Cowboy cosplay, broken Spanish, and Indigenous erasure haunt Sagebrush and Solitude, the reluctant American modernist’s Western retrospective at the Nevada Museum of Art.

Sagebrush and Solitude: Maynard Dixon in Nevada

March 2-July 28, 2024

Nevada Museum of Art, Reno

“Long ago, I had to make a choice between being modern and being honest. After some experiments and self-searching, I chose the less gaudy of the two,” reads the archway above the entrance to Sagebrush and Solitude: Maynard Dixon in Nevada.

The exhibition, on view at the Nevada Museum of Art, is the first comprehensive look at the painter’s depictions of the state of Nevada, the Eastern Sierra, and Lake Tahoe completed between 1901 and 1944. An accompanying book of the same title showcases photographs of these pieces alongside poetry by Dixon and scholarship examining his life and work.

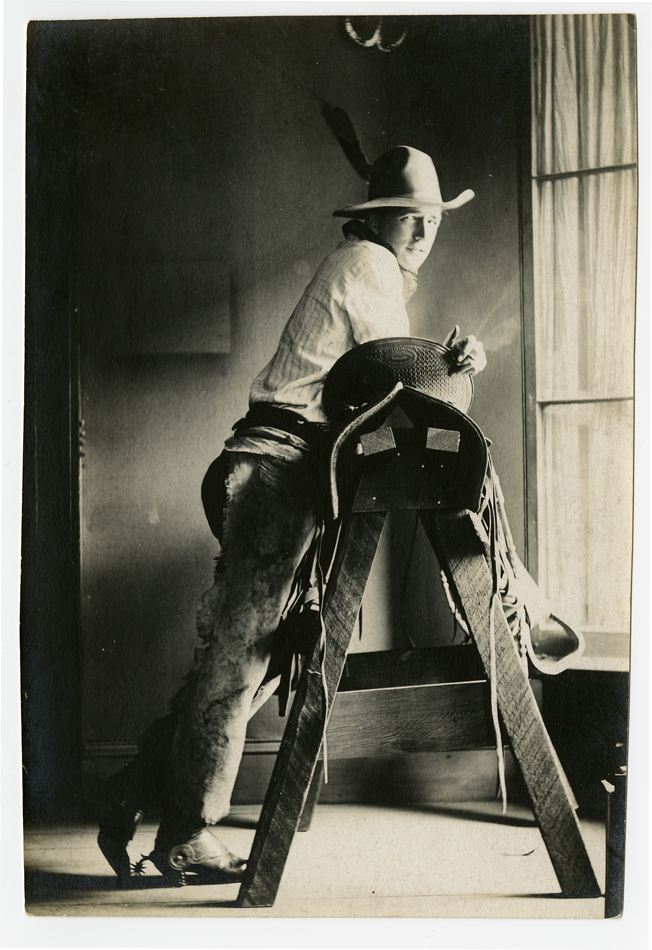

Attributed to Dixon, the show’s introductory quote stretches over a larger-than-life-size image of the largely San Francisco-based artist wearing full cowboy costumery and a Paul Newman smolder. His declaration is an interesting one, and an apt choice for display at the exhibition’s entrance, as it doesn’t quite make clear which of the two we should consider less “gaudy.”

