Laughter and Resilience: Humor in Native American Art

November 10, 2019–October 4, 2020

Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian, Santa Fe

Located on the southwestern end of Museum Hill, the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian is a unique haven for extraordinary creations by Native American artists in every conceivable material and from nearly every period of New Mexico’s history. The current exhibition, Laughter and Resilience: Humor in Native American Art is its centerpiece for the next year. From the museum’s entrance viewers are led from one small enclosure to another, following a spiral-shaped arrangement grouped by themes until they reach a central space wherein lies a subtle but potent surprise. Each room is populated by masterworks from the hands and imaginations of such notable artists as Sheila Antonio, Shirley Benn, Cara Romero, Jason Garcia, Diego Romero, Ricardo Caté, David Bradley, and Bob Haozous.

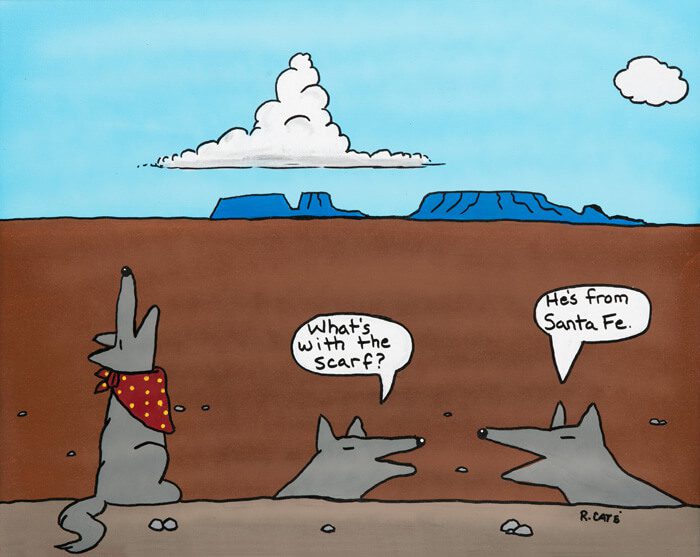

The initial images celebrate the antics of Coyote, perhaps the most important trickster figure of many Southwestern Native tribes. This is followed by a display of mainstream characters and cartoons which have been incorporated into contemporary Native art, employing traditional forms such as woven textiles, kachina dolls, pottery, and bolo ties. Unexpectedly, embedded in these crafts are figures like Tweety Bird and Mickey and Minnie Mouse, together with the Pizza Hut logo. Seeing these pieces of pop culture memorialized in such ways is a real mind bender—but also a source of delight and a cause for laughter.

This section is followed by another dedicated to whimsy and innovation by Native artists. The section is equally full of surprises. For example, what first appears to be a traditional Navajo necklace laden with silver, turquoise, jet, shell, and coral upon closer examination turns out to be an ingenious pairing off on each of its two strands of marine imagery, including seahorses, jellyfish, dolphins, sharks, and fish. In its iconoclastic bent, this work by Valerie Comosona (Zuni) is supremely refreshing.

Nearing the center of the spiral, the works become progressively more steeped in social and political commentary. Were they not cloaked in humor, they might be deemed to be too controversial or even confrontational. A case in point is Tools of the Trade by Tom Farris (Otoe-Missouria Cherokee), a slot machine labeled “Manifest Destiny,” a mechanism that has paid off handsomely, if the overflowing heaps of money at its base are any indication.

It is as if, at the end of the show, curator Denise Neil meant to inform us that, although lighthearted at the beginning, this compelling body of work is really about the very serious issues of resistance, struggle, and self-determination, rendered in ways that humanize and enlighten, rather than alienate or antagonize.

The real surprise, however, lies at the very center of the exhibition. Resting on the ground is a small, black, manufactured child’s car. Its seats are upholstered with a brightly colored Navajo blanket, and its hood ornament is of a Plains Indian warrior, replete with war bonnet. On the driver’s side, artist Tom Farris stamped the chassis with a blood-red handprint. The words “War Pony” leap out at the viewer on the passenger side. It is as if, at the end of the show, curator Denise Neil meant to inform us that, although lighthearted at the beginning, this compelling body of work is really about the very serious issues of resistance, struggle, and self-determination, rendered in ways that humanize and enlighten, rather than alienate or antagonize.

The late Tewa storyteller Esther Martinez once recounted how trickster Coyote was outsmarted by Jack Rabbit, whom he had cornered with his back up against a cliff wall. Rather than pleading for his life, Jack Rabbit chose to assume a role of strength and authority. He let Coyote know that he had better not eat him because he was doing something important by shoring up the wall against imminent collapse. With this argument, Jack Rabbit convinced Coyote that they should trade places, while he went off to look for more help. Because of Coyote’s fear, he dares not leave his post until Jack Rabbit’s return.

The story, though funny, is indicative of the huge discrepancy in might, opportunity, and wealth (to say nothing of worldview) that exists between the dominant culture and the surviving Native American tribes—the subject of much of the artwork. It is also emblematic of the sensitive and witty approach to this lopsided equation that this cadre of Native American artists has chosen to take. Like Jack Rabbit who confronted Coyote with neither fear nor resistance, the thirty-five featured artists have opted to use the disarming power of humor, parody, and satire to counter, transcend, and transform the oppression they have suffered.