Mavasta Honyouti debuts sixteen remarkable panels bearing ancestral memories of the Native American boarding school system at Wheelwright Museum.

SANTA FE—As a child, artist Mavasta Honyouti (Iswungwa, Hopi Coyote clan) often accompanied his kwa’a (grandfather) to the family cornfield, where he carefully tended to each burgeoning stalk. Honyouti would unenthusiastically pitch in by helping to hoe weeds and thin plants. For a young boy, these chores were menial—he’d often take long breaks to toss rocks and hide in the shade of the pickup truck tailgate.

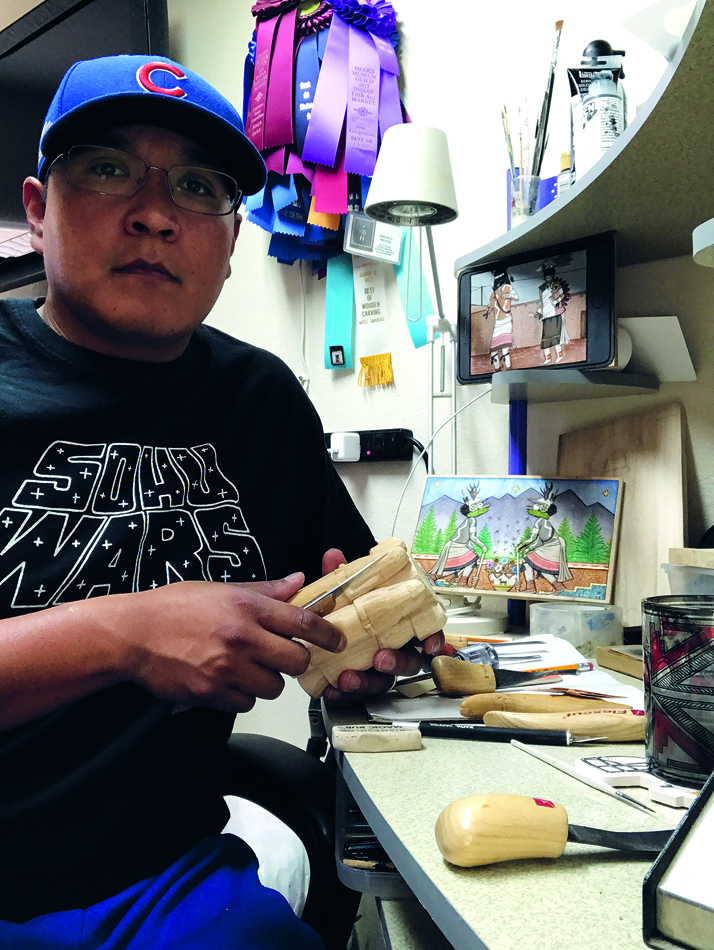

During lunchtime breaks, Honyouti would look on as his kwa’a whittled away at paako (cottonwood root). He did not know that these “hot and boring” days would provide him with the foundational techniques for his carving practice. These childhood experiences would one day culminate in a larger, deeply personal project testifying to his kwa’a’s early years at residential boarding school.

Honyouti’s solo exhibition at the Wheelwright Museum in Santa Fe, Carved Stories by Mavasta Honyouti, features never-before-seen artworks that draw upon familial influences and Hopi lifeways. The multidisciplinary artist and acclaimed Hopi katsina carver has evolved his practice to encompass low-relief carved panels, or plaques. The show features over thirty recent works, sixteen of which are panels and linked to his book Coming Home: A Hopi Resistance Story (2024).

Honyouti hails from Hotevilla-Bacavi, Arizona, on the Hopi Reservation. He is the son of Ronald Honyouti and grandson of Honkuku (Clyde) Honyouti, both celebrated artists. At the Wheelwright, viewers are guided through scenes from the family’s farm.

“I knew our field was important to my family because it was where we would come together, and everyone was involved,” Honyouti says. “I would see them again when it was time to harvest the crops. In between, it was just Kwa’a: he was there every day, at every stage. […] I realized how important every single stalk or plant was to him. Because of his care, patience, and love, we always had a bountiful harvest.”

