Artist Jon Revett makes a pilgrimage to see his mentor Larry Bell’s career retrospective in Phoenix, and view what the Light and Space master calls his last cube in Taos.

“Hey Monet,” began my emails to Larry Bell in the early aughts because of his association with the Light and Space movement. These artists used a Minimalist vernacular to accentuate the perceptual responses to their works. Bell achieved these results by playing with ephemeral effects of light on coated glass, reminding me of Monet’s serial paintings of water, haystacks, and cathedral façades—earning him the moniker “the Monet of Minimalism.” Over the years, he would occasionally send me pearls of art wisdom, which have shaped my own practice. This includes the best piece of career advice I’ve ever gotten, and one I continue to tell my own students: “Do not quit.” As an homage to this Minimalist mentorship, I took a road trip from my home in Canyon, Texas, to see his recent exhibition Improvisations at the Phoenix Museum of Art (which concluded on January 19).

I begin my journey on Interstate 40 heading west from Amarillo. This portion of I-40 was originally Route 66, a road woven into our cultural fabric. Like Route 66, Larry Bell began in Chicago, born there in 1939. Then his family moved to Los Angeles, the terminus of the Mother Road. He grew up there, eventually enrolling in Chouinard (now CalArts) and fell under the spell of Abstract Expressionism, but he abandoned school and painting. Later in life, Bell was diagnosed with degenerative nerve damage meaning he had lost forty percent of his hearing. A lifetime of undiagnosed partial deafness had resulted in poor academic performance and “a lot of time [spent] sitting in corners” as a child.

At Santa Rosa, I depart south from I-40 to meet up with Highway 60. Within a few miles on Route 66’s scenic little brother, the landscape opens to the blinding white of Laguna del Perro, the salty remnants of a Pleistocene lake. Its shine distorts the horizon, causing the Sangre de Cristo mountains to float over the northern horizon, revealing that New Mexico, where Larry Bell lives now, is the real land of light and space. Its unique atmospheric conditions fill the sky with riotous colors of dusk and dawn and make ridgelines hover. These visual effects are created by variations of vapor, which is also a central component to Bell’s work.

