Though focused on a 20th-century photographer, Manuel Carrillo: Mexican Modernist illuminates a sense of community identity through beauty that connects to the work of artists practicing in the Southwest today.

“Affection”—“sensitivity”—“compassion”—“grace”—”humanist”—“truth”—“curiosity”—“respect.” These are some words several journalists, critics, and peers wrote to describe the photography of Manuel Carrillo in the modest scholarship written about him.

The New Mexico Museum of Art’s current exhibition Manuel Carrillo: Mexican Modernist provides a concise introduction to the lesser-known photographer, who portrayed his country as it evolved during his lifetime, turning his lens to raw moments in local and Indigenous cultures. In a contemporary world battered with divisiveness, the artist’s street photography unveils a fresh sense of unity. The show—on view through February 4, 2024, and mounted as a small display in an upstairs gallery—also offers avenues for further inquiry into the artist and thematic connections to photographers working in the Southwest today such as Delilah Montoya and Maryssa Rose Chavez.

Though a peer of celebrated modern photographers Manuel Álvarez Bravo and Edward Weston, Manuel Carrillo (1906-1989) was considered an amateur hobbyist, which turned out to be an unlikely benefit recognized by his admirers. Working in the railroad business, Carrillo didn’t exhibit his photographs until he was forty-nine. His peripheral role in the Mexican photographic “art world” translated as a sense of familiarity, even intimacy, with his subjects. Manuel Carrillo: Mexican Modernist prioritizes this notion, focusing not on how Carrillo fits into art historical discourse, but how he stands out.

Carrillo did create in a Modernist style, playing with light and shadow to capture geometric forms. However, walking out of the exhibition, I felt Carrillo’s artistic voice was less ascribed to Modernism than dedicated to social photography of—and with—his people, for whom Modernism depicted them with a sense of beauty.

There’s nothing deliberately sophisticated about his images in the show, which groups objects into simple themes such as “animals” and “street photography.” There are scenes of children playing baseball, a mother breastfeeding, an overwhelming crowd of dogs.

“Carrillo was a photographer who sacrificed the comfort of the studio for the spontaneity of capturing life as he encountered it outside,” says David Scheinbaum of Scheinbaum and Russek, a Santa Fe photography gallery that has offered Carrillo’s work for several years. The artist has a clear connection with local communities, understanding that to capture these people he must immerse himself in their worlds. “[Carrillo] sees with the eyes of the humanist, for whom all people share a common life and role, and we feel as though we are there with him,” the Santa Fe Reporter wrote in 1981.

The unabashed affinity of Carrillo’s artwork recalls two contemporary photographers in the Southwest, Delilah Montoya and Maryssa Rose Chavez. All three artists demonstrate how the camera is a tool that can illustrate a level of closeness among people despite cultural tension, economic struggle, and personal grief. In doing so, they visually define broad and familial cultures and challenge documentary photographic traditions. “He’s seeing the other world,” says Montoya about Carrillo. “He’s going right after the Indigenous folks, looking at them when most people ignored them.”

I initially reached out to the Albuquerque-based Montoya, who taught at the University of Houston, to discuss her work because I noticed a link between her practice and Carrillo’s. Known for her exploration of Chicana identity in the Southwest, Montoya is interested in how photographs illuminate or conceal through presence. Referencing conventional documentary camera work, she says, “Even if there are no figures in the shot, I’m here, we’re here.”

Carrillo struck a chord with Montoya, and our meeting developed into her analyzing his work. This proved fascinating, as several of the points Montoya made about Carrillo are like those I would make about her photography.

Montoya observed that Carrillo “is focused on finding Mexican nationalism, saying Indigenous Mexican identity is worthy and valuable.” Montoya’s current project, Contemporary Casta Portraiture, reconsiders 18th-century Spanish colonial paintings that explicitly portray hierarchies of class and race by re-envisioning the images with Chicano subjects.

Incorporating multimedia elements, her project complicates notions behind casta portraiture from different angles. Montoya has taken sixteen family casta portraits and processed DNA analysis for the sitters. The prints are juxtaposed with a map illustrating the subjects’ ancestral migration as well as test tubes filled with colored sand to visualize biogeographic heritage. Each work also has a QR code that links to a family member speaking about their portrait and DNA analysis. In this scientific approach to creative work, Montoya asks, “Who defines who’s valuable in society, and why?”