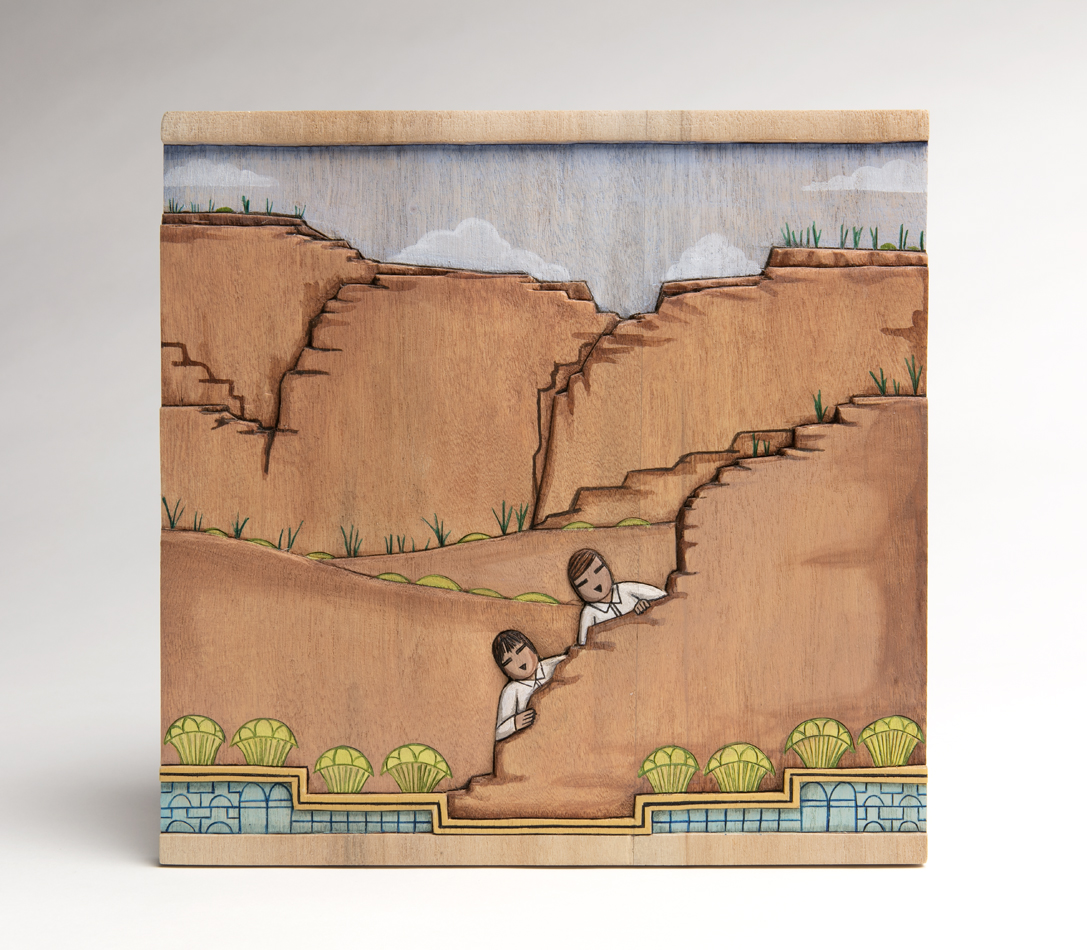

Then Carved Stories jumps further back to when Honyouti’s grandfather experienced the journey as a youth to—and through—Keams Canyon Boarding School in Arizona.