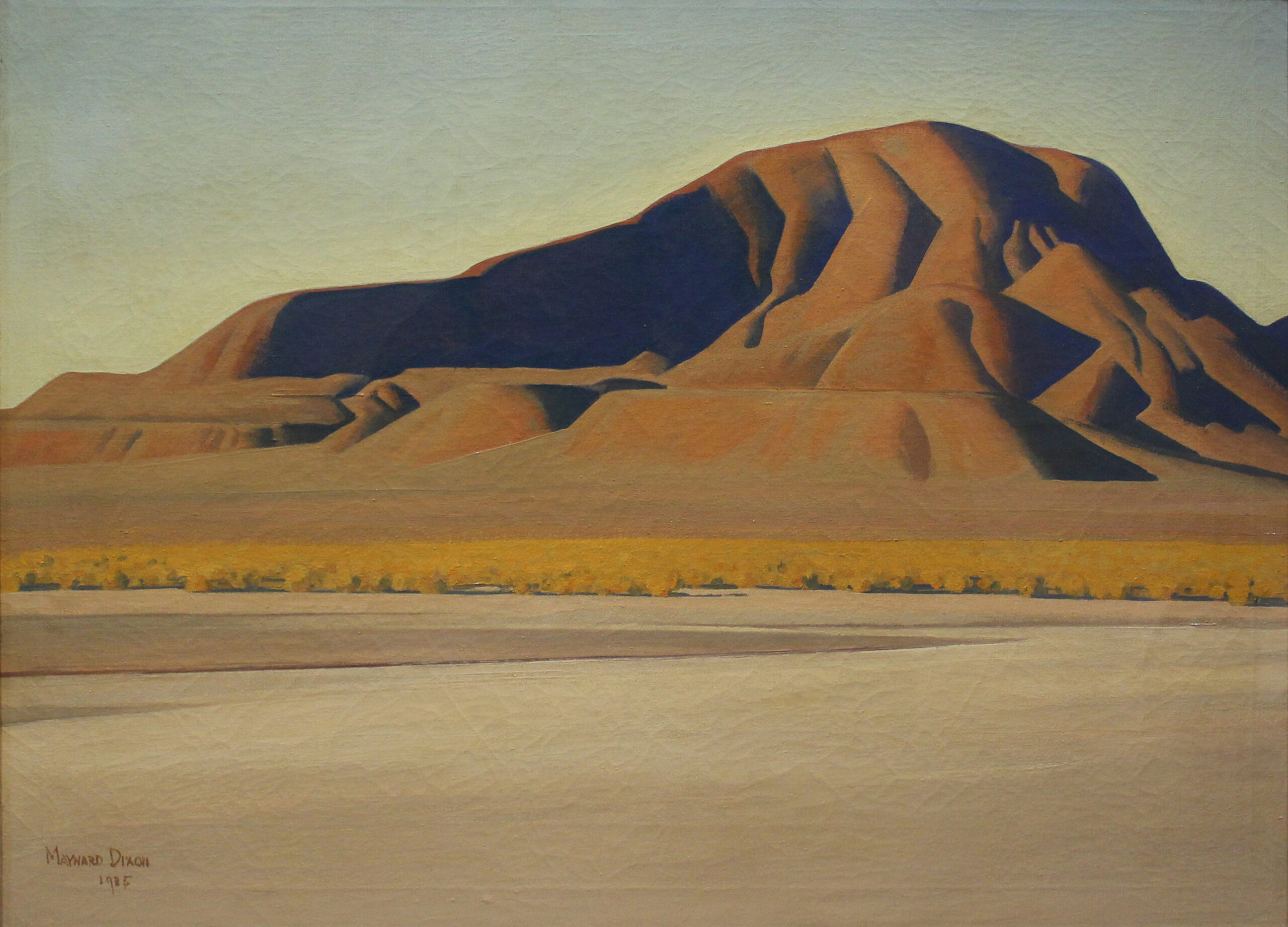

In making use of select modernist tenets—simplified compositions, limited color palettes, and a Cubist’s elucidation of underlying geometric structure—it would seem Dixon worked to approach something progressively less ornamented, even more honest. Yet, despite crediting Dixon with bringing modernism to Nevada, the exhibition’s accompanying scholarship documents Dixon’s feelings towards the movement as ambivalent at best and contemptuous at worst. Pitted against honesty, “modern” seems to be used as a pejorative in this context.

So then, maybe Dixon intended us to consider honesty as the less gaudy of the two. In the book’s introduction, curator Ann M. Wolfe recognizes that one of Dixon’s stated aims was to exhibit “ideals of truthfulness” in his work. Viewed in the context of his complete Nevadan works, just how honest is his multifaceted portrait of this landscape?