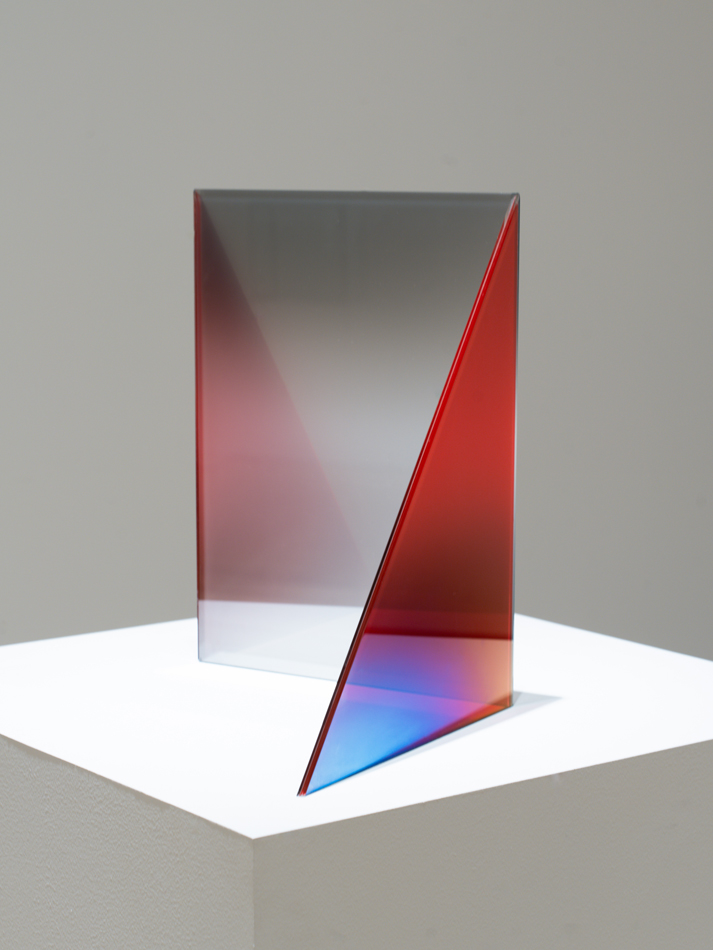

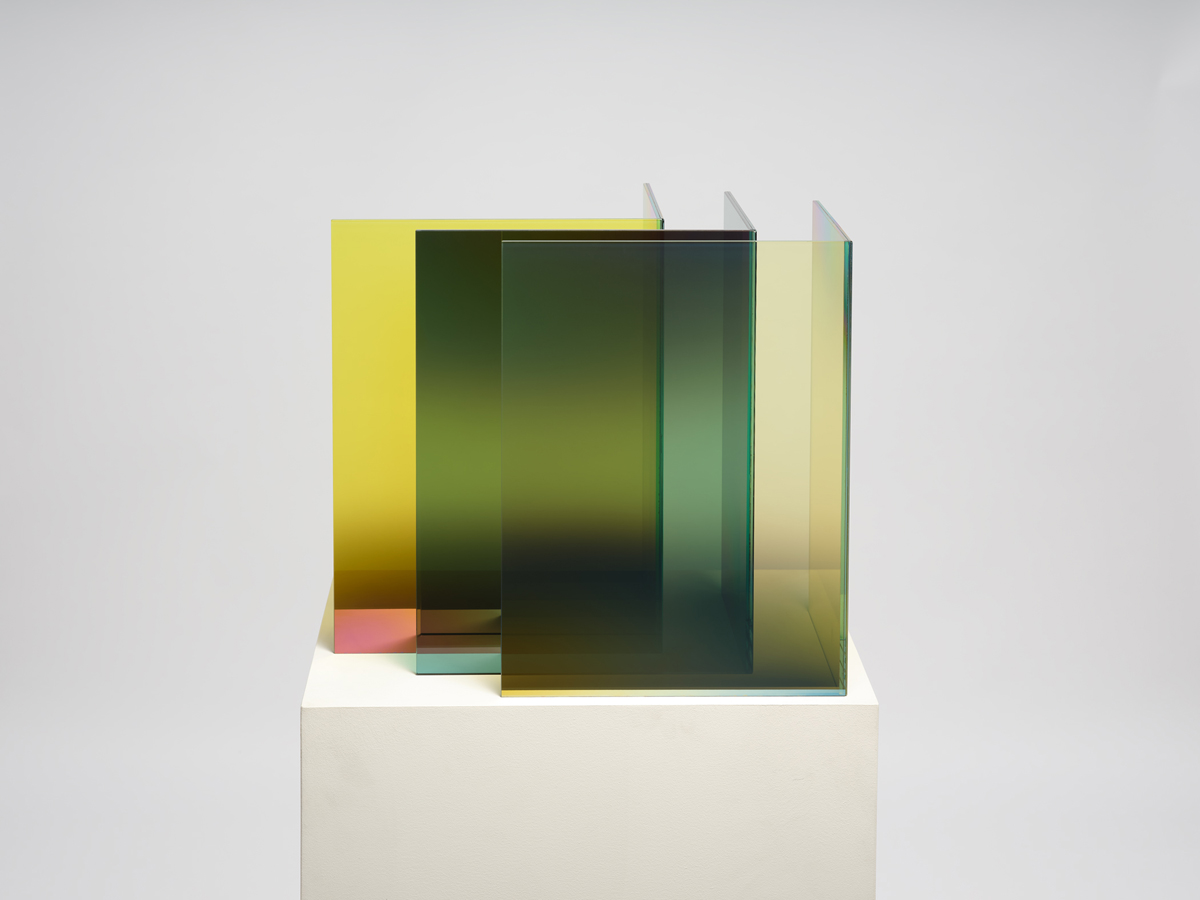

Early in his career, Bell began a systematic investigation of the effects of vacuum deposition of vaporized materials on a variety of surfaces. His art is the result of this array, and as Highway 60 takes me across the Rio Grande, I find another: the Very Large Array, a radio observatory composed of a twenty-eight enormous radar dishes twenty miles west. This facility choreographs a series of dish positions to observe the wonders of the universe with radio waves. Its configurations serve as a control to get a better look at the unknown, not unlike Bell’s use of vapor-coated cubes, which give us the ability to see on, in, and through them. This motif has continued throughout his career, though his grounds have expanded from sheet glass to paper, mylar, canvas and anything else he can fit into his vacuum chamber.

