June 6, 2017 – November 11, 2017

University of New Mexico Art Museum, Albuquerque

The Arctic has for so long been defined by distance, both geographically and conceptually. Called the Far North because it is far from some perceived “us,” countless nature writers, documentary filmmakers, and artists render the region visually distant, as an alien white landscape. To represent the tundra as blank and empty casts an entire topographical region as other, along with all its species (including its people), living and extinct. In the midst of the sixth great extinction, such erasures can be understood not just as dismissals but as highly politicized acts of violence carried out in the name of oil, gas, coal, and nuclear waste storage.

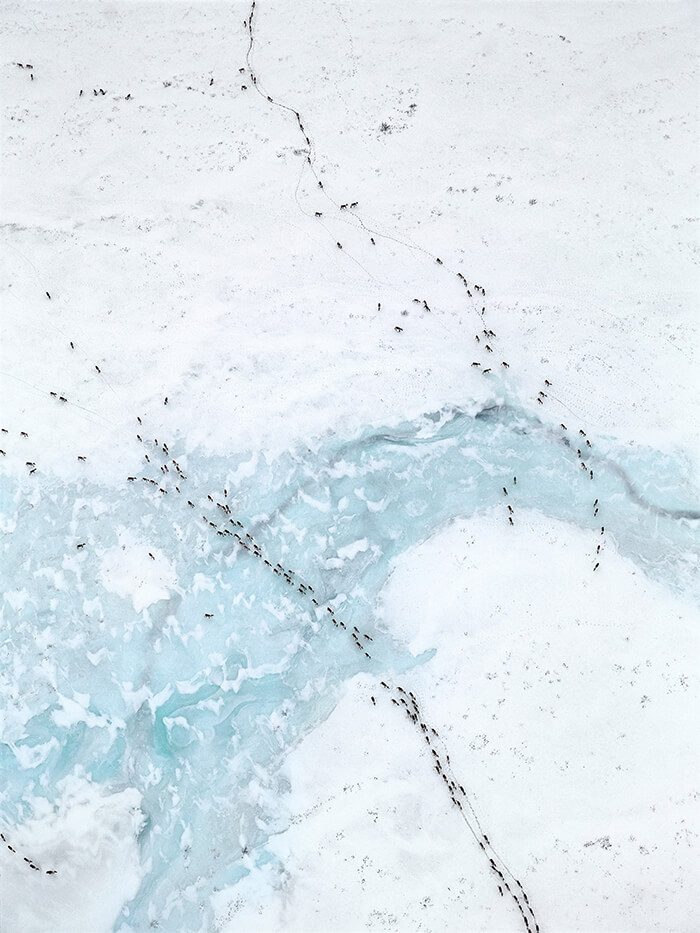

Subhankar Banerjee wants viewers to feel close to the Arctic. To help them do so, he has photographed the landscape’s qualities that seem familiar, rather than exotic: the sunlight on a forested mountain, herds of brown—not white—animals (reindeer, caribou) that at a distance might look like creatures from a more temperate zone. He photographs the interactions between living (and dying) bodies and the land: blood on snow, as carcasses are cleaned after a hunt, and tracks made by animal migrations across grass, rock, and mud. He includes color, like the green-brown of a river filled with geese and goslings in spring. To depictions of the Arctic, the singularly defined winterscape, Banerjee brings color, texture, movement, life, and death. He shows change and its manifestations, especially those wrought by human impacts. His photos and his writing make visible—show the literal tracks—of the mining of coal and the extraction of oil, for decades an otherwise unseen collaboration of US and Russian political magnates that may soon find its fullest realization.

Banerjee was born in India and has degrees in engineering, physics, and computer science. As a writer, photographer, field researcher, and activist, he is extraordinarily prolific. Last year he was named the Lannan Foundation Endowed Chair and Professor of Art & Ecology at the University of New Mexico, and he has published numerous critical and photography books, several of them focused on the Arctic. New Mexico’s land and deserts have also drawn his attention for over a decade. Banerjee is best known in circles of environmental humanists and activists for his concept of “long environmentalism,” included in the title of the show. By “long,” he means a long enough time for societal change to occur, for “collaboration among unlikely allies through the act of sincere listening . . . and a period of time that is long enough to enable what was once considered marginal (like a human community or an idea) to become significant and essential.”(1) Long environmentalism is playing the long game of raising awareness and resisting further damage to already damaged places. People from various groups come together around “the ethics of livability” that figures for both human and nonhuman populations.(2) Our ethics of livability can only come into play if we recognize places (like the Arctic) and species as alive, as life. In his photo After the Listening Session, a group of people “engaged in protecting significant biocultural areas in the Alaskan Arctic from industrial exploitation” gather after hearing from the Secretary of the Interior that the Arctic will be opened up to oil and gas development.(3) This cause has engaged indigenous peoples and environmentalists in a shared fight, and by including the group portrait in Long Environmentalism, Banerjee insists that the Arctic be seen as contemporary, current, and human in a way that photos of the landscape might not suggest.

The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, where Banerjee spent fourteen months, is “considered to be the most biodiverse conservation area in the circumpolar north.”(4) The Arctic can be construed as the untrodden, but this is and always has been false. Still, I fear the effect of the photos unaccompanied by Banerjee’s words, his research. The camera beautifies, flattens, and objectifies, despite his efforts to see the landscape as medium, not object. Beyond the show, Banerjee’s photos have been extracted from their context, to various ends. His photo Polar Bear on Bernard Harbor is the most reproduced photo in the history of photography, after having been part of an exhibition at the Smithsonian that was censored in 2003. Banerjee calls this the “peripatetic life” of the photograph across different media and disciplines. Without his words to accompany them, his photos still offer unexpected depictions of the Arctic, but they are missing the underground components, the depth and the long-term engagement that his research and writing provide. His photos witness, but his writing makes the view three dimensional, tactile, and, most importantly, emotional. One sees the herd of reindeer pausing in the trees with a different heart after reading that Soviet Russia tried to eradicate both the reindeer and their herdspeople, that the current Russian government continues to claim negligible effects of climate change despite massive reindeer die-offs. One sees them as vulnerable.

1-4. Subhankar Banerjee “Long Environmentalism: After the Listening Session.” In Ecocriticism and Indigenous Studies. Edited by Salma Monani and Joni Adamson. New York: Routledge (2017), 62-3.