Labor: Motherhood and Art in 2020

February 28–May 28, 2020

New Mexico State University Art Museum, Las Cruces

A friend wrote to me after my child was born: “Pregnancy is like the movie The Fly—your body is transformed; giving birth is like Alien (the chest-burster scene); family life is like The Shining.” In every good horror movie, there is a moment of recognition, of profound transformation, and of transcendence, for better or worse. She was joking, but motherhood really is a little like that.

As a mother, I’d been looking forward to Labor: Motherhood and Art in 2020 in NMSU’s new art building, Devasthali Hall. Curated by Marisa Sage and Laurel Nakadate, the exhibition fills its elegant spaces with imposing artwork, mostly photographs and installation work. I was trapped at the start of the exhibition by the magnetic pull of four powerful pieces near the door: Mary Kelly’s Antepartum (1973), a grainy video of the movements of her distended pregnant belly; Catherine Opie’s majestic photograph of herself nursing her baby with the word “Pervert” scarified across her chest; Laurie Simmons’s loving portrait of her transgender child wearing a painted-on suit, Some New: Grace (Orange) (2018); and Maria Berrio’s Virgin and Child (2014), a kaleidoscopic mixed-media collage.

Moving further into the exhibition, it seemed that there was an aspirational quality to the works in Labor—that the artists explicitly wanted to show that a family is not an impediment to art-making but rather a fruitful source of creativity. In practice, artists can incorporate their children into their art, as subjects or collaborators. On the other end—the receiving end, as it were—there are a number of photographs of the artists’ colorful, difficult mothers. All of this is interesting to look at and well done, but what if the mothers’ vow to love and protect their children is directly opposed to the work they feel they must do? Is it possible that this is the case more often than not? What if the artists don’t want to include their children, or perhaps the children do not want to be included? In the art world, it is almost taboo to have a child. Many women artists choose to remain single and childless, as do some male artists. Perhaps because of the quantity of photographs in the show, viewers rarely get a sense of what motherhood means to the artists’ inner lives, how they have reflected on its difficulty and complexity. The work in this show, for the most part, doesn’t give a sense of art as a life distilled, truth told “slant” in Emily Dickinson’s words.

A case in point is Mother’s Day (2019), an installation by Lenka Clayton. Eighty-one women, all artists/mothers, were asked to record the same day: July 15, 2019. The resulting entries of what they did have been gathered into a book and the pages placed side by side. Reading some of these pages, their mind-boggling record of drudgery, induced a sense of visceral dislike towards the piece, perhaps because it reminded me of my own journal entries. It was easy to turn away from, though the drudgery is necessary; without it, and the love that fuels it, there are no transcendent moments to give meaning to life. I’m not sure what I am to take away from this installation—that parenting is hard work? Maybe it needs to be given a framework, so that viewers will be able to engage with it more meaningfully.

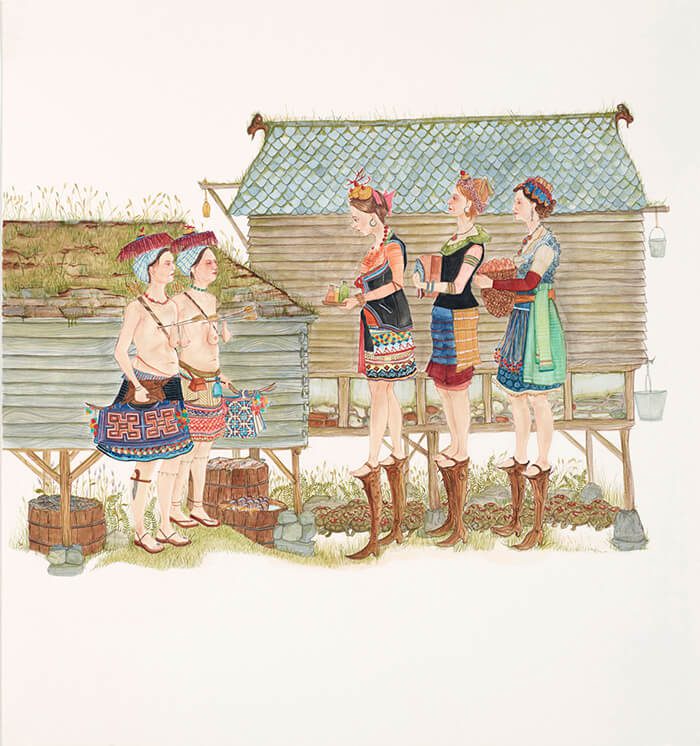

In contrast to the rest of the exhibition, two works by Amy Cutler, modest in scale, in non-bombastic gouache, painted with a nervous, precise hand, Remedy (2014) and Stampede (2013), use Western movie references to grapple with the discomforting feelings that go with motherhood, giving the viewer a sense of the artist’s internal alienation.

There are multiple events occurring in association with Labor, one of which is an exhibition at Casa Otro, A Path Described by a Body. It features eleven New Mexico artists and offers a more intimate exploration of motherhood, the other side of the large-scale, ambitious pieces in the NMSU show. The work is just as interesting as the museum show but on a smaller scale. Artist Stephanie Lerma has a pink knitted fiber sculpture on the wall in the show, its many breasts, complete with nipples, reminiscent of an ancient Middle Eastern goddess. The day I was there, a number of small children were drawn to the sculpture to gravely pinch the nipples. I admired their utter concentration, and their freedom to interact with the sculpture, in a way I wouldn’t have noticed before I became a mother. Not everybody is or needs to be a mother, but everybody has a mother. These exhibitions put a spotlight on the idea of motherhood as a powerful but almost invisible force in life.