Leon Polk Smith: Hiding in Plain Sight at the Heard Museum focuses on focuses on Smith’s early works, hard-edge paintings, shaped canvases, and his deep connection to Native culture.

Leon Polk Smith stuck to a style he helped invent. The Oklahoma-born artist is cited as a founder of Hard-edged painting, a form of Minimalism often associated with geometric abstraction that features sweeping color swaths arranged in clean-lined and monochromatic patterns.

It’s possible that he flew a bit under the radar, especially compared to younger contemporaries (Ellsworth Kelly, Jack Youngerman) that art scholars say were influenced by Smith, because he didn’t bow to en vogue styles throughout his six-decade art career. Smith passed away in 1996 at the age of ninety-one, a year after a retrospective exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum brought the artist additional hail.

“What I found really interesting about him is that he did not deviate,” says Joe Baker in a phone interview with Southwest Contemporary. Baker, along with Diana Pardue, co-curated Leon Polk Smith: Hiding in Plain Sight, a new and original exhibition currently on display at the Heard Museum. “He wasn’t prone to the whims of the art world and the current fashionable moments. He stayed very true to his vision.”

The exhibition at the relished Phoenix institution for traditional and contemporary Indigenous art focuses on Smith’s early works, hard-edge paintings, shaped canvases, and pieces from the Constellation series. An added layer to Hiding in Plain Sight is a survey of Native American functional and cultural items, such as a parfleche and a women’s wearing blanket, that influenced Smith’s bold colors and irregular geometric designs.

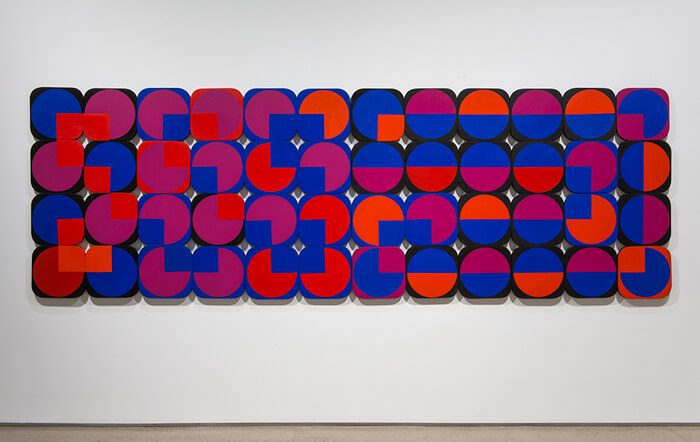

Unlike Piet Mondrian, who was one of Smith’s favorite artists, the Oklahoman simplified his color blocks by arranging just a handful of colors versus dozens or hundreds abutting one another. Inca (1970), an approximately twelve-foot-long rectangular acrylic-on-canvas of purples, reds, blues, and Ms. Pac-Man shapes, is an inventoried yet elaborate tone study that recalls an intensely hued sunset on the Plains. Constellation Happy Day (1971) prunes bold applications of four colors in three standalone yet interconnected circular canvases in a gestural theme of repetition.

Though Smith spent a majority of the latter half of his life on the east coast, his art and spirit remained mingled with Oklahoma. The Heard exhibition reserves an entire room for Territorial-era works that Smith, who identified as Cherokee (there’s no evidence of official tribal enrollment for him or his family), may have encountered as a youth living in the rural Midwest in the early-20th century.

It’s evident by Smith’s artworks that he was deeply connected to Native culture. The display of the Territorial pieces brings that relationship into sharper focus. A lattice cradle and a parfleche by an unknown Kiwa artist, a shield by an unidentified Comanche artist, and leggings by an Osage artist are paired with tiny facsimiles of Smith’s works from the show, illustrating Smith’s emulation and mimicking of Indigenous art and cultural artifacts in the form of contemporary geometry and surface design.

For instance, a detail of Inca is shown next to a women’s wearing blanket by an unidentified Prairie artist from circa 1900. The cultural work of wool, glass beads, silk, ribbon, cotton thread, and a mesmerizing stars-and-shapes configuration are similar to the modular construction of Smith’s dreamy sunset-like scape.

Perhaps the only aspect of the show that begs for more material is a TV monitor that shows a handful of pages from three journals that co-curator Baker said he recently discovered at Smith’s home studio in Shoreham, New York. The displayed pages illustrate Smith’s type-A attention to note-taking that includes a travel-type diary of his works, down to the minute detail of the exact date one of his paintings traveled from a storage unit to a gallery.

Otherwise, Hiding in Plain Sight succeeds at presenting Leon Polk Smith as an American artist who couldn’t have become a unique voice of modernism without Indigenous culture—and in a way that honors Native peoples instead of exploiting or appropriating them.