Making Visible at the ASU Art Museum upends white narratives of the colonized West with contemporary ruptures.

TEMPE, AZ—In 1950, Phoenix lawyer Oliver B. James gave sixteen oil paintings by various American artists to Arizona State University in Tempe, Arizona. Over the next several years, he donated hundreds of additional artworks, including paintings by Frederic Remington and Joseph Henry Sharp.

With James’s gifts, ASU founded its University Art Museum, now housed in the Antoine Predock-designed Nelson Fine Arts Center. While the museum’s current holdings of more than 13,000 artworks are richly varied, the permanent collection’s origins and representations have long troubled its curators as the Western art, often featuring Native figure models, promotes a white male cis mythology of a West that’s devoid of women, children, and the Indigenous people living there.

“I’ve worked with the collection for many years, and have come across archival silences again and again that are hard to grapple with,” says ASU Art Museum curator Brittany Corrales. Mary-Beth Buesgen, curator of collections and archives, agrees: “We’ve been examining new narratives we can bring to light while working with the permanent collection, focusing more on social issues than on techniques.”

“A lot of the stories in Western art are manufactured, romanticized, fake, and focused on a mythological past,” adds Ninabah Winton (Diné), Windgate assistant curator of contemporary craft and design fellow at the museum.

“Our research intentions were to uncover the truth, to change the general public’s perceptions of Western art, to tell more of a story than a canonical history,” says Winton about co-curating the ASU Art Museum’s current exhibition Making Visible, on view through July 23, 2023. “I wanted to change the narrative.”

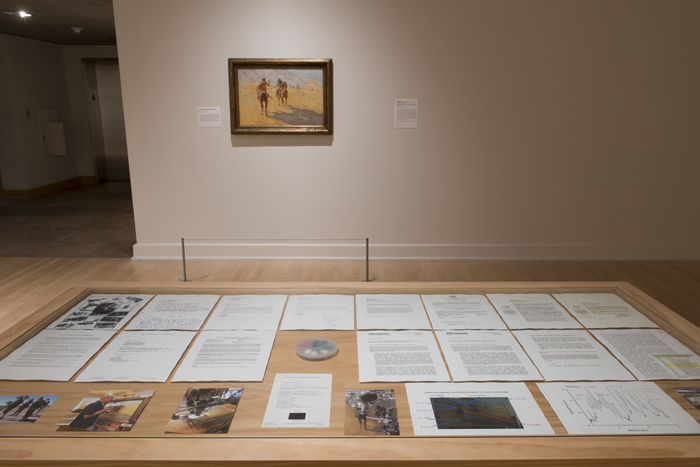

Winton and her colleagues have done just that. Making Visible interrogates works from the permanent collection with new art acquisitions, didactics, audio, video, and gallery columns wrapped in newspaper articles and letters from the accession files. The show essentially subverts the colonial narrative with acute visual ruptures.

Consider, for instance, The Cowboy’s Dream by Arizona cowboy artist Lon McGarvey, the first artwork in the exhibition and one that’s rife with misogyny. In the poorly executed painting, a white cowboy, sprawled on his saddle with his hat over his face, dreams of a naked woman on a horse whose flank is branded with a beer logo. (The image, Corrales explains, was created for a brewing company and mounted in bars and saloons throughout Phoenix.) In response, two photographic self-portraits by contemporary queer artist Chela Rodriguez—with hat over her face—call attention to gender roles, question machismo, and conjure the Vaquero traditions that white American cowboys adopted.

Other works delve into the “invisibilization,” as Winton puts it, of Native models—including Geronimo (Jerry) Mirabal, whose name was anglicized to Jerry Taos—by the Taos School of Painters. Paintings of Mirabal—whether in forest settings, on all fours, wearing buckskin or blankets, hunting, or otherwise projecting the “noble savage” stereotype—are juxtaposed with the explosive 1973 lithograph Portrait of a Massacred Indian by Fritz Scholder (La Jolla Band of Luiseno Indians). An Andy Warhol of Sitting Bull, celebritized and commodified with cartoon-like outlines, is positioned next to a cigar-store Indian princess, whom the curators turned to face the wall. As the archival newspaper articles reveal, much effort was put into finding the white artist who carved her, but not the model.

The exhibition also investigates the romanticization of an uninhabited desert, unrepresented populations including Black cowboys and Japanese interred during World War II, and the absence of children and women in lone male white cowboy mythology. In one vitrine, paperwork demonstrates how a Remington painting was proven to be a fake. A panel on the ways in which the museum is attempting to reach beyond mere land acknowledgement includes information on deaccessing artworks not aligned with the museum’s mission and using the resulting funds to acquire works by contemporary Indigenous artists.

“We had a lot of thoughtful discussions about not reinforcing stereotypes or perpetuating further harm” while planning the exhibition, says Buesgen, “which was a rewarding experience. There’s a point where museums, including ours, need to move forward. We’re doing that through an ongoing process of unlearning.”

Adds Winton, “Having the opportunity to subvert the narratives that have obscured, erased, and otherwise harmed Native people was really exciting.”