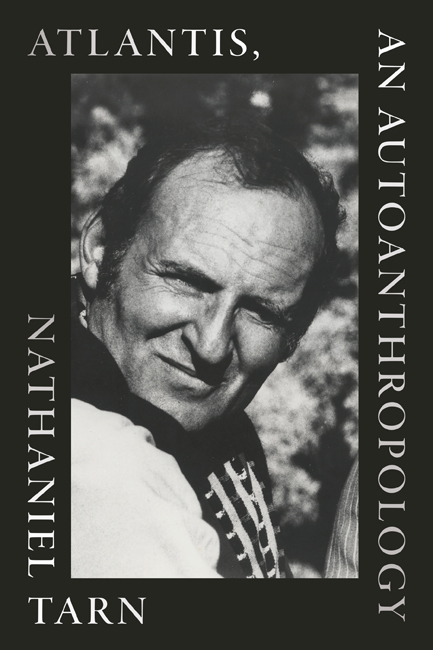

Based in Santa Fe since the early 1980s, Nathaniel Tarn has spent his career chasing an international literature. A new autobiography, Atlantis, an Autoanthropology, explores the author’s broad career.

Sharing an afternoon with Nathaniel Tarn expands life’s possibilities. Both a major poet and anthropologist, Tarn’s stories take him from Les Deux Magots, the famous artist café in Paris, as a twenty-year-old, translating Neruda as a thirty-year-old, then into Guatemala and Burma for field work, then onto a mountain top in Canada to do a reading with Kenneth Rexroth, and on and on until he and his wife Janet Rodney settled in Santa Fe in 1985. They continue to live just enough into the wilderness to complain about the parking downtown.

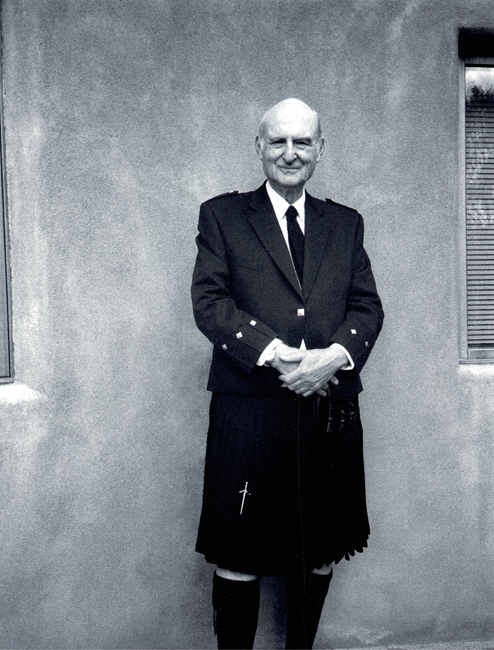

Tarn turned ninety-four at the end of June, but this hasn’t slowed his output. In the past year he has released three books: the long poem The Hölderliniae (New Directions), a translation of the selected poems of French poet Jean-Paul Auxeméry (World Poetry Books), and he has just put out an autobiography, Atlantis, an Autoanthropology (Duke University Press). Tarn has been working on Atlantis since the 1970s, and besides allowing the reader access to Tarn’s many comings and goings, the book acts as a long-form essay on poetics, told from the point of view of a life dedicated to poetry. As with all of Tarn’s work, Atlantis is eminently readable, filled with an erudition based in the world of experience rather than theoretical arguments.

My family and I left Santa Fe for the UK in late May, and so I unfortunately had to conduct this interview with Tarn over email. I miss him immensely, not to mention the delight he takes in both French pastries and mushroom taquitos.

You write in Atlantis, an Autoanthropology about finally settling down in Santa Fe: “I believe that the minute you put down a desk in a place, it ceases to be paradise. Banalizing begins. However, I continue to find the landscape enchanted, and the view out of my study window is a permanent miracle.” How has the landscape—or other aspects of the Southwest—entered your writing since you moved here in 1985? And does it still refuse banality?

