Mallery Quetawki paints cross-cultural translations that help bridge futures between Indigenous communities and science and medical professionals.

“We can’t put a Band-Aid on historical trauma,” reflected Zuni painter Mallery Quetawki in June in Albuquerque. She moved down a narrow hallway lined with several of her electrically colored acrylics on canvas, compositions that alloy Indigenous protection symbols with the language of biological and medical illustration.

Born and raised “as traditionally as modernly possible” on Zuni Pueblo, Quetawki was nurtured by potters, fetish carvers, and jewelers. Later, at the University of New Mexico, she earned a biology degree, minoring in art. This pastiche of experience directly informed Quetawki’s uniquely intercultural aesthetic. In recent years, she’s danced between worlds, showing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the El Paso Museum of Art in Texas, and the IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts in Santa Fe, vending paintings and ceramics at Zuni Pueblo, and contributing illustrations to the covers of two different medical journals.

We ducked into an air-conditioned office and relaxed on comfortable rolling chairs around a laminate table. It was a Tuesday, so Quetawki was at work at UNM’s College of Pharmacy. In 2017, while serving as a patient care technician at the university hospital, Quetawki was offered an experimental artist-in-residence position in UNM’s Community Environmental Health Program (CEHP). Dr. Johnnye Lewis contracted Quetawki to produce original paintings translating scientific and medical information for the Center for Native American Environmental Health Equity Research, which focuses on uranium and other mine waste exposure on tribal lands. Like so many American institutions, UNM was struggling to effectively connect with Native communities. Quickly, Quetawki’s hybrid vocabulary resonated with Diné, Pueblo, Crow, and Cheyenne River Sioux groups whose landscapes and physical bodies have been poisoned by the Cold War nuclear weapons chain. Within a year, Dr. Lewis brought Quetawki on full-time as CEHP communications and outreach specialist. The paintings have remained part of the job.

