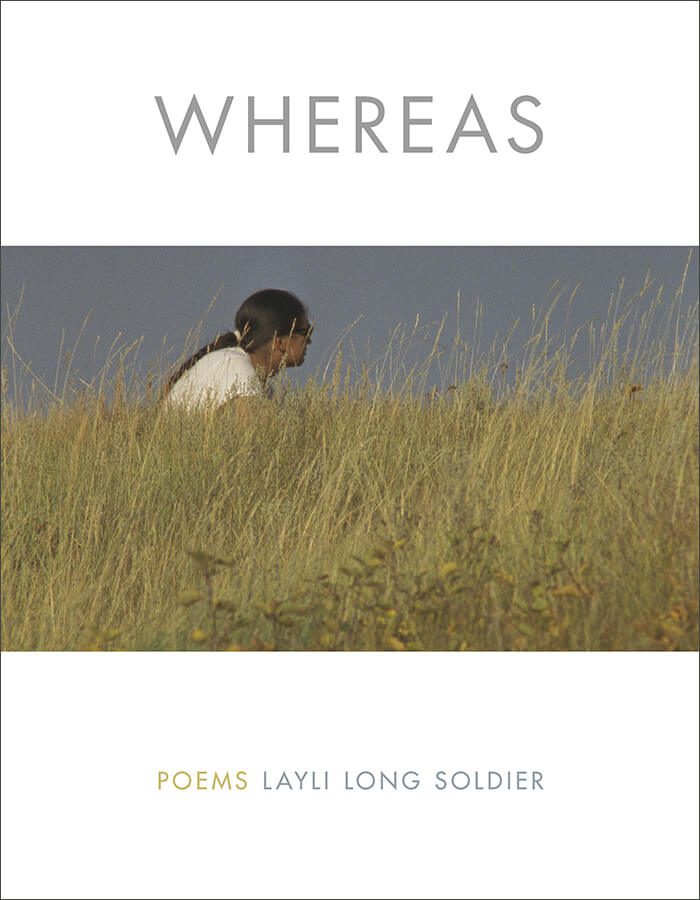

WHEREAS by Layli Long Soldier

Graywolf Press, 2017

At the heart of Layli Long Soldier’s WHEREAS lie two apologies. One comes from the poet’s father for his drinking and his absence during her childhood. This apology, spoken through tears at a breakfast table when the poet is an adult, sinks right in. Father and daughter find a way past their past. Another apology, made by the US government, provides the impetus for the book, its title, its insistent wrestling with words and their effects. The Congressional Resolution of Apology to Native Americans was signed by Barack Obama in 2009, but “no tribal leaders or official representatives were invited to witness and receive the Apology on behalf of tribal nations. President Obama never read the Apology aloud, publicly,” Long Soldier writes. The resolution begins with a statement of acknowledgment—”To acknowledge a long history of official depredations and ill-conceived policies by the Federal Government regarding Indian tribes and offer an apology to all Native Peoples on behalf of the United States”—and proceeds with a series of statements beginning with the word “Whereas.”

Long Soldier uses the word “whereas” as a hinge throughout Part II of her collection and quotes inconceivable statements from the Resolution that hide behind that qualifier, such as, “whereas the arrival of Europeans in North America opened a new chapter in the history of Native Peoples.” One poem that uses this line recalls how the poet told her daughter not to laugh off her pain when she falls down. Instead, she advises, “If you’re hurting, cry.” But the poet realizes that she herself can do nothing but laugh in the face of the words “opened a new chapter in the history of Native Peoples” in reference to a legacy of human atrocity, of “gratuitous slaughter.” Her daughter is following her mother’s lead, letting the hurt roll off her, but in this collection, the poet wants to find a way to voice hurt in the present moment.

WHEREAS is so dense, so charged, that by the end it’s nearly possible to forget that Long Soldier has included poems about her harrowing miscarriage, about the everyday experience of poverty, about her elated longing for her husband. One image unlikely to fade from the reader’s mind begins the collection:

Now

make room in the mouth

for grassesgrassesgrasses

It is not until some fifty pages later that the full meaning of these lines, and the other mentions of grass throughout Part I, become clear. During the Sioux uprising, the poem “38” explains in strident, complete, punctuated sentences, a trader said that if the Dakota people were starving, “let them eat grass.” When his body was found, “his mouth was stuffed with grass.” To fill the mouth with grass rather than words, to suggest that grass might suffice after the government has taken from the Dakota people their right to hunt, their land, their chance at survival—these are the uses of language that Long Soldier draws the reader to fixate on, to register and remember. Throughout, she adamantly attunes to all the ways in which language can be used to conceal violent actions. In the Congressional Resolution, genocide is rephrased as “conflict.”

Like the resolution, Long Soldier’s collection ends with a disclaimer. “DISCLAIMER.—Nothing in this book (1) authorizes or supports any claim against Layli Long Soldier by the United States; or (2) serves as a settlement of any claim against Layli Long Soldier by the United States, here in / the grassesgrassesgrasses.” By tracking and responding to the precise language of the Resolution, Long Soldier makes it clear how language masks and controls the narrative, and by using that same language, she subverts some of its power (not unlike the 2016 collection LOOK by Solmaz Sharif, which draws on the lexicon of the US Defense Department’s Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms). In place of grass, in place of official statements made of euphemisms and revisions, Long Soldier offers her father’s honest apology, her reminder to her daughter to express what she feels rather than conceal it, her tears at reading a story about the budget cuts to Indian Health Services. Despite their endless questioning and defining of words, the poems in WHEREAS also insist that language itself is adequate to address, to repair, to heal. That it can offer “curative voicing,” if we choose our words and gestures carefully.