Moving from the East Coast to the Southwest: it was an attraction which had begun while following my boss, the century’s great anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, at his lectures on Southwestern and Northwest Coast Native myths at the Collège de France in Paris. My wife Janet Rodney and I had come up from my third field work in Atitlàn, Guatemala, all along the Mexican West Coast seeing some twenty archaeological sites on the way. As we got close to Santa Fe, I said to Janet, “How would you feel about living here?” She said, “I have had eighteen years in Spain and this looks like it.” To me, it imitated paradise away from the cities I had always lived in.

When I got to Santa Fe in the early 1970s as a visitor, there were two excellent bookstores with the right books, some people who knew my work, the presence of Jerome Rothenberg, Dennis Tedlock, and others related to poetry and Mayan lore, some poetry readings, etc. It was extremely lively. By the time my wife and I settled, all this had died down and there was very little contact between local folks and ourselves. It has stayed that way.

I loved the vegetation, even if eventually I wanted more light green than the piñons provided. One huge drama with the bark beetles, from which I had an important set of nine poems: “Dying Trees” in the book Ins and Outs of the Forest Rivers. Every year I have hated the snow and waited for the light green on Tesuque’s P.O. road—my favorite P.O. in the world. There were marvelous green encounters all over the state and Colorado when visiting the archaeological sites whose names, at ninety-four years old, I have begun to forget.

Though perhaps, in time, love has shifted to blue in the sense that there is no greater and more fantastically designed cloud assembly than that above Santa Fe, whether grounded or flying. If I were a photographer, I would do nothing else but go out every day early to see and catch the heavenly array. And to think of how swiftly gone these miracles can be!

You mention studying under Lévi-Strauss, and then your field work in Guatemala. Do your anthropologist-brain and your poetry-brain overlap? Infect one another? Your essays on poetics are clearly influenced by your wide reading of anthropological material (among other things), and you try hard, in the little of it I’ve read, to make your anthropological writings as literary as your poetry. If poetry is your daily food, what is anthropology for you?

This question of Poetry and Anthropology is involved in my nationalities. When leaving Cambridge at the end of World War Two, I decided that I still loved France, where I had been born and so I went back to study there. I was trying to write poems in French influenced by French poets. Suddenly, I heard of the Musée de l’Homme, a major museum and classic anthropology center, and went there. I found I could take classes and that began two to three years at the museum, the Sorbonne, and the Collège de France: most of these anthropological.

As I went, two problems arose. One: there did not seem to be many jobs in France. Two: the immersion in French was not working well for, amongst other things, everyone I knew spoke English also. In short, the question became do I really want to be a French poet or will it be English? As I came to Yale and the [University] of Chicago for anthropology, English prevailed even more. Although I had to work hard for a doctorate in anthropology, poetry never went away but there was no time for it and so poetry worked inside me during first field work at Atitlàn with different notebooks, one for anthropology, one for poems.

Had I known more about the American poetry scene, I could have gone to Black Mountain College in the U.S. run by a poet I had begun to follow—Charles Olson—but as a Fulbright scholar I had to go back where I came from. For all sorts of reasons—family, an English life I had had, and a girl—I went back “home” to London. This ended in more anthropology at the London School of Economics, my being sent for field work to Burma, and a job teaching at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London.

Literature and primally poetry could be an interest of everyone instead of a small activity engaged in only by a few people whom in most cases are considered to be weirdos. —Nathaniel Tarn

Poetry suddenly appeared in Maymyo, a small Burmese village, where I was attracted to its botanical gardens. On one morning there, inspired by the green beauty, I suddenly wrote a suite of poems. Also, there was a fine Canadian poet (David Wevill) working in Mandalay when I worked there. When we were all back in London, David took me to a group formed by a number of leading Londoner poets. There were also contacts with publishing people and my first book got born, Old Savage, Young City (a title I would not use today), and then came other things like translating Pablo Neruda: I became one of the early translators of that master.

