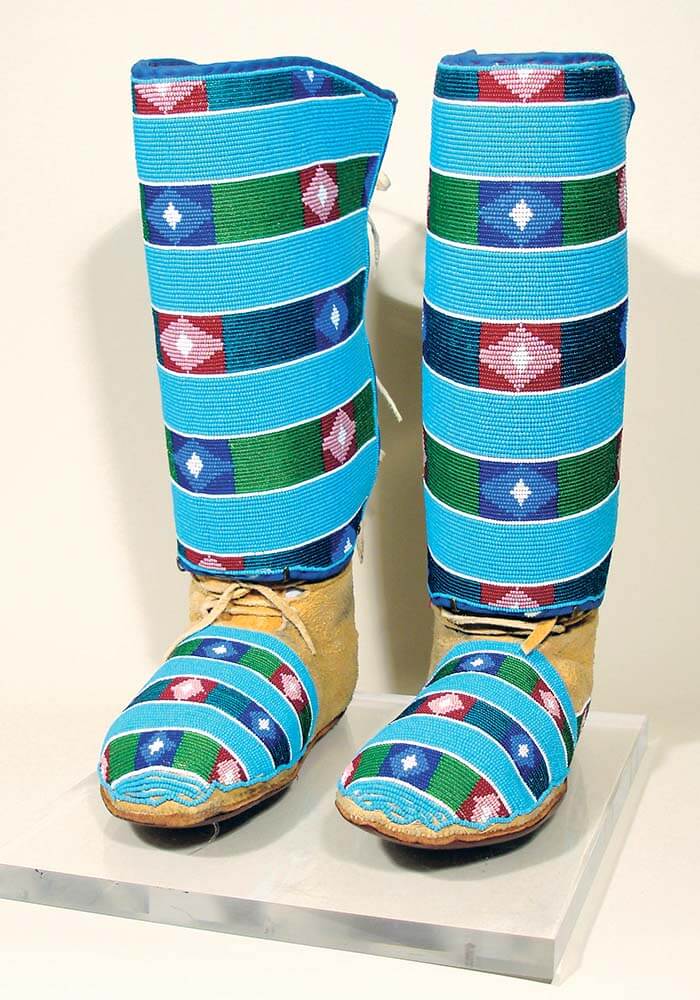

After we finished talking, Nina mentioned that she had to work on a pair of moccasins: she’d started them, then halfway through changed her mind about the design, then started again. Now, only the width needed tweaking. I saw the finished product on her phone: a pair of stacked triangles divided into ochre, red, green, and navy blue geometric shapes stitched across the top of each moccasin. Her work demonstrated the very tenets of Apsáalooke/Crow design: symmetry, white beads for outlines, the liberal use of blue for the background, and the overlay technique. Visually, they were stunning. Culturally, they were stories.

Lively Objects

Beadwork brought Nina Sanders, a member of the Crow Nation and a child of the Whistling Water clan (Bilikóoshe), to the Coe Foundation. Named after the Yale-trained art historian, curator, and collector, Ralph T. Coe, the Foundation holds a vast spectrum of Indigenous cultural production, including examples of beading from several tribes in Native North America as well as objects from Africa and Oceania. Nina, it turns out, came to spend the day looking at a pair of moccasins and matching leggings made by one of her relatives, Yellowtail. Beading ran in her family. “I learned to bead by watching my grandmother, mother, and aunts. I got better by practicing and honed my talent by looking at historic bead work in museums. Beading keeps me grounded; it anchors me to my people when I am away from home,” she said. Coe bought the pair from a trading post when he was on the Crow reservation in Montana in the late 1980s.

Shelves of other objects occupy the first and second floors of the Coe’s Pacheco Street location: a Woodland Cree Wall Pocket, a Haida Totem Pole, Huron Nesting Boxes, a Passamaquoddy Picnic Basket, and even a pair of beaded Converse tennis shoes by local artist Teri Greeves. The collection is in the thousands. A work of art from 2010 might share the same space as an object produced in the early 1800s. It depends on where you look.

The Collection

Coe stands out as one of the few collectors who amassed Indigenous objects continentally and across time. The kinds of art-historical brackets that often separate the supposed historical material from the contemporary, a dilemma that plagues Native art still, held little value to him. These brackets are what executive director of the Coe, Bruce Bernstein, calls a “dichotomy for authenticity.” Here in Santa Fe, galleries continually peddle authenticity, exhausting nineteenth-century images and motifs of Indigenous people. It’s a kind of selective amnesia known to the West that fosters a “fossilized idea” of what actually counts as authentic—something “traditional” and unadulterated from the past. Keeping these outmoded ideas around is like dragging an old beat up suitcase, in Janet Berlo’s words. But once the suitcase goes, it’s clear that Indigenous cultural production exists on a continuum where past, present, and future all intersect.

