Bucking the solemn tone of much performance art, Right on Time collective’s sweaty, cyclical extravaganzas herald a roaring late-2020s vibe.

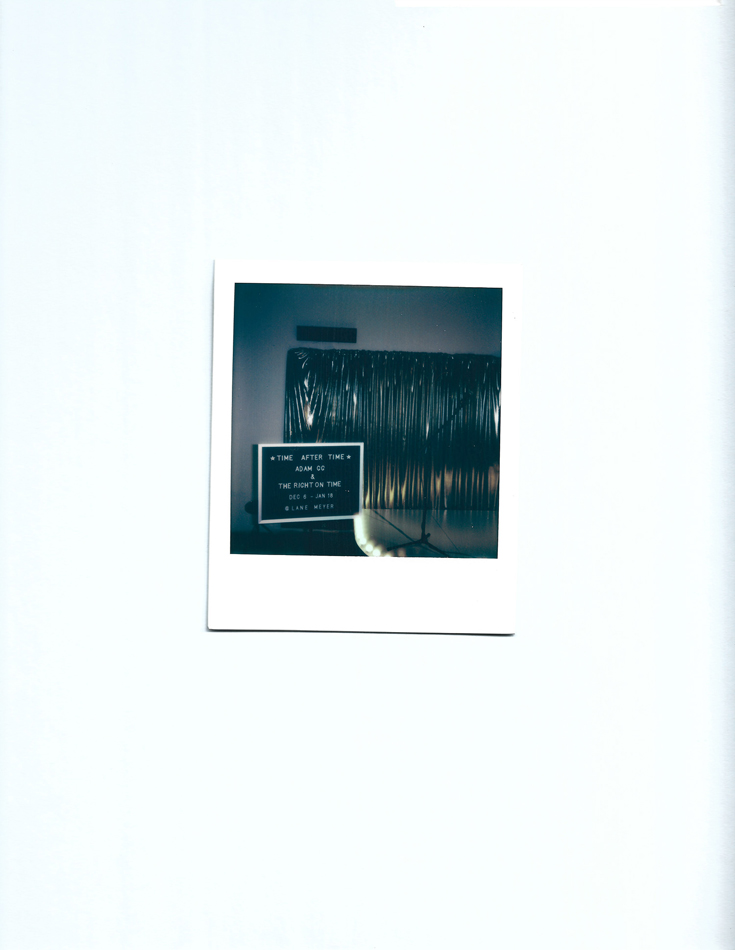

Pon Pon Bar is stuffed to the gills. I’m already late to an exhibition opening presented by Adam Geluda Gildar and the Right on Time collective—an irony not lost on me—and I squeeze through the crowd towards Lane Meyer Projects with a nervous pang. I’ve come to see the first of eight multi-hour karaoke performances titled Time After Time, and frankly, I don’t know what to expect even though I read the exhibition’s press release.

Time After Time’s premise is simple, yet exacting: each night, one karaoke song is performed live on loop for four hours and thirty-three minutes, beginning at 4:33 pm. Every presentation is “anchored” by Geluda Gildar or one of the Right on Time—Ben Coleman, April Frankenstein, Elle Hong, Matt Shaw, Laura Shill, Derrick Velasquez, or Joshua Ware—who have chosen songs about time, committed to the bulk of their night’s efforts, and lent their own niche to the collective. But anyone may sing, provided that the song is kept alive for the duration.

With just one number on each setlist, the potential for boredom or hysteria is high. “On paper, this (exhibition) is going to drive people crazy,” says LMP senior director and curator Brooke Tomiello, acknowledging that folks at Pon Pon had doubts because of their proximity to the LMP space. “Alienating paying customers was a very real possibility,” Geluda Gildar also admits. “Unlike (in) a traditional gallery, transgressing social norms can be a price to pay for a bar,” he says, thanking Tomiello for her advocacy and Pon Pon owner Eric Corrigan for ultimately supporting the experimental work.

Karaoke’s generative potency is about ‘how much you’ve committed to yourself in front of others.’

