Museum of Modern Art, 2017

Louise Lawler has spent her career effacing any presence of her own identity in her artworks.Her works themselves are often either mechanically produced or feature the work of other artists. She has given a total of three published interviews. When asked, in 1990, for a photograph of herself for the cover of a magazine, she sent a photo of Meryl Streep instead, with the words “Recognition Maybe, May Not Be Useful” printed across it. For Lawler’s recent exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Why Pictures Now, a survey of works spanning over three decades, Lawler cleverly reprised that work as a poster with a different image of Streep.

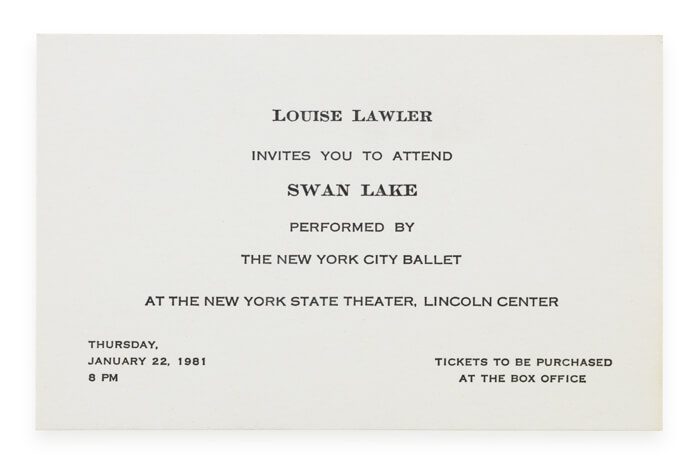

It should come as no surprise, then, that Lawler’s voice in Receptions, the book accompanying Why Pictures Now, is limited to only a brief statement by the artist and a few quotations used by the book’s eight contributors. Because we have little of the artist’s personality to distract us from her copious output, her works have been interpreted in myriad ways, as the book’s essays attest. This, of course, is the endgame behind Lawler’s self-effacement. She is not her subject; the many contexts and frames in which artworks operate are. Sometimes these frames merely comprise the arrangement of artworks in a museum or domestic space, as when she included works by Cindy Sherman, Robert Longo, and others in her first one-person show at Metro Pictures in 1982—or in her famous 1984 photograph Pollock and Tureen. At other times, the framing device becomes abstract. Also in 1982, Lawler sent an invitation to her mailing list implying that if they were to purchase tickets and join her at Lincoln Center to see a specific performance of Swan Lake by the New York City Ballet, they would, in fact, be watching a work of art by Louise Lawler.

Such strategies of appropriation and contextualization are hallmarks of postmodernist art and institutional critique, categories that Lawler’s practice has helped to shape and define. As Receptions makes clear, though, Lawler’s artworks are more relevant than simply as antecedents for these important developments. Her commitment to investigating the complex relationships between art and politics, always a subtext if not outright obvious in her early works, defines her recent projects, notably in a collaboration with artist Cameron Rowland. For a 2016 exhibition, Rowland and the gallery Artists Space commissioned several benches from imprisoned laborers at a correctional facility in New York in order to foreground working conditions in state prisons and the prison system at large. An iteration of Rowland’s work, 91020000, appears as part of Lawler’s MoMA show, and Receptions contains a reprint of the text that accompanied the original installation, which parses the Thirteenth Amendment and discusses its implications for the development of the U.S. prison system after the end of slavery. The inclusion of works by other artists in her own solo exhibition, as an example of art with which she wishes her own work to commune, emphasizes Lawler’s sometimes oblique strategy for engaging political content in her own practice.

Because Lawler’s artworks rely on their immediate contexts and on viewers for their meaning, the same is true for Receptions. The book offers many points of access to think about Lawler’s artworks and how the strategies she has used to jar viewers out of complacency might be employed now. The title of the MoMA survey, Why Pictures Now, is an indication that Lawler intends for her work to function in the present, not as historical artifacts of postmodernism.