As a member of the inaugural cohort of La Semilla Food Center’s Chihuahuan Desert Cultural Fellowship, Juárez-based writer Lorena Sosa shares her work on the U.S.-Mexico border.

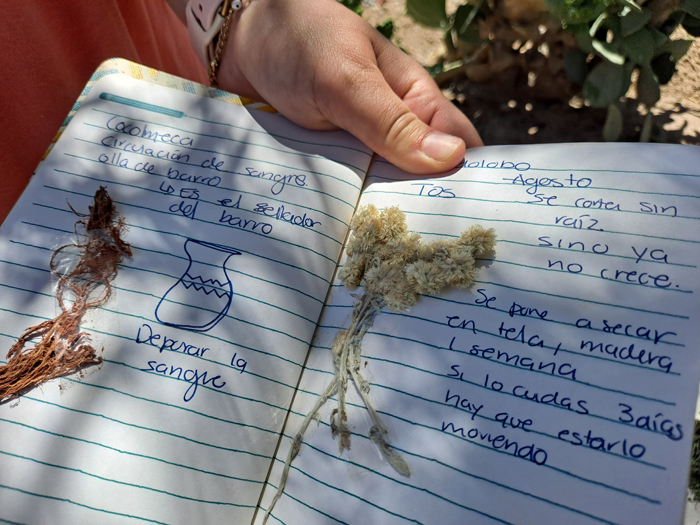

Lorena Sosa is a writer, poet, and educator based in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico. Originally from Chihuahua City, she documents local knowledge on the U.S.-Mexico border through her writing, poetry, and the project Herbario Poético, which “explores the unfolding of the identity of the Paso del Norte community from the vegetation of our Chihuahuan Desert.” This book project is a continuation of Sosa’s MFA thesis and explores the symbology of plants, their uses, evolution, and taxonomy to create a “poetic-visual testimony” of the history and culture of the region.

The following Q+A includes excerpts from a virtual interview between Sosa and Michelle E. Carreon, Food Justice Storyteller at La Semilla Food Center, as part of the organization’s inaugural Chihuahuan Desert Cultural Fellowship.

How would you describe your cultural practice?

My cultural practice is mostly literature and writing, but it’s multifaceted. I like to mix different tools and processes. So it ends up being more free. I like to develop projects with a social purpose. For example, I have published a book titled María Cabeza de Empanada, which is a collection of stories from people with disabilities in our region. Right now, I am working on the topic of plants and the way they echo my personal memory and collective memory.

When I was a child, we had to move suddenly. It was an unexpected change and painful. We moved to a small village outside of Chihuahua. It is 100% rural. Back then, nature would envelop me. I would make houses for crickets out of little pieces of wood that I would find. There was a river nearby, and I would walk by the river with my mother and brother. We would see little flowers that were like daisies. I picked one and wrote about that flower. It was a very short poem, but I kept it. Unfortunately, I ended up throwing away the notebook with my writing. So the little flower was gone with the poem. But that was my first writing experience living in a different reality, context, and landscape. Even now, I feel that it determined how I see life and my environment.

What does it mean for you to live and practice in the borderlands?

I really enjoy living in the border region. The whole region has its own rhythm and is permeable. It facilitates a cultural process and allows us to exchange experiences. I’m also a professor. Even if I’m not actively teaching, I’m always thinking about the students and how I can transmit what I know, live, or see.

When I got married, I came to live here with my husband. Having to migrate was a struggle, because my family is very close. You always hear about Juárez being a dangerous place. So I had to see it through my own experience, not just what I had heard. It was hard for me to adapt, but I had to break from the paradigms I had in mind.

I was in a bilingual Master’s program. We had the freedom to use whatever language we wanted, but my English was limited. So I was forced to experiment more, and I discovered my strengths and weaknesses. I had to rely on my memory to find my creative and poetic voice, to find a place that was comfortable for me. I felt quite alone at the university. But this also brought me closer to plants. The geography was something that I could still recognize. It anchored me. It brought me calm and security. This led me to begin this project with the plants. It was an exploration that allowed me to feel and to think.

How is your practice intergenerational?

I consider plants as deposits of memory. It is important to listen to what they have to tell us. I think researching plants is a collective ancestral practice. Maybe right now it’s resting for the present, but it’s something that can be discovered in the future. I really enjoy hearing people’s testimonies and finding a way to pass it on. Learning about the past not so much that we are living in it, but so that we can see its qualities and learn for the present. I’ve been working with the Rarámuri and love hearing what they have to say. All of their cultural knowledge is not written down. It’s passed on orally between generations.

I think that’s another reason why I like working with plants. The past is what teaches us and is part of our identity. It will continue living and will continue to affect us. The past is still right now.