I reach LMP’s doorway beyond Pon Pon’s bartop in what feels like slow motion, parting the hefty velvet curtain as though seeking an audience with the Wizard of Oz. I’m knocked back by a shock of noise and a blast of hot air, the room crowded with flushed and glowing bodies gazing, wiggling, chatting, drinking, cavorting, swaying, listening, singing, laughing, sweating. It’s hot in here, I think to myself. And this is an excellent use of free will.

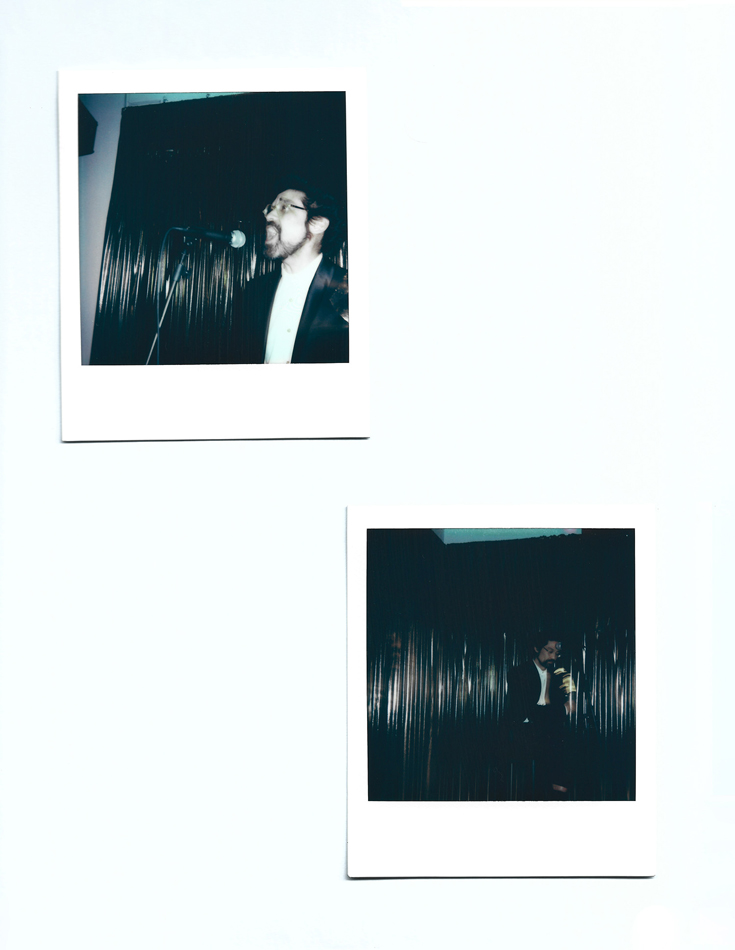

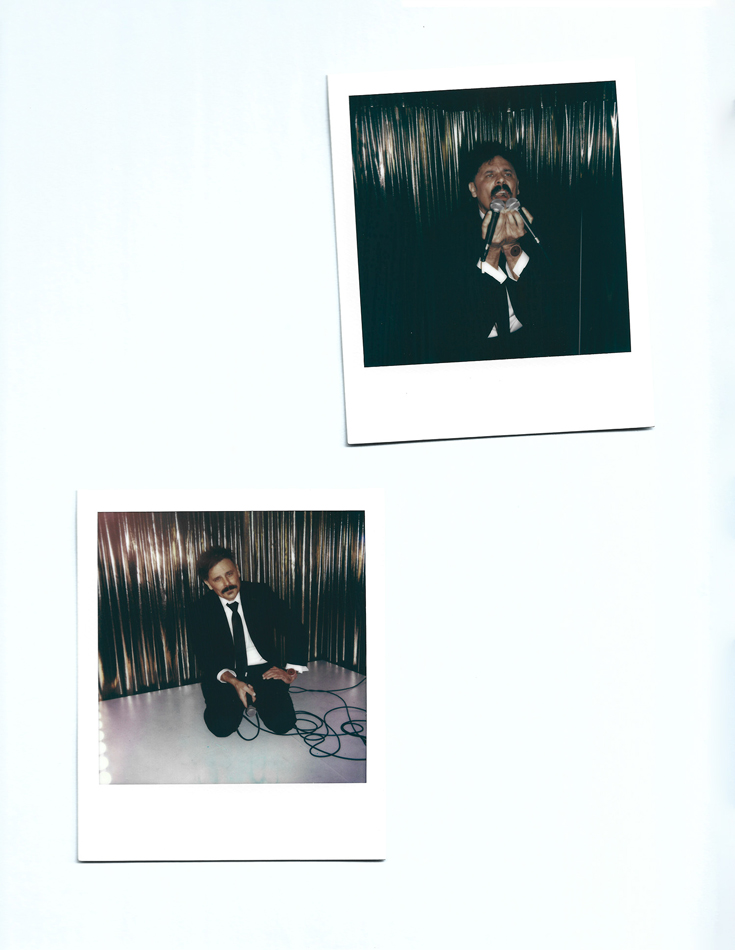