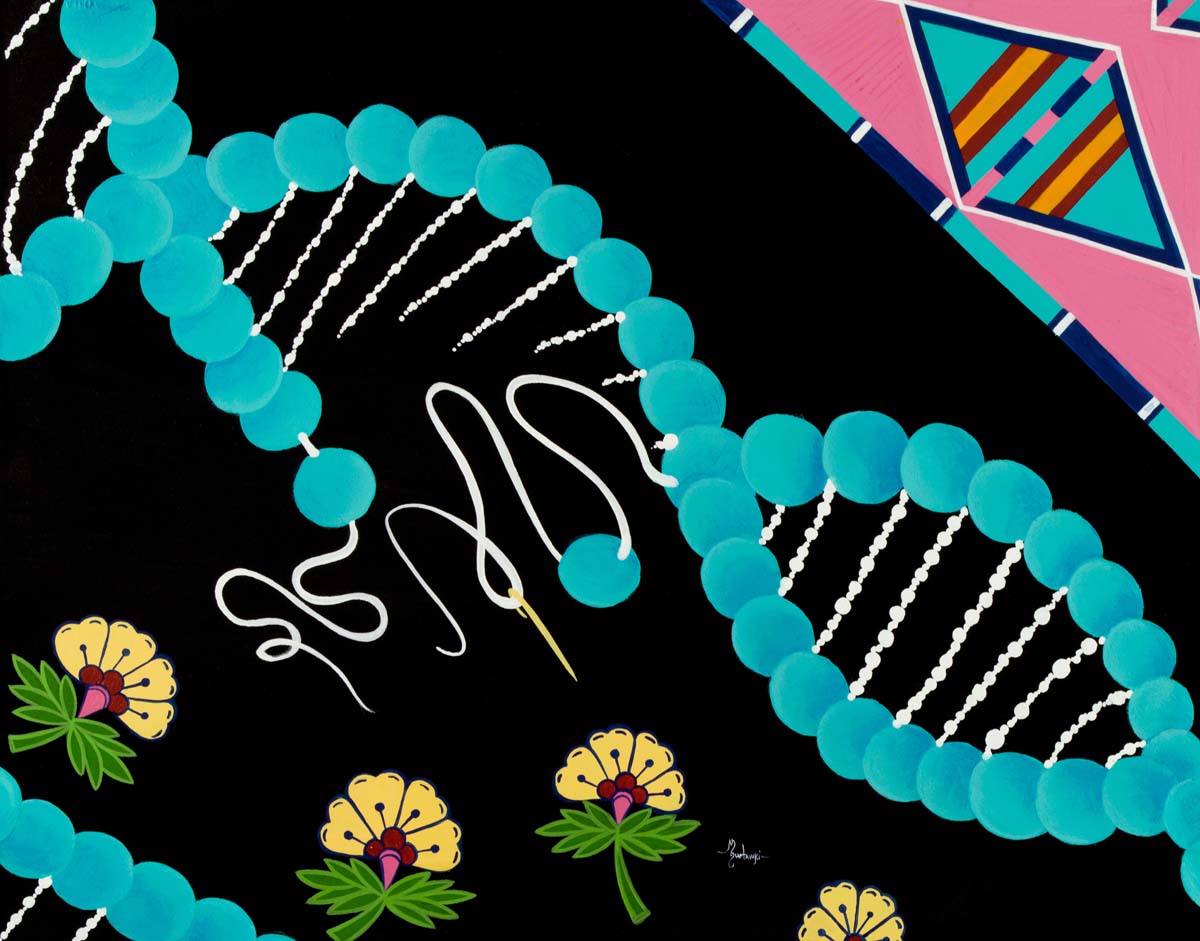

Immune Response (2017) and Autoimmunity (2018) depict human cellular networks in ways that can be understood scientifically, but also culturally and spiritually. Navajo wedding baskets, Plains medicine wheels, shocks of turquoise, and buffalo, war ponies, and bears represent the body’s pathogen-fighting B cells, T cells, and macrophages. In All My Relations (2018) and DNA Damage (2017), beaded necklaces recall genomic sequences, with disruptions in their intricate patterns pointing to mutations.

Simultaneously, Quetawki introduces scientists and medical professionals to the complexities of traditional ecological and biological knowledge, challenging them to confront historical traumas enacted not just by extractive industries and duplicitous governments, but also by institutional research. Potential futures guide her studio and outreach work, but where other artists wield speculative or science fictional strategies to imagine more just futures, Quetawki’s world-building is more local, chronologically speaking.

“Institutions have to make policy changes,” said Quetawki, pausing to look around the office contemplatively. “Universities, hospitals, and industry must become willing to build their capacities in ways that complement capacities that have long existed within our tribal communities.”

Always practical, Quetawki still finds ways to bend space and time. Consider Extraction and Remediation (2020), which was featured in Exposure: Native Art and Political Ecology, a touring group exhibition that collated multi-hemispheric Indigenous critiques of nuclear colonialism. The fourth-dimensional landscape diptych uses multilingual iconography to narrate overlapping chronologies. Nodding to Pueblo imagery, a red lifeline moves through subterranean, knowledge-recording petroglyphs. A yellow band—uranium—moves in tandem, safely entombed by a shield of turquoise. A double-helix, also turquoise, winds deep, like a harmonic bassline. But as extractive technological circuitry appears, penetrating the earth, the canvas splits, depleting the turquoise. The DNA breaks. Radioactive trefoils escape, eradicating flora and entering the atmosphere.

Here, Quetawki upends the apocalypticism of the moment, forecasting a future of remediation and repair. The Zuni Sunface, an ancient symbol of life, emerges within the circuitry. The uranium is reinterred. Yellow sunflowers—hyperaccumulators used for phytoremediation at sites including Chernobyl and Fukushima—sprout from the landscape. Modernized Pueblo pottery designs protectively surround the rekindled lifeline. The double-helix regains its rhythm.

Universities, hospitals, and industry must become willing to build their capacities in ways that complement capacities that have long existed within our tribal communities.

Last December, UNM hosted the Superfund Research Program’s annual meeting, a gathering organized by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency where top-level scientists, researchers, and policymakers wrestle with the futures of America’s most toxified landscapes. When Quetawki was tapped for a panel, instead of charts and graphs, she brought along reproductions of works by several artists in the Exposure exhibition.

“These are people who might never walk into an art museum,” Quetawki explained.

She also invited Exposure artist De Haven Solimon Chaffins (Laguna and Zuni Pueblos), who spoke about her work, and offered what Quetawki described as a “beautiful but heartbreaking perspective” on devastation and survivance in Paguate, New Mexico, a part of Laguna Pueblo that has been ravaged by the Jackpile-Paguate Uranium Mine, a Superfund site on the National Priority List. For many of the engineers, chemists, legislators, biologists, and toxicologists, this was their first encounter with human testimony instead of anonymized scientific data.

“Afterward,” recalled Quetawki, “they asked us how they could connect with these artists to learn more about Native experiences. We’d pressed the unmute button for them.”

Between her outreach, studio production, and adept navigation through research circles, Quetawki has become a practical speculator, stoking technically feasible near-futures—science realities—where Indigenous ecologies are not just integrated, but centered.