Nevada artist Jung Min rejects the societal ideals of beauty, identity, and neatness—instead, she finds beauty in the grotesque.

Kaksi is a masked character in traditional Korean performances representing brides as rosy, quiet, and devoted. For the Nevada-based artist Jung Min, who goes by MJ with her friends, Kaksi is a censor. Whatever modesty, respect, beauty, and obligation this character celebrates and enforces, MJ rejects. For her, true self squirms behind any mask: irreverent, messy, blue, full of frustration, dread, and existential hunger.

A counterexample to Kaksi emerges in Masaki Kobayashi’s film Kwaidan (1964). In the film’s fable-like first segment “The Black Hair,” a poor Japanese swordsman leaves his wife, a weaver. She begs him not to go, says she will work harder than before, slaving for a better life. He hits her with the butt of his sword and goes off to marry into a wealthy family.

Remarried, though, he misses his first wife. And his second wife can see through him: she knows he remarried only for money. So, in time, he returns to his first wife, admits he is a fool, and asks for her forgiveness. Without showing any anger, she takes him back, says she is not worthy of his love, and blames his cruelty on poverty. He says they’ll be together from now on—for lifetimes—and strokes her long hair. The reunited couple gets into bed together, but in the morning the woman is gone. All that remains of her is a skull and a bizarrely heaving mass of hair. The man tries to run, but the hair pursues him. An unlikely but effective avenger, the enraged hair flies through the air and attacks, preventing the man from retreating.

I am reminded of Marina Abramovic’s performance Art must be Beautiful, Artist must be Beautiful from 1975 where Abramovic is armed with a brush in one hand and a comb in the other. She aggressively attacks her hair, roughly pulling the so-called beauty implements through it and repeating the blanket command, “Art must be beautiful, artist must be beautiful.” The repeated action is an angry rebuke and a calculated demonstration of the danger in pursuing shallow beauty. Like the black hair in Kwaidan, Abramovic’s hair becomes a character. It doesn’t want to be aestheticized or lay quiet. It is outraged.

From an early age, growing up in Korea, MJ refused to be docile, accept established thinking, or conform to ridiculous beauty and behavior restrictions imposed on women. In a recent video call, MJ broke down the gendered and national terms of her personal history for me. She insisted, “I don’t want to be the submissive girl,” and “I’m not going to try to impress Korean boys or change myself to try to fit into Korean culture.”

MJ is covered in tattoos. She has a devilish, sometimes raunchy sense of humor. She likes to interrogate taboos, and unlike most people, she often says exactly what’s on her mind. Like the best people, she loves to eat. Searching for alternatives to Korean culture, she moved to the United States where she thought she would belong. But, she found the U.S. uptight, consumed with orthodoxies, omissions, and violence. In the U.S., she still feels like she’s nationless, like she doesn’t fit in. “I’m always in this middle ground,” she explains, “I don’t belong anywhere.”

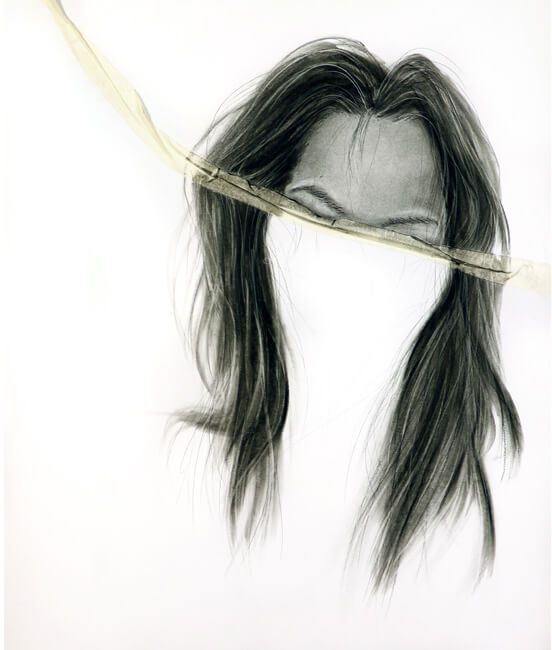

Yet, MJ doesn’t necessarily think exclusively about her identity when she’s at work in the studio. Recent works also address the shift in perception and emphasis on contemplative inquiry brought on by the pandemic. Works on paper are dreamlike and exaggerated, combining human hair and masking tape with charcoal or ink. MJ calls them bodyscapes. They might be hairscapes, too. In The Beauty of Emptiness (2020), a strip of standard-issue, general-purpose masking tape suggests the straps and the top edge of a kind of mask or blindfold interrupting a charcoal drawing of a woman’s face and hair. The otherwise sticky straps of the would-be face-covering seem to float untied next to the woman’s forehead, eyebrows, and on top of her thick, shoulder-length hair. The blank space of the lower half of her face feels strangely loaded, impossibly thick, perhaps referencing a suffocating material or condition. True to its name and intended function, the tape covers. It masks. But, something is wrong. Where is the tape coming from? Who or what controls it and why? The beauty and emptiness extolled in the title don’t feel entirely positive when they hit the page.