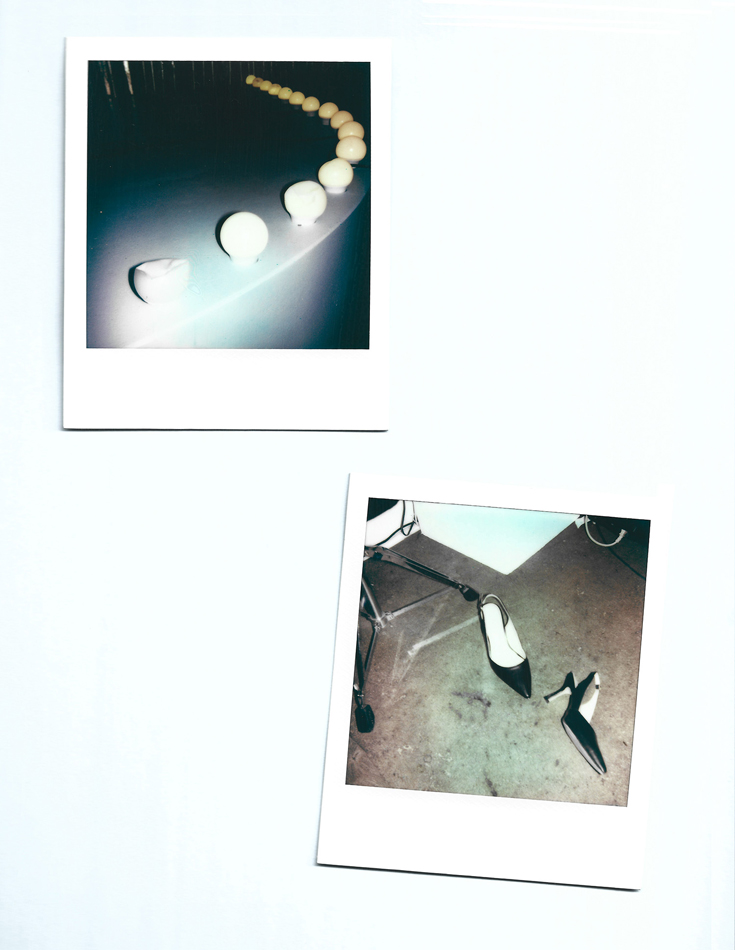

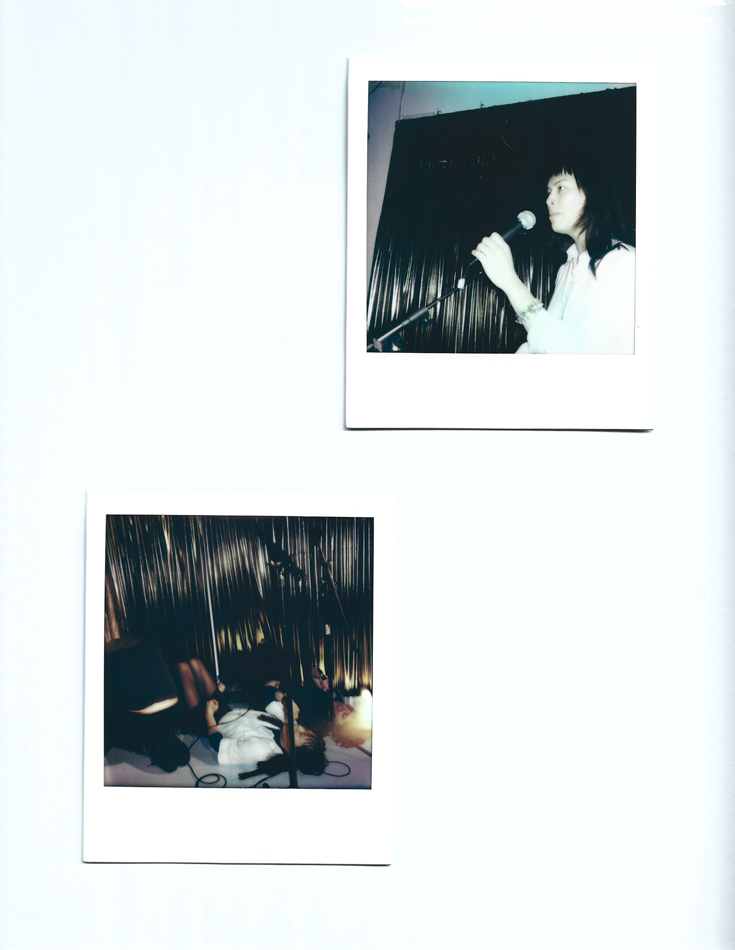

Joshua Ware belts tonight’s fare—Cyndi Lauper’s 1983 classic “Time After Time”—from a raised stage encircled by show lights. A digital timer counts down the hours, minutes, seconds. Tick, tick, tick. “Secrets stolen from deep inside / And the drum beats out of time.” Tick, tick. “If you fall, I will catch you, I will be waiting / Time after time.” Tick.

Geluda Gildar believes the possibilities inherent in karaoke far outweigh the risks. “Like so many people, I started off as a never-karaoke singer,” he explains. But a friend encouraged him to try it almost thirteen years ago. “It was such a rush and a thrill to confront this deep-seated fear of being seen in front of other people,” he says. Now the medium embodies for him a cleansing that undermines the (art) world’s “self-seriousness, towards vulnerability and towards a lack of criticality.” Instead, karaoke’s generative potency is about “how much you’ve committed to yourself in front of others,” he explains.