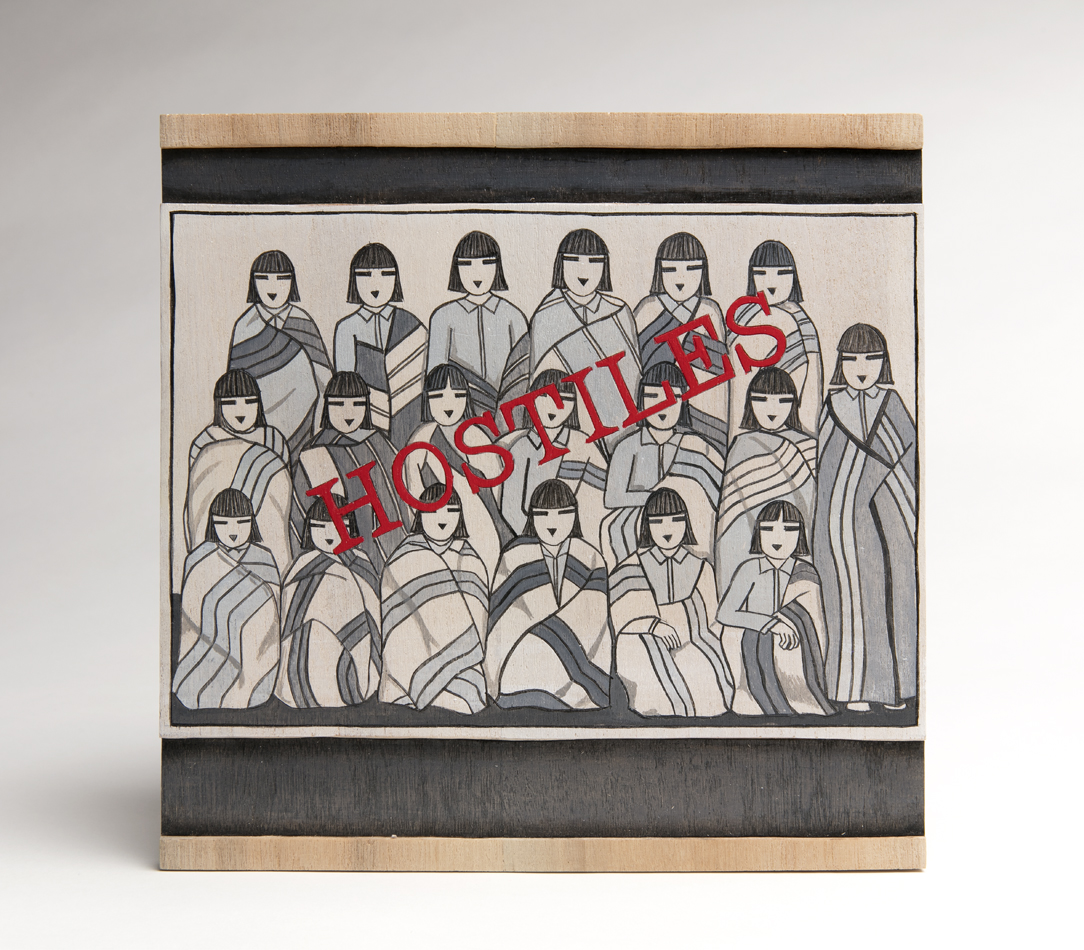

Beginning in the 19th and 20th Centuries, the U.S. government instituted policies with the aim of assimilating Native children into settler culture. A disturbing reality is that to establish boarding school systems, those in power at both local and national levels often abducted children from their families. One day, unable to hide beneath a pile of blankets and sheepskins in his home, Honyouti’s grandfather was forcibly relocated to Keams Canyon with others from his village.

The works chronicling Honyouti’s grandfather’s experience are part of the Coming Home series. Residential boarding schools existed across the United States in figures numbering over 500. By the 1920s, more than 60,000 children—nearly 83 percent of the Native youth population—were to experience this government-funded, commonly church-run, system, according to The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition.

I cried tears of sympathy for those children who were impacted severely, but I also rejoiced in their resilience.

Curator Will Riding In explains, “[The exhibition] provides an opportunity for visitors to learn about one person’s experience [of the Native boarding school era], although there are hundreds of thousands of other stories out there. I felt a close connection to this story as my paternal grandfather had a similar experience like [Honyouti’s grandfather] Clyde did at boarding school.”

Honyouti continues the traditional Hopi katsina practice of carving from cottonwood root, but rather than utilizing mineral pigments, he adopts the modern practice of applying acrylic paint to his plaques. The expanded palette allows the artist to communicate symbolically in his images.