Eventually, I felt that anthropology was actively over and that poetry had to dominate. And it was American poetry since Olson, [Robert] Duncan, Denise Levertov, [George] Oppen, and my wife Janet Rodney out of many. In 1972 and later, I acquired a third nationality, teaching at Princeton, Philadelphia, and Rutgers and being published in the U.S. There was a little more anthropology when a young British archaeologist arrived at Rutgers. He specialized in Maya cultures. Soon, I was remembering Atitlàn and looking for a language which would be totally responsible to science but, by avoiding jargon, would not leave out one blot of literary value. This became the result of the third Atitlàn fieldwork: the book Scandals in the House of Birds. So it is that the outward-looking anthropology lived with the inner-looking poetry for a long time and it all has remained so. Eventually, Poetry took over totally after teaching in China and has been my Lord-and-Lady power ever since.

Knowing you mostly through the high desert, I love imagining you coming to a suite of poems through the greenery of Maymyo. Neruda! You’ve talked often to me about your ideas about international literature being what drives you—the possibility of being in dialogue with an international poetry being important to your writing. And yet you still ground your poetry in what might (too easily) be called poetics after Olson—famously anthologized in Don Allen’s The New American Poetry 1945-60. I don’t think these two things are in opposition, but what about poetry and poetics from the United States at that time allowed (allows!) you to think internationally?

There is no real need to separate interests in World Poetry and Local/National Poetry. My knowledge of the goings-on in American poetry were mainly aroused while still living in London (which had a first-class poetry shop with as much American poetry as you could find in the U.S. itself), with occasional trips to the U.S. where buying and collecting continued: for instance, in New York at Eighth Street and at City Lights in San Francisco. Among much else, I was fascinated by an element Charles Olson was interested in: the sheer size of the U.S.—of the Americas indeed—and the challenges this created for, specifically, poets. The size indeed became the major attraction for me as I worked less and less on individual poems and embraced the long poem as practiced by the likes of Olson in lieu of the short poem still embraced by the Anglophiles.

Then there is interest that an Olson could awake when working with the poetry of Australian Natives and the Maya in Yucatán. Out of such efforts, there emerged a sense of extreme care and custodianship of place against colonialism’s miserable squeezemouse attitudes to a country’s Natives.

It is less easy to describe what an international sense of literature and specifically poetry would feel like. On the one hand I recognize that humans have still not gotten rid of “nations” with all the beautiful but also terrifying responsibilities this places on human shoulders. I follow the great Indian writer Arundhati Roy in believing that nations eventually may be the end of us: look at Russia and Ukraine right now. As things stand we cannot do away with the feelings, often loving, that people belonging to a country feel towards that country.

When poetry is concerned however, similar feelings and interests come up about French poetry, or German, British, Italian, Spanish, Russian, Chinese, Japanese poetry, etc. This can leave one behind the primal fact that poetry is international, world-wide as well as very ancient (remember Homer for one). It is the academic world and especially the departments of X literature, Y literature, Z literature which very often restrict a human being in his or her knowledge of this imperial art on a world basis. The “discipline” of Comparative Literature is but a very small beginning. However, we have Translation and it is abundantly available. Poets could move more around in the world and could partake and give—organization and expenses laid out—of the universal joy which poetry can arouse. Instead of receiving this that or the other “prize” or “award,” those who work hard enough to become masters of art and craft could be called simply “World-poet.” In Spanish, Neruda would have been one. But also someone even greater than Neruda perhaps: the Peruvian César Vallejo. In any event, literature and primally poetry could be an interest of everyone instead of a small activity engaged in only by a few people whom in most cases are considered to be weirdos. I recall that, in the “normal” world, being a poet would be a spare-time activity—if necessary at all—while wealth, money in short, was someone’s primary activity and hunt. It took me a great many years to get out of that one.