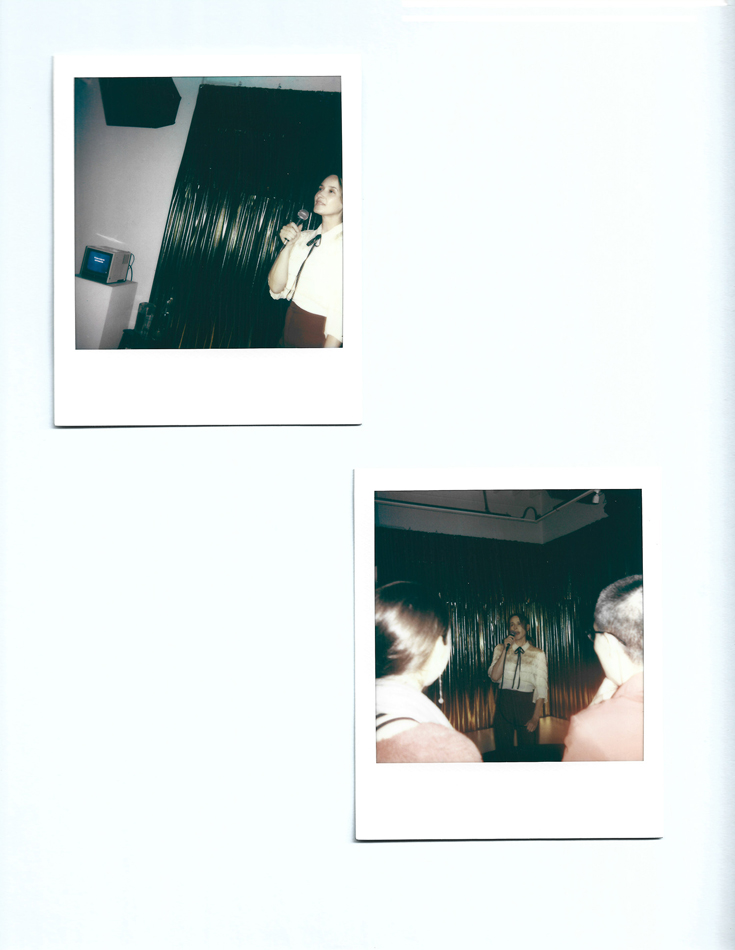

Elle Hong, an “antidisciplinary” artist in dance and other performance genres, agrees and expands her conception of karaoke to include its collective and self-determining powers. While “karaoke cannot be disentangled from work culture,” she says, referencing its popularity as a happy hour tradition around the world and especially in Japan, it has become a “socially acceptable” and “communal act of catharsis.”

Furthermore, it can be a safe place in which to explore and assert one’s identity, especially for trans folks. It’s a venue “where I get to publicly acknowledge that this is my voice,” Hong shares.

Karaoke can truly be a blast, but the vibe has to be right to induce me to pick up the microphone. And the vibes here are, as they say, immaculate. Right on Time and attendees alike enthusiastically take up the mantle and replicate Lauper’s lyrics afresh. Tick.

One singer assumes a low, metallic growl before Hong comes up to twist and roll around the stage, still managing to nail the vocals. Tick.

Another participant mimics puppet-like high pitches and later someone sings upstage center, sitting with their back to the audience. Tick.

Ben Coleman splits his time between the stage and the A/V booth in back, cheering on each repetition. Tick.

Attendees hum along while wandering in and out of LMP’s walls to grab a beer or a Time After Time-themed cocktail sprigged with thyme. Tick.

I duet with Geluda Gildar, and we improvise choreography, echoes, and beats, even though my voice shakes. Tick.

Curious and unsuspecting bargoers peek through the curtain, pulled in by the magnetic pulse of the room. Tick, tick, tick, tick.

The Right on Time collective evolved out of a mutual love for this interactive entertainment, and Geluda Gildar invited members in part because of their connections to Denver’s bustling karaoke scene. “We’ve used karaoke as a way to connect with other people, especially in the post-pandemic world,” says Laura Shill, who also links the medium and Time After Time to a shared desire to make artistic practices “more engaging, more immediate.”

Everyone’s energy swells as the timer runs out. On the last reprise, the Right on Time invite us to turn towards the lyrics and join in the chorus. We croon together gleefully, joyously. I’m having fun, which strikes me paradoxically as the most transgressive part of the entire experience.

“I get really nervous before I take the stage,” admits Shill. But committing to the bit feels “amazing,” which reflects Shill’s performance practice as a whole: “seeking out that humiliation, because what’s on the other side of it feels like invincibility… so after that shame burns off, you’re good to go.”

But Time After Time takes this abasement-seeking and alchemizes it with what Hong calls “karaoke survival” to produce new worlds. While opening night yielded a particular stratum in the work’s layers, each night assumes distinct characteristics depending on the song performed, the number and participation of attendees, the day of the week, and so on. Time doesn’t pass in the same way each night. Performing in a full room naturally feels different than an empty one. And observing “how the body copes with being in different situations,” as Hong says, is as much the point as “what arises out of the situation or the worlds that you build.”

More than a few folks (in Denver) have mentioned to me their desire to create without deliverables in mind or certainty about where their work will take them.