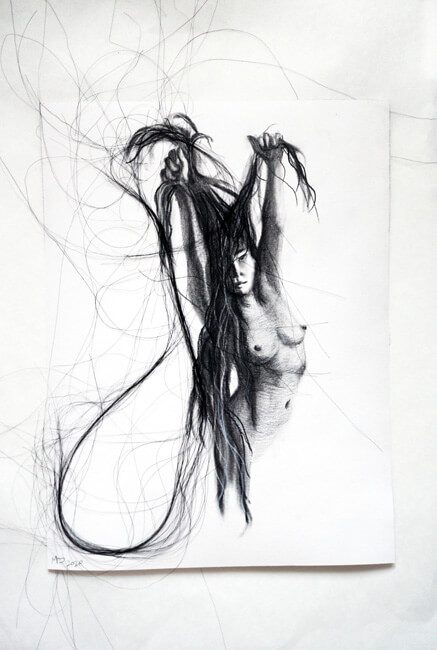

Throughout MJ’s body of work are nude self-portraits in which she extends, emerges from, or immerses herself in massive snaggles of long, black hair. In some instances, she appears to wring it out and yank it. In these works, she has come out from behind the Kaksi mask. Her hair is like “The Black Hair” or Abramovic’s hair. It covers her eyes, her face, drapes down over her torso, her legs, and passes her feet. Tangled with hair, MJ becomes as twisted as it is. Hair consumes her within an outlandish, seemingly endless enormity. It weighs down her head. In waves, it extends and extends.

“My philosophy is that we have to go through this. Right now,” she says, “everything is colliding. Everything is exposed. This has to happen in order to find a balance eventually. For me, I have to understand I am always going to be uncomfortable, not fit in perfectly. However, I need to find beauty.

Sometimes in her work, we see MJ stretch out her arms and decisively, triumphantly extend full fists of hair as far as they will go. In these cases, hair is strength, like Samson’s hair of Biblical lore. MJ’s hair is her lion’s mane and her declaration of power. As she intertwines with it, loops of hair also spin and twirl all around her as if they are special limbs dancing at her command.

A series of five small self-portraits from 2020 titled Tensions and Lines incorporate charcoal and hair. The hair is at least twice as long as the figure. In some cases, it’s longer. One of the pieces shows a double figure. The upper bodies of two hairy figures have sprouted from a shared waist. In another, the figure crouches down, her head covered and surrounded by a dramatic hairscape that seems to move as if she controls it with some kind of mind power. In another, her arms are raised up, her hips are thrust back, her chest forward. The figure is a triumphant dancer at the end of a rousing routine. Her arms and hands are extended and enlarged. They have gotten stronger and grown larger from winning a struggle.

MJ describes the comfort she feels with some coarseness and distortion, “I’m not attracted to elegant women. I’m attracted to the grotesque body.” She elaborates further on her sense that the world, in general, is in transition. She acknowledges that fear comes with any transition but underscores that the change, however gnarly, is necessary and a long time coming. “My philosophy is that we have to go through this. Right now,” she says, “everything is colliding. Everything is exposed. This has to happen in order to find a balance eventually. For me, I have to understand I am always going to be uncomfortable, not fit in perfectly. However, I need to find beauty. I find beauty in contorted bodies. I find beauty in hair. I feel like that’s what people need to do now too. Right now, so many things are colliding, and so many things are exposed. Ugly things are exposed. You have to find beauty, regardless.”

I ask MJ what kind of music she listens to in her studio. She says that when she is feeling good, she listens to Buddy Guy. I put on Buddy Guy and imagine MJ in her studio, feeling good, facing a blank piece of paper, charcoal or brush in hand, surrounded by the photographic studies she makes of her hair and body. I hear Buddy Guy lamenting his mistreatment, a horrible job, the times when he got knocked around or shut out of the places he wanted to go. I imagine his guitar riffs scoring MJ’s action as she marks the paper, hashing out the contours of a thigh, the bridge of a nose, or at the moment she starts to render masses of hair engulfing her. “Damn right, I’ve got the blues,” Guy sings, “I’ve got them from my head right down to my shoes.”