“I don’t want to make things that are just legible to the public. I want to make work for the people I’m making them of,” says Maryssa Rose Chavez, whose practice is grounded in family. Growing up in Española, New Mexico, with her family living in Pueblo Territory since time immemorial along the Rio Grande River, Chavez has been interested in her family story since childhood.

Coming of age in a town with a multigenerational family who struggled with substance use disorder, she says, “There’s been a lot of secrecy coupled with shame and guilt, but no one was asking questions. So, I became the record keeper. I felt a desperate need to photograph because there was a lot of loss.” There were oral histories passed down, but she picked up the camera to preserve traditions in a new way, asserting, “There’s something to be said visually about their experiences.”

Chavez’s Plebe Under Ocean (2020-21) is a suspended quilt printed with cyanotypes of the artist’s family on one side and a self-portrait on the other. Remembering stories from her grandfather about the prehistoric Española Valley Basin being the bottom of an ocean, Chavez made the textile blue.

Plebe Under Ocean demonstrates the importance of her lineage: the quilt is as long as the artist is tall, so she can wrap herself in her family. Her current project, parts of which were on view at The Valley in Taos last summer, studies the connection between earthen objects and the home; her grandmother avidly collected rocks, her grandfather built homes of stone, adobe, and worked in limestone plaster, and the home of Chavez’s maternal and paternal grandparents were made by her grandfather’s hands and of earthen materials such as adobe and rock. “Making an adobe is like making a fossil,” she says. “It’s crazy to have objects today that have sustained my people for generations. The earth, as home, is where this newer work’s inspiration comes from.”

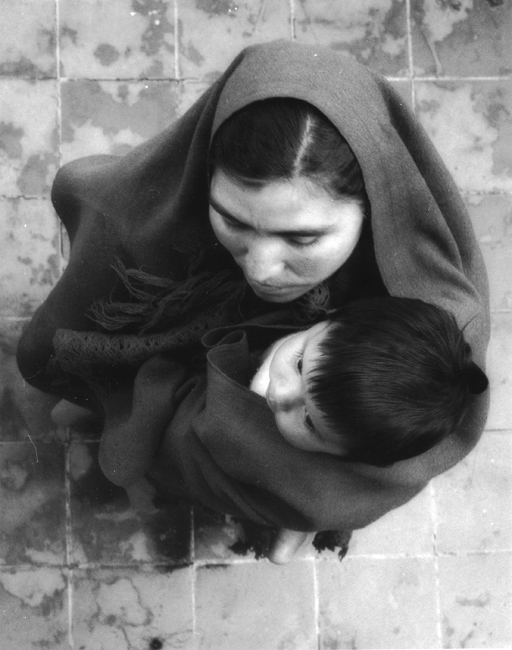

Carrillo’s work takes a similar tone, making work not for the art-viewing audience but for the subjects he photographs. In Untitled (1961), Carrillo captures, from above their heads, a mother carrying an infant in a blanket; the figures look forward, away from the camera. Shot from a strange angle and heavily cropped, the image emphasizes the blanket’s round shape when draped over the mother’s head and swathed around the child’s body, the ends meeting in between the figures. The composition metaphorically depicts the blanket as a shield connecting and protecting the two figures, as if in a cocoon. This photograph embodies how Carrillo’s practice “is informed by a special kind of love,” a reflection once made by El Paso educator, critic, theater director, and actor Joan Quarm about the artist.

There is something to be said about creating from a position of love. It produces work that is relatable or accessible regardless of the viewer. Montoya’s earliest work was motivated by the differences between her undergraduate academic setting and the Chicano art community where she lived. She was inspired by the love she felt for each environment, curious how they compared. Chavez’s desire to visually record her family amid loss comes from her deep love for them, the grief she carries, and the healing she seeks, all to hold Española close while making space for the life she has cultivated in Austin, Texas. Carrillo’s photographs, Quarm once said, “Enrich not only his own country but the entire human race” because of love. I would argue the same about Montoya and Chavez.