The Coe Foundation, which is still the new kid on the block in terms of its relatively recent founding (2010), sees its mission as increasing public awareness of Indigenous art and culture worldwide, showcasing the inventiveness of Native makers over time. Based on conversations with Rachel de Wixom, president and CEO of the Coe, a primary concern is making the collection accessible to a larger cross section of Santa Feans and the surrounding area. The collection is open to the public by appointment, and there is no fee for admission. Most of the time, there are no vitrines trapping objects in and keeping handsy visitors from getting too close. “As a curator, you put up a show, you have a certain viewpoint, and then seal it up in those cases, and then nobody has access to that idea. It’s all hermetically sealed. Not having topson the cases is more than hands-on; it means [engaging] those multiple narratives.” Visitors are encouraged to touch objects, turn them over, and have direct contact without “white gloves.” But as Bruce adamantly points out, the endgame is not simply about touching stuff but about having a more meaningful awareness of the cultures that produced such objects. This, he hopes, will differentiate the Coe from other institutions in Santa Fe that operate on a more traditional museum model of collecting and exhibiting. Along these lines, those working at the Coe are not “lone scholars,” producing research for a handful of people, but closer in form to “conductors” in their aspirations to include as many voices as possible.

When I asked Bruce about what he would say to Indigenous people and non-Indigenous people who question the motives of a white collector, his answer was, “Come use the collections and change that,” continuing, “The collector is one reason why people continue to make art. I think that the only way it’s going to change to be more positive is . . . if you get on the inside and make the change.” Yet, on the other side of the coin, “there are people who never make stuff for non-Native people, and that’s really important. What [outsiders] see of the Native world is a small little tidbit. It’s up to the Native world what they want to show.”

The Guest Curator

To Nina, the objects produced by Native peoples are an extension of oral histories. They are stories of another kind that relay something about a maker’s generation, of their process of healing, of “community, love, sex. . . all of that,” she explained over lunch one afternoon. “If you’re a creator, you become a historian in your own way.” Nina, who was an Anne Ray intern at the School for Advanced Research until the end of May, after completing a Bachelor of Science in Anthropology and Indian Studies at the University of Arizona, has been a historian in her own right and advocate for keeping Indigenous communities in contact with their objects. Indeed, stories only live on when they are retold. And when it comes to Indigenous material culture, having access is part of an object’s ability to continue telling its tale.

As part of her advocacy work, Nina participated in the National Museum of the American Indian’s Recovering Voices Program. Her project involved identifying individuals from the Crow Nation in over three hundred historical photographs held in NMAI’s collection. Taken by a German photographer and farm mortgage manager named William Wildscut, those nearly one-hundred-year-old photographs eventually became digitized and accessible through the Smithsonian’s broader online catalogue. Nina’s effort was the first of its kind. More recently, Nina was invited to attend a panel on the future of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), a groundbreaking piece of legislation passed in 1992 mandating the return of Indigenous objects to their respective tribes. Fast forward to the most recent meeting on the topic where Nina discussed the power of objects to mediate new relations with tribes, a lesson learned working in early childhood education with the Crow and Fort McDowell Yavapais.

The Catch 22

Nina has no curatorial experience in the art-historical sense. She’s quick to note that. We even spoke at length about the value of “art for art’s sake.” Her grandmother, at least, doesn’t see its use. To Nina, colonialism, and by extension capitalism, has produced the conditions for an object solely created for the market, especially a Native object, a history she can easily detail. Still, she is one of the Coe’s first guest curators (high school students participated in the Coe’s Young Curators program last Spring with their exhibition The Mirror Effect: Reflections Upon our Realities) and their first Native curator, presenting the first exhibition of contemporary works on paper made by emerging and established Native artists. Until now, exhibitions have mostly featured objects from Coe’s shelves, though A View from Here: Northwest Coast Native Arts, which culled material from the collection of Richard and Joan Chodosh, opened last August. This time, Nina handpicked twenty-two artworks from the collection of a retired high school English teacher from Yonkers. Edd Guarino, the self-described “Herb Vogel of Native Art,” has collected works on paper since the ’90s, with a focus on Native North American and Inuit art. Edd is not wealthy—he typically buys on layaway—and often collects the work of emerging artists. While his collecting began in pottery, he now almost exclusively collects works on paper, which number between three and five hundred, mostly so that he can collect and store more in his Yonkers apartment. When I spoke to him over the phone, he was excited that the Coe was yet another institution that was exhibiting his collection. The Brooklyn Museum, MoCNA, and NMAI count as others.