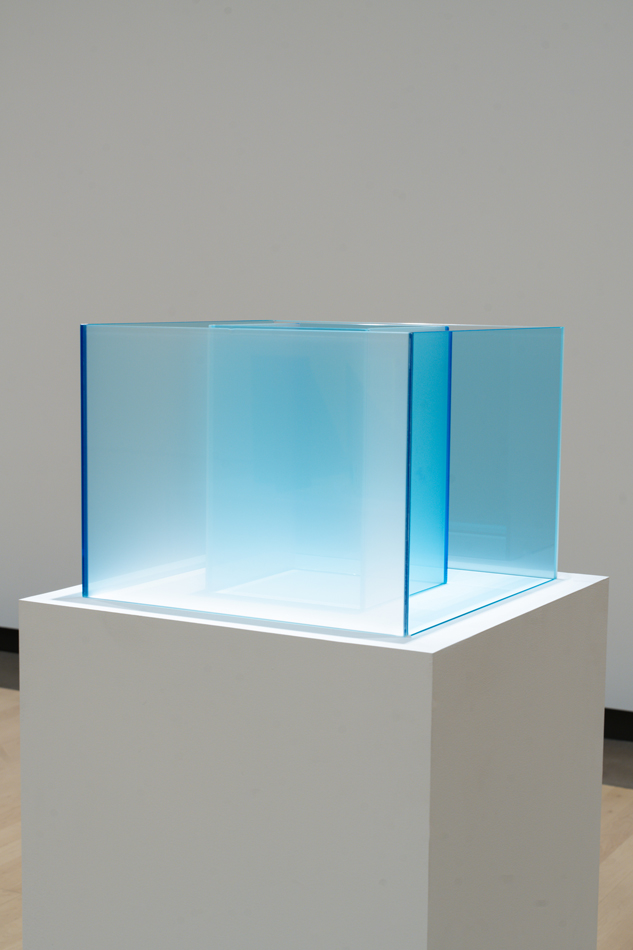

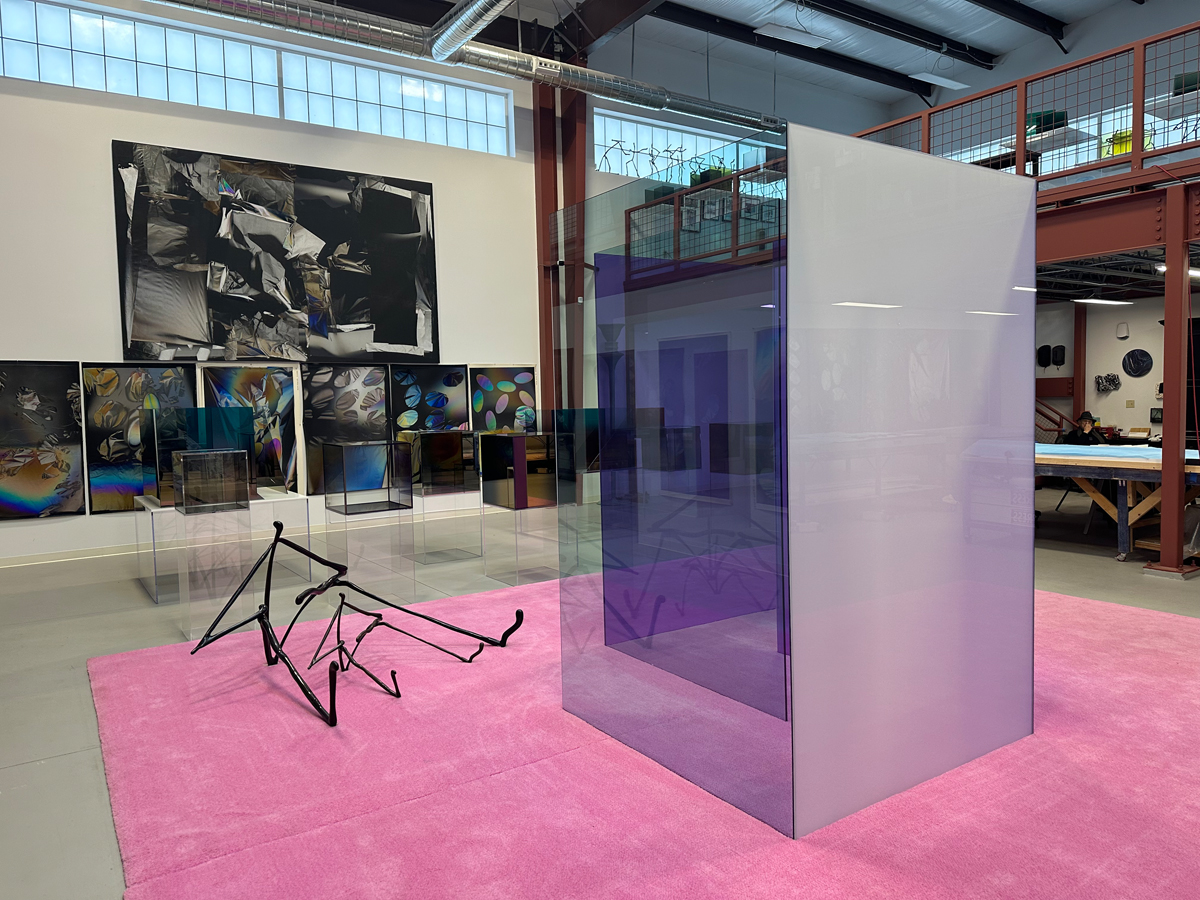

I find myself in Taos at Bell’s new studio expansion, where he shows me what he thinks is the last cube he will make.

Farther west, Highway 60 descends into the Salt River Canyon revealing one of the most dramatic landscapes on the drive. The canyon becomes an enormous crack in the mountains of eastern Arizona. Another, smaller crack led Bell to his interest in glass. In an attempt at framing an early work, the glass fractured, revealing a triumvirate of effects that became fundamental for Bell. Glass reflects, transmits, and absorbs light, inspiring him to investigate the reflective surfaces of mirrors, often created by vacuum deposition.

