The absence of water and its ecological effects are the subjects of an emerging speculative earthwork by the French artist Marguerite Humeau and nomadic art museum Black Cube.

This article is part of our Collectivity + Collaboration series, a continuation of the ideas explored in Southwest Contemporary Vol. 5.

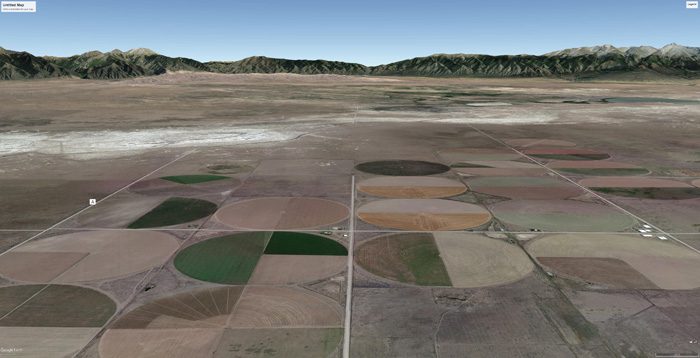

SAN LUIS VALLEY, CO—Drive north from Taos, New Mexico, and the sky will suddenly open up to reveal the San Luis Valley, a vast geological marvel created some thirty-five million years ago by one of the largest volcanic eruptions in earth’s history. With altitudes in excess of 7,500 feet and more acreage than the state of Connecticut, the San Luis Valley is the largest alpine desert in the United States—and the largest alpine valley in the world.

Cradled by dramatic snow-capped mountains and blanketed with fragrant sagebrush, the valley is home to wild horses, the Rio Grande River and verdant wetlands, a UFO watchtower, and natural wonders like the Great Sand Dunes. Colloquially, the San Luis Valley is referred to as the “Land of Cool Sunshine”—350 days of cool sunshine per year, to be precise.

Every year in early spring and late summer, 20,000 migrating sandhill cranes traverse the valley, pausing at the Monte Vista National Wildlife Refuge before continuing on. Ancient Puebloans memorialized this sacred tradition over 1,000 years ago by carving a crane symbol into a rock face, known today as “the Big Bird Petroglyph” (as a matter of protection, the Rio Grande National Forest won’t disclose its exact location).

As magical as this all sounds, however, the San Luis Valley is also an ecosystem in crisis.

Plagued by debilitating droughts, agricultural production in the San Luis Valley has stalled, leaving residents struggling to preserve their livelihoods. To make matters worse, what remains of the valley’s natural water resources is being siphoned off by richer urban communities to the north.

The absence of water and its ecological effects are the subjects of a site-specific, speculative earthwork by the French artist Marguerite Humeau.

Produced together with Black Cube, a nomadic art museum headquartered in Denver where she’s currently an artist fellow, Humeau has entitled the project Orisons, an ancient word for “prayer.” She describes it as an “offering” to the valley. Two years in the making, the work’s public opening is currently slated for the last weekend of September 2022.

Humeau’s canvas is a 160-acre plot of fallow land in Hooper, a town adjacent to the sand dunes nature preserve with a population just shy of 100 (as of 2019). The land was donated for this project by Jones Farms Organics, a fourth-generation organic potato farm that is water-neutral. Cortney Lane Stell, Black Cube’s executive director and chief curator, explains that Orisons developed out of conversations with Humeau about her bodies of work that deal with weeds and water resources.

Humeau was born in 1986 in France and is currently based in London, where she earned a master’s degree from the Royal College of Art in 2011. Since then, she’s had solo exhibitions at institutions including the New Museum, New York (2018), Tate Britain, London (2017), and Palais de Tokyo, Paris (2016). Her work is currently featured in the Venice Biennale’s exhibition The Milk of Dreams.

Humeau has a research-based practice that manifests in hyper-speculative and surreal installations. “My work is about reconnecting with a sense of spirituality,” Humeau says, “creating portals for other worlds, connecting to the ancient past, to speculative futures and, maybe, to alternative presents.”

Her art samples the space-time continuum, from archaic societies to the multiverse of science fiction. “I think that’s what art is about—when it originated in prehistory,” she says, “to connect with spirits and communicate across life forms.” She points to the Big Bird petroglyph as an example and its existence today as a symbolic bridge to our ancient selves.

During Humeau’s Black Cube fellowship, she and Stell discussed ancient plants as kinds of proto-connection to primordial species and a source of spiritual healing, recurring themes throughout Humeau’s work. For this project, Humeau was interested in working with natural materials, unlike the resins and other synthetic mediums she’s previously employed. Another goal was to ultimately produce a work that could be seen from both the land and the sky.

Black Cube projects tend to feel anomalous within an artist’s practice, “and that’s something we do very intentionally,” Stell says. “We want to propel artists to think about sight and audience differently. We want to grow their practice, we want to challenge them in some way.”

Together, they settled on the San Luis Valley as a potential site and began outreach to local communities. “An important theme in my work has always been collaboration. I’ve been thinking a lot about how the wind collaborates with the weeds, which collaborates with the water, with the farmers and human communities, with the birds, and so on,” Humeau says. “So, the work will be about these connections and how to activate them even more.”

Black Cube’s site-specific projects embrace the responsibility that accompanies public art. “We don’t want to do plop art,” says Stell, “so we spend a lot of time figuring out who we need to talk to, and making those connections.” For this project, Humeau and Black Cube met with farmers, soil scientists, water conservationists, policy-makers, Indigenous members of the community, ornithologists, ranchers, and other members of the agriculture industry.

Stell points out that Colorado’s first water rights originated in the San Luis Valley 170 years ago with the San Luis People’s Ditch—an irrigation system comprised of more than seventy acequias (essentially streams fed by the mountains’ melting snowpacks)—that’s communally owned and operated. This system, however, is currently under attack from both climate change, which has lessened snowfall and precipitation each year, and development-hungry speculators.

The counties that comprise the San Luis Valley are among the most impoverished in the state. Economically speaking, they could certainly use the money offered by bigger cities for their water rights. However, Stell points out that these communities have united against the corporations and private concerns trying to export their water for profit.

“They understand that their water is more valuable than money,” Stell says. “So I think that is also an important aspect with this work—this valley is an extreme microcosm for that water struggle that I think we’re all feeling in the American West. In that way, it’s also a microcosm for climate change.”

Earthworks have a storied history, especially in this part of the country. This critic would argue that some suffer from the delusion of manifest destiny, channeling a type of pioneer spirit that’s problematic at best. Eyewitnesses have lamented that Nancy Holt’s work Sun Tunnels feels like a rave during the equinox, while iconic installations like Walter De Maria’s lightning field are disproportionately difficult to access.

Humeau’s earthwork, which is expected to be on display for two years, promises to invoke a more nuanced appreciation of its site-specific contexts: environmental, political, economic, and spiritual. In doing so, her work seeks to terraform an updated genre of “the earthwork,” one that’s attuned to its surroundings and their myriad interdependent relationships.

This ambition recalls the words of philosopher Donna Haraway, who championed an “ecology of practices” and writes in her book Staying with the Trouble, “The biologies, arts, and politics need each other, with involuntary momentum, they entice each other to thinking/making in sympoiesis for more livable worlds…”—precisely what the San Luis Valley urgently needs.

To stay updated on Orisons, follow Black Cube on Instagram.