Collaborative relationships with Bruce and the Coe’s assistant curator, Bess Murphy—who has coordinated with artists, functioned as a registrar of sorts, and developed programming—grew as the show took form. Each, it seemed, drew from the others’ knowledge banks. Nina also got to know artists, having them open up about the kinds of world views that shaped their work: “we broke bread, sipped lattes, sat on park benches, and watched tourists together,” she mentioned. In her words, the eighteen artists in Catch 22 are not only “telling a story of their generation but expressing the conflict of art for art’s sake.” The exhibition, aptly titled Catch 22: Paradox on Paper, embodies this and other contradictions.

One evening I was going through the photos on my phone and stopped on a photo of my mother’s pickup truck with several bales of alfalfa in the back. I was staring at the photo, and the 22 on her license plate caught my eye. For one reason or another the 22 became Catch 22, a paradox, contradiction. Perhaps it was the muse—maybe it was my lack of sleep—but it stuck and the show began to take shape.

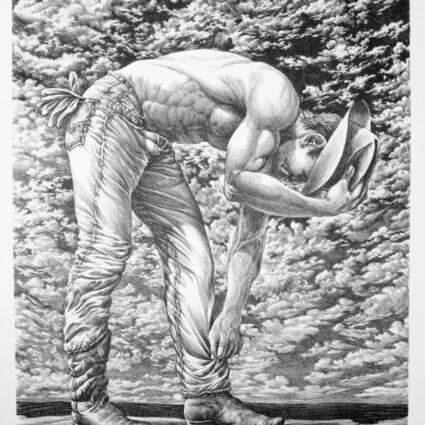

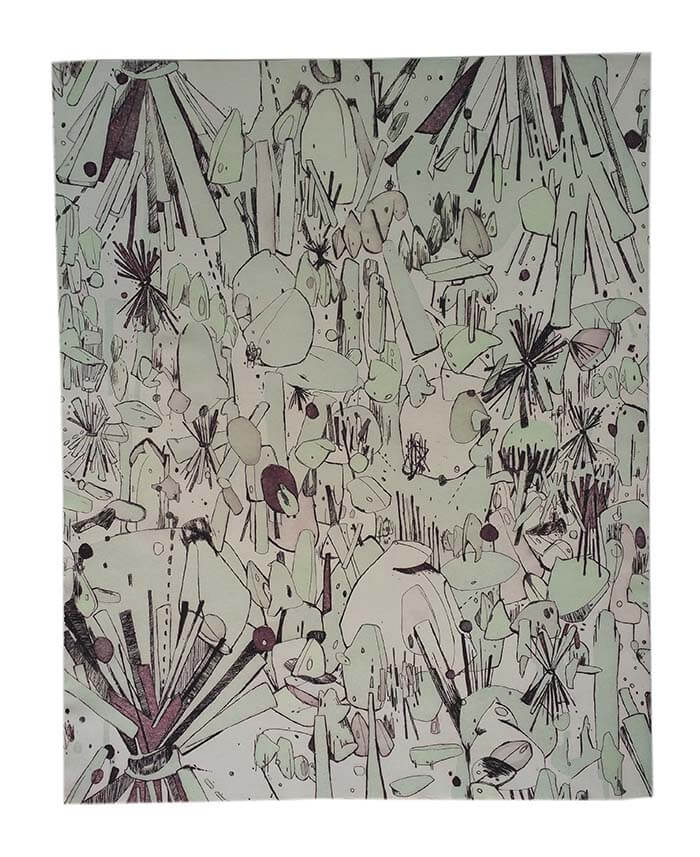

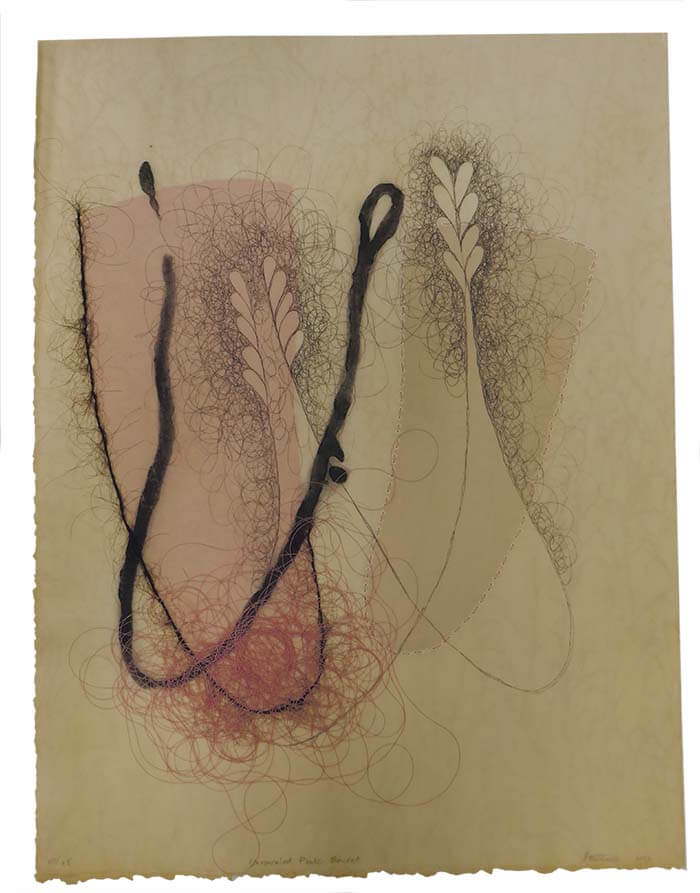

The individual artworks share the substrata of paper in common. Each, however, is remarkably diverse. I was able to see this firsthand when Bess invited me to come into the Coe as she, along with Rachel, unpacked the works after they’d been shipped from Yonkers. Some are delicate, like Sonya Kelliher-Combs’s Unraveled Pink Secret, an amoeba-like form crafted from pale pink thread, hair, and wax. If the artwork did reveal its secret, the answer would come as a whisper, so intimate is the work. Others, such as Unrestrainable by Shan Goshorn, could fit in one hand. A small woven basket, Unrestrainable suggests a history that even the vessel cannot contain: each woven strip of paper has the name of a child who was forced to attend the first boarding school for Native peoples, Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania (1879-1918), as well as verses from the Bible translated into Cherokee. Justus Benally’s Manuelito, a printed image of the renowned Navajo chief, defaces a 3.5 x 5 inch U.S. postage label. It is, in Benally’s words, an example of “graffiti sticker bombing.” In A La Machina!,” Eliza Naranjo Morse takes the norteño statement of awe and frustration as a title for an image that conjures a tiny ecosystem of creatures as if glimpsed through a fantastical microscope. The outward innocence belies the artist’s attempts at making sense of colonialism, gender, and the commodification of art.