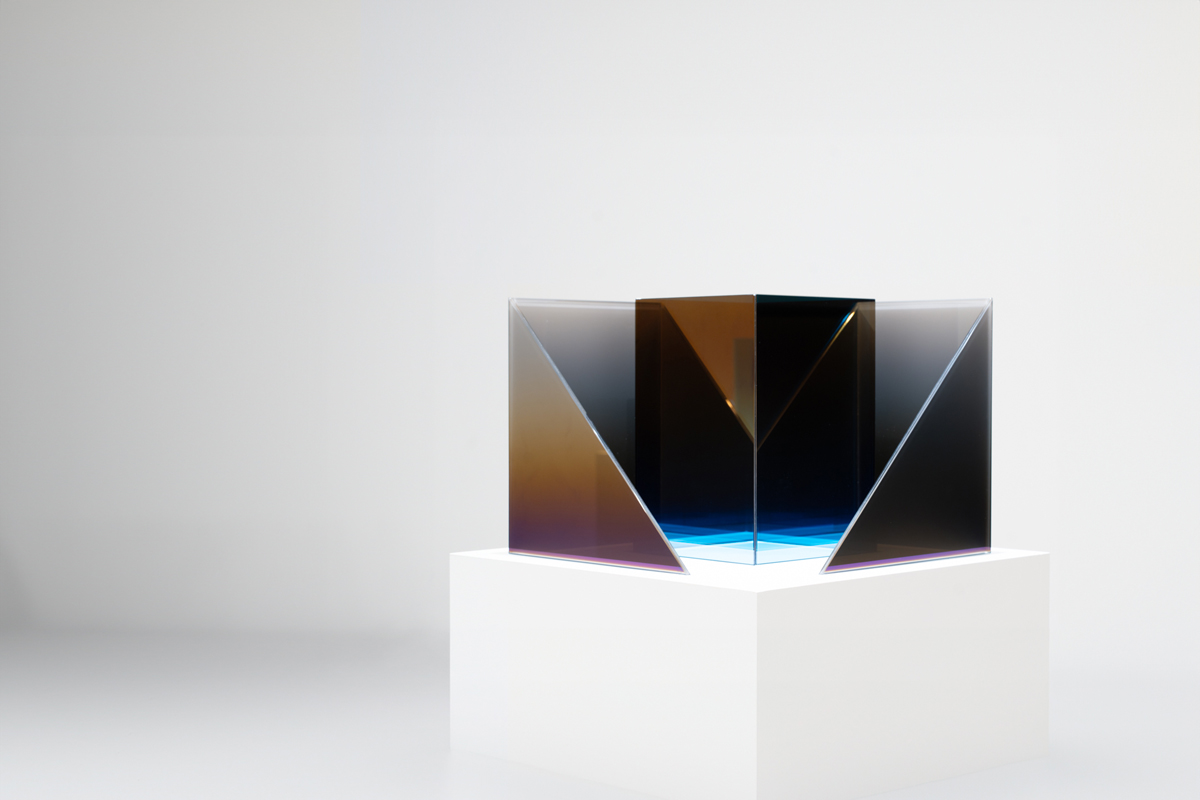

After climbing out of the Salt River Canyon, right angles coalesce from the wilderness indicating human existence. Terraced strip mines foreshadow the industrial architecture of mining towns, which evolve into the fully formed urbanization of Phoenix. This world is one of cubes and its box-like variants. Cubes also frame Improvisations, Bell’s career retrospective at Phoenix Art Museum, which spans more than fifty years of output. In a corner of the first room, a small glass cube from 1969 is one of his initial investigations. Accompanying this ur-cube are more examples of expanded cubes, both in color and form. Another room holds The Cat (1981), a large glass cube dissected and reconfigured to site-specificity. His two-dimensional work is on display in the next room. The surfaces of his fragments, vapor drawings, and collages shift between metallic and matte, exposing the colored gradients.

Rachel Zebro, the exhibition’s curator, did an excellent job comparing and contrasting the expanse of Bell’s practice. She completes the framing of the show with 2024’s Triptych in Glass. These three large, multi-colored cubes remind me of shimmering 3D versions of Josef Albers paintings. The cube is to Bell what the square was to Albers: a matrix for experimentation, but Bell moved past oil paint and made industrial process his medium. Artists have historically integrated new technologies and scientific discoveries into their practice. Had I dived any deeper into the artistic use of glass and the atmospheric effects of vapor, this essay would become an art history lecture, and if we are in a new Renaissance, Larry Bell is one of the Great Masters.

Two weeks later, I find myself in Taos at Bell’s new studio expansion, where he shows me what he thinks is the last cube he will make. Like the drive to Phoenix, it has been a long road for Larry Bell. He has spent the last fifty years playing with form and materiality, and in our talk, he exposes the key ingredient to his process—“It’s all improvisation”—revealing the impetus for the exhibition title. He made his own way across the plains and peaks of artistic process and presentation, and his triumph is his continual return to the cube, the perfect confluence of corners. Bell has conquered the place he was unfairly sent in his youth by making his corners beautiful.