victims of racial violence, titled Shadow Lines, was finished just last year, in 2023.

Allbritton and Lee are co-founders of RE:site, a studio that “creates public art, memorials, and commemorative spaces that connect past and present by inviting the public to share in experiential moments, prompting collaborative viewership, curiosity, discovery, and dialogue.” Their steel sundial memorial includes a semicircular wall which is inscribed with the names of people killed through racial violence in Dallas County between 1853 and 1920. As the day progresses, the shadow created by the sundial design moves between the names of those victims. On one end of the wall is a statement by poet Tim Seibles dedicating the memorial to the victims of white supremacist violence and recounting the tragic deaths of Jennings, Smith, and “Old Cato.”

With not even a bench to sit on and noises from the dangerous highway coming in from only a few feet away, Martyrs Park is a disheartening attempt by the city to confront its history of racial violence. From the grassy knoll, you cannot catch even the slightest glimpse of the park through the entanglement of highway overpasses; it is wholly unwelcoming and inaccessible. I think about a quote from architecture critic Mark Lamster, who simply refers to the area (Dealey Plaza, the Triple Underpass, and Martyrs Park) as “the city’s most profound urban failings.”

Although the Shadow Lines memorial was a tangible success to many, even if it was a long time coming, its fruition can primarily be attributed to the relentless efforts made by prominent members of the community, such as Remembering Black Dallas’s founder George Keaton Jr.

Keaton also fought for a historical marker from the Equal Justice Initiative to denote the lynching of fifty-nine-year-old Allen Brooks, which took place in 1910. I walk just a few blocks away from Dealey Plaza and Martyrs Park, where, a little over a century ago, Brooks was forcefully kidnapped from the courthouse where he awaited trial for a crime, and murdered. A photograph of the horrific event was turned into a souvenir postcard.

As I stood in front of the Dallas County Courthouse, also known as the Old Red Courthouse, and thought about Allen Brooks, I found my attention veering left to the giant concrete box next to the courthouse: the John Fitzgerald Kennedy Memorial. The design of the structure is that of a cenotaph or an “empty tomb.” Raised a few feet off the ground, the roofless box is minimal and rather uninspiring. A statement on the placard by the architect, Philip Johnson, claims that it is “a place of quiet refuge, an enclosed place of thought and contemplation separated from the city around, but near the sky and earth.”

Historically, Dallas civic leaders were divided on whether or not Dallas would be the appropriate place for such a memorial. After hundreds of designs were proposed, in 1969, construction for the monument began and in 1970 an official dedication ceremony was held, attended by a few hundred people. It is attributed by many as the most significant memorial in Dallas.

Public monuments have been the hot topic of the last few decades, countless of which have been torn down and erected. Regardless of your stance, it is evident that there is power in what we choose to memorialize.

That morning I only walked a few blocks around the West End Historic District; what I saw was far from any sort of comprehensive narrative about Dallas. But I couldn’t help but think: how do these memorials shape how we remember the past – how we remember Dallas?

The JFK memorial and the Martyrs Park memorial do not exist in isolation to one another, just as the crimes that took place are not unrelated. Civil rights became a pivotal issue in Kennedy’s 1960 presidential campaign and following his election; part of the vitriol Kennedy experienced during this time was racially motivated. Dallas capitalizes off the JFK monument through the tourism that it brings to the city, yet it has taken over 160 years to fund and construct a memorial recognizing the heavily documented, savage murders of three enslaved men. It comes as no surprise that memorializing those lynchings, alongside others like Allen Brooks, is not the city’s priority, as that would lead to further acknowledgment of its history of racial violence. Which would, in time, lead to the increased demand for reparations.

“Monuments don’t mean things on their own,” claims Yale professor Jennifer Allen, who specializes in memory politics. “They mean things because we make them mean things.” Although public monuments and memorials like these appear permanent, their meaning is always shifting.

In an attempt to analyze the city’s changing political landscape, I stop and consider these memorials in interaction or in conversation with one another. If both are attempts by the city to rectify a history of violence while collectively honoring the memory of those victims, how does that speak to how the legacy of Dallas is evolving?