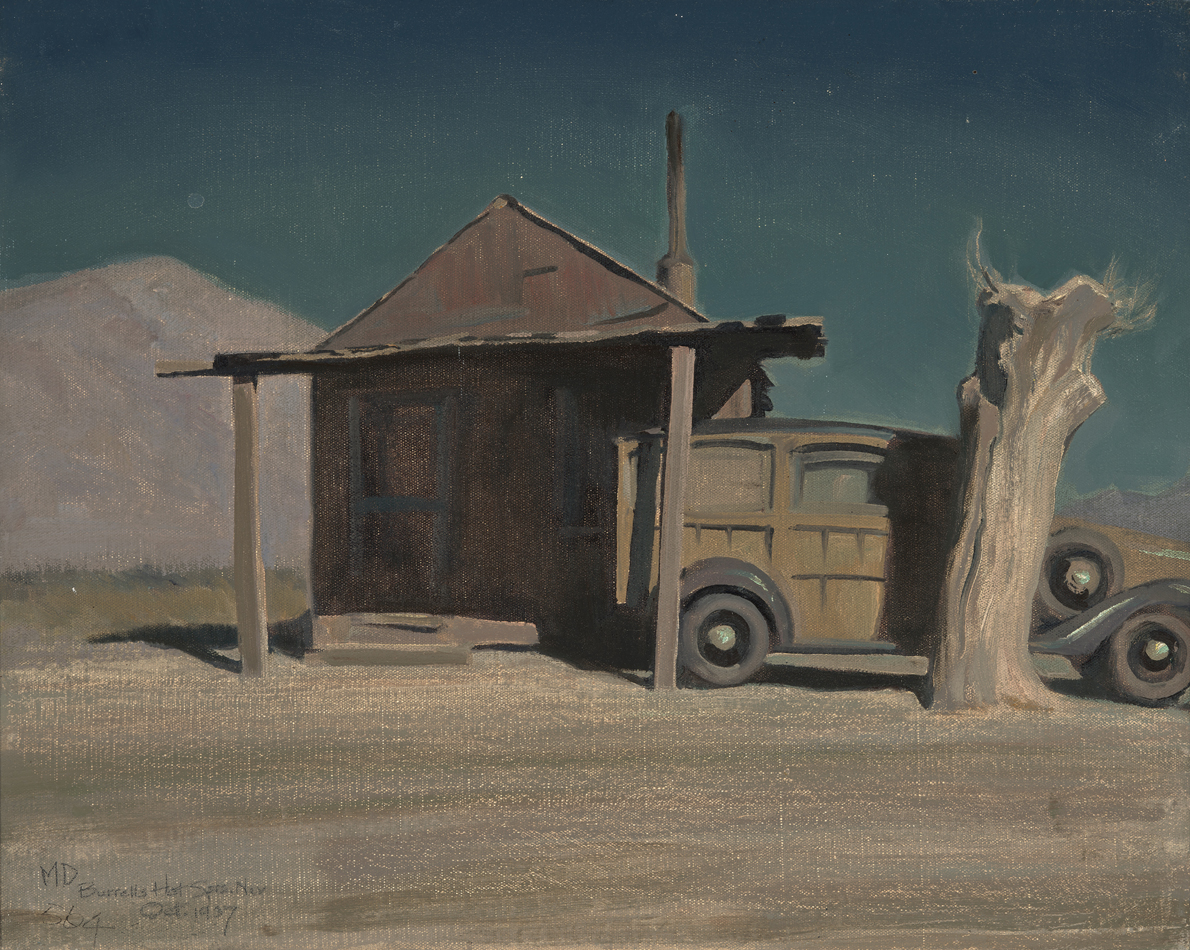

If you have lived in these regions, it is striking to view these landscape paintings that were completed a century ago—to time travel a little as you stand before the same low mountain you catch from the freeway rendered in rich oils. But between romantic poplars, unpopulated expanses, and quaint frontier homesteads, Dixon’s anonymized portraits of Indigenous and Hispanic people—which bear titles like Mexican Girl (1929) or Paiute Man (1929)—demarcate the erasure of entire populations in established narratives of the West.