Performance art so often demands solemnity, or at least reverence, as a means to capture or educate ourselves on the lived experience—a feeling that pervades the art field generally. And while this reflective social contract may seem essential to art, it can be transformative to “have space to feel” (as Tomiello describes) without restraint. “We do have the agency to access joy through our bodies,” says Shill, “and that it gets amplified when we share it with others, and that it brings us into deep communion with each other to share joy and share vulnerable exchange.”

So though it may be naive to say that Time After Time is simply “an excellent use of free will”—an Internet phrase delighting in the diverting activities people do for the thrill of them—the thought also embraces an energy I’ve noticed lately in Denver’s art circles. More than a few folks have mentioned to me their desire to create without deliverables in mind or certainty about where their work will take them. And as Shill reminds me, “the practice is the thing.”

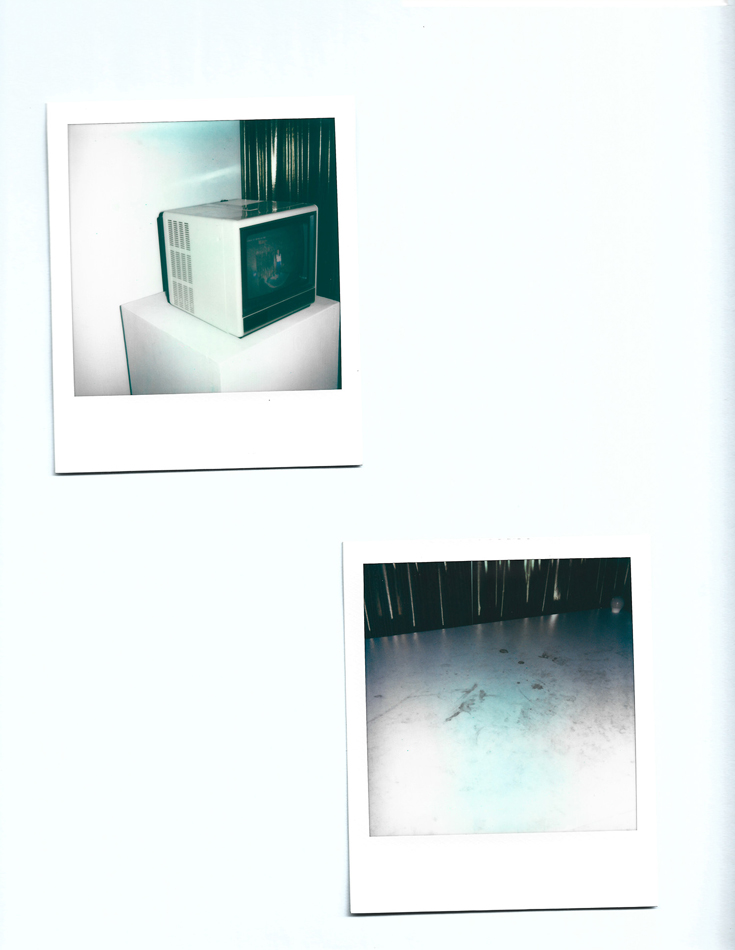

Reviewing the ephemera left in the exhibition’s slowly cresting wake, I’m convinced that it is Time After Time’s immediacy and absurd strictness that offer the most freedom. As “lo-fi static snapshots of a time-based experience,” Geluda Gildar’s Polaroids (like their associated and stringently-crafted performances) force attendees into forming their takeaways from the work. That product is “unreliable” chaos, deliverables be damned.

Much like the medium of karaoke itself, which Geluda Gilder says relies “on the predetermined form of the original music,” Time After Time isn’t so much about originality. “This meaningful looping experience comes back around in (the work’s) premise, where we are all repeating ourselves and others, with slight variation,” Geluda Gildar continues. “Even if the quality of the playback is low, like in karaoke, a deepening of experience can occur with each pass.” The exhibition’s sophistication therefore lies in its repetition. With a mantra-like ritual that pushes past boredom into familiarity, Time After Time illustrates how good art is not about knowing but about finding out.

Forthcoming performances of Time After Time are on January 10, 15, and 18, 2025, from 4:33 to 9:06 pm.