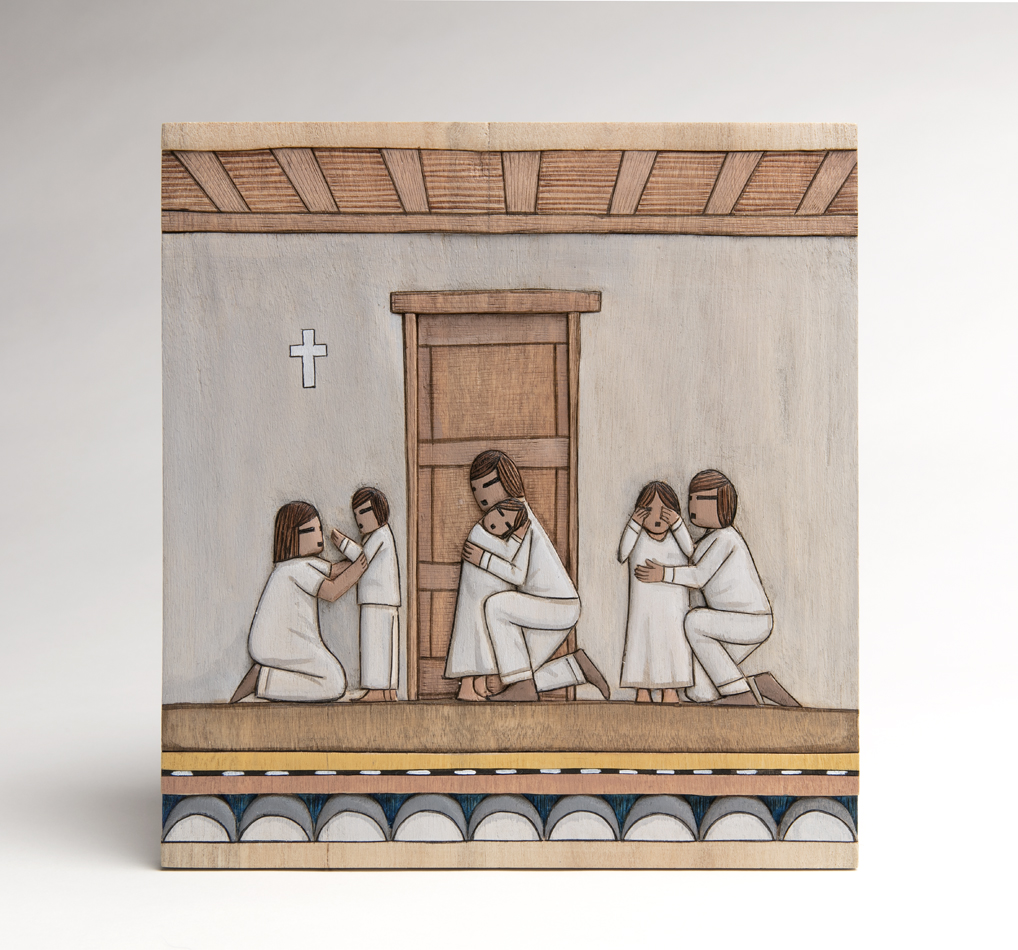

For example, Panel #12 features cool grays and an overall subdued saturation, casting an ominous mood. The piece shows Clyde and his peers kneeling for prayer before bedtime. For many children in this setting, Christianity—a foreign and unfamiliar religion—was imposed upon them, and speaking anything but English was punishable. Children were beaten, starved, or otherwise abused when speaking their Native languages or otherwise deviating from the boarding school program. Some lost their lives, never to return home.

“The title piece was the first that I completed from the set… [and] the imagery evoked powerful emotions for me,” says Honyouti. “I cried tears of sympathy for those children who were impacted severely, but I also rejoiced in their resilience.”

Honyouti also finds moments in the show to uplift Native healing against intergenerational trauma: he encircles otherwise tragic scenes with frames that intervweave colorful Hopi motifs and his own prayers for the children, both survivors and those taken too soon.

The artist says, “Placement of certain symbols, colors, or other details was intentional in each piece.” Some compositions exemplify “strength or resistance,” while “others were reminders of the families that prayed for their safety, guidance, and eventual return home.”

Through his creative practice and his role as a middle school social studies teacher on the Hopi Reservation, Honyouti seeks to empower his students by emphasizing traditional knowledge, practices, and cultural pride.

“I shared the stages of the [Coming Home] book art and story with my students,” says Honyouti. “They were the first to see the complete set in person and when the book was released, they were excited just as much as I was. They cheered when I read Coming Home on its release day. […] I am blessed to experience these journeys with the important people in my life.”

Carved Stories also features colorful, intricately carved works from other Honyouti family members: Ron, Kevin, and Richard. The intergenerational display is fitting, as none of it would be possible without Honyouti’s kwa’a’s return home.

Native boarding schools are not merely in the past—they are a living memory. Contemporary Hopi artists such as Honyouti have learned the story from previous generations, and steward it for future generations. They document both the sorrow and survivance, aspiring to break cycles and affect transformative change—a Hopi resistance story.