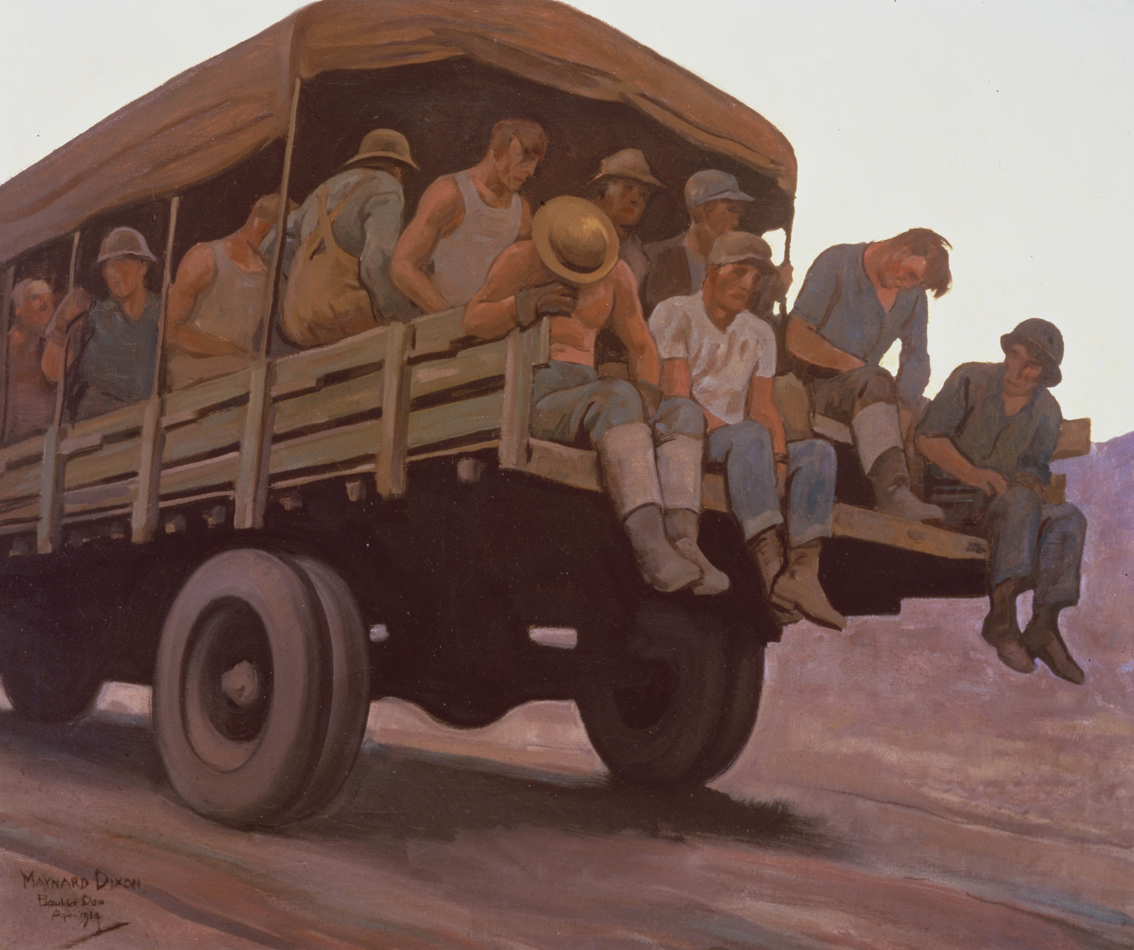

By contrast, portraits depicting Anglo subjects are titled with more personal designations like Old Bill or with the individual’s full name. In Men and Mountains (1933), the artist altered a work that originally depicted Native Americans to feature Boulder Dam construction workers in the foreground of an endlessly receding mountain range. A large self-portrait of Dixon paints the artist as his adopted cowboy persona atop a rearing horse. On the canvas, a misspelled Spanish phrase reads “bien venido y adios!”

Nostalgic in his own time for what he saw as a disappearing “Old West,” Dixon helped visualize sublime landscapes that laid the backdrop for those still longing for a “Wild West” that never really existed—empty, for the taking. Tasteless in its dishonesty, such a narrative remains ornamented in fantasies of an unpopulated Western landscape that informed ideas of Manifest Destiny. Today these narratives make it easier for those who feel entitled to that fictitious frontier to enter their local saloon—bar—and complain that people are speaking Spanish in states with names like Nevada and California (themselves remnants of another colonial era).

For me, Maynard Dixon joins the countless numbers of artists… who chose not to share with us Indigenous people’s identity or story… Art is our history book too and so much history was lost by leaving out a big piece of the narrative.

The exhibition’s curator and contributing scholars are well aware of Dixon’s failure of honesty, and offer it thoughtful consideration in the accompanying book. However, most of this analysis will run you $95 rather than being available via the exhibition itself, although some portraits in the exhibition do offer additional plaques posted beneath the paintings’ title cards that offer pushback to Dixon’s narrative from local Native and Mexican Nevadans.

“For me, Maynard Dixon joins the countless numbers of artists… who chose not to share with us Indigenous people’s identity or story… Art is our history book too and so much history was lost by leaving out a big piece of the narrative. Let’s not proceed that way in the future,” reads one of these plaques, written by artist Melissa Melero-Moose, a member of the Fallon Paiute-Shoshone Tribe.

When institutions like museums look back at the American West, it is worth asking whether the visual narratives they put forth reinforce those they purport to critique, and if they are doing enough to amend historical records re-communicated today. In the case of Sagebrush and Solitude, the exhibition itself falls short of being as honest or modern as its organizers may have hoped.