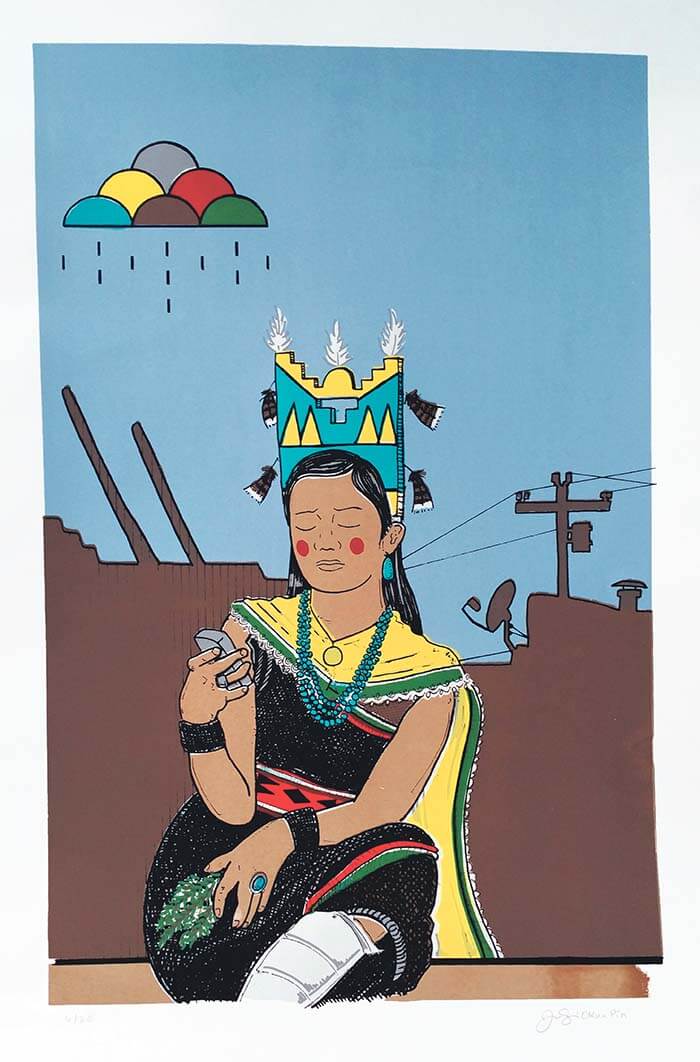

A corn maiden, replete with her tablita headdress, pauses from dancing to check her phone in Jason Garcia’s serigraph, Corn Maiden. She haphazardly scrolls through social media, unimpressed. Behind her, the silhouette of a phone line and a satellite dish can be seen against a blue sky. Sarah Sense’s Elizabeth as Cleopatra culls from a scene in the 1963 Hollywood blockbuster, Cleopatra, starring Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton. The warp and weft of the paper tapestry bring together Elizabeth-as-Cleopatra’s eyeliner-laden gaze with the golden Chitimacha patterns that the artist has used for over ten years. When Sense described her role in making Elizabeth as Cleopatra, a commission from Edd that took some time to negotiate, she got at the heart of artistic self-determination: “I did go back and forth about including myself in this piece, but I think that as the maker I was in it without the literal imagery.” Hers, like others, is the art of revealing and withholding, even down to the level of depicting, metaphorically or literally, oneself. In yet another example, a female form lies supine, her nude body draped over a V8 engine. The linework is graphic and striking: black marker and pen against a crisp white page. Not quite cyborg, yet otherworldly nonetheless, Rose Simpson’s ethereal figure floats in space, ecstasy meeting repose. It’s simply titled: V8 Engine. These are only a handful of Catch 22’s checklist. And when I saw them all laid out on a table at the Coe, it was clear that once on the walls, the result would enthrall, begging slow, close explorations of each work’s internal cosmos.

Of course, to have such an experience in a setting that is, for all intents and purposes, museum-like brings to light the dilemma of “gatekeeping” for Native makers, as another of Catch 22’s artists Linley Logan writes:

I struggle with the idea that there are gatekeepers who believe they are allowed to determine what Contemporary Native art is. However, as I’ve become more experienced and confident in my work, I’ve learned to transcend these ideologies by creating on my own terms. I can say now that by taking this position I am sure of what I make, what it means, and who it is for.

Many of the artists’ statements reflect this and other tensions, like what it means to create traditional art. For Kelliher-Combs, the question is not about abandoning the idea of tradition altogether, but updating it: “Why should we have to distinguish the idea of tradition when we are building traditions every day? We change and adapt and and learn from our experiences, then incorporate that into what we make; that is a bigger tradition.”

The exhibition, in a sense, is about processing—that is, about making meaning from contradiction. And in the multifaceted role of “actors, contributors, players, and creators in history, not just victims,” as Nina put it, all the artists in the show are in some way dialoguing with complex and sometimes unresolvable personal and collective histories.

Looking Forward

As for the Coe, there are plans for a new building in the Siler Road district, an experimental space where all the collection’s objects will be accessible all the time. This is part of turning the museum world inside out, “like a paper bag,” in Bruce’s words. That said, when I think about the future of any institution, I think about the objects, yes, but also about the institution’s ability to more faithfully reflect all of its communities and on all levels. Part of decolonizing our institutions means making Indigeneity a primary point of departure for their envisioning and actualization and getting away from the histories of “gatekeeping” that Logan pointed out. This is a goal for the Coe, I suspect, and a provocation to other institutions, too, especially in Santa Fe, where demographics are rapidly changing and where bringing in different voices isn’t just a matter of strategy but of self-determination.

As for Nina, she plans on a number of public speaking engagements and, in the not-so-distant future, building a museum on the Crow reservation.

“Self-determination,” in her words, is “not a choice but a way of life”:

[My mentors] have prepared me for leadership and service by teaching me to use Crow knowledge systems to navigate life. I now understand that Indigenous ways of knowing are not inferior to colonial convictions. . . . I’ve experienced traumatic violence, poverty, parents with addiction, and racism. However, I managed to transcend those experiences by focusing on the foundational beliefs and practices of the Crow people. . . . I come from a line of bionic Crow women who tanned their own hides, moved entire camps across vast stretches of land, rode horses into battle, gave birth to children in tipis in below zero temperatures, survived warfare and disease, made medicine, obtained college degrees, and